Photo credit: Meryl Schenker Photography

On Tuesday, March 11, 2025, a packed house listened as former SCJS Cole Fellow, Dr. Daniel Heller moderated a conversation between current faculty Dr. Gilah Kletenik and Dr. Devin E. Naar. The conversation touched on the origins of Jewish Studies programs in Europe and the U.S., offering some historical perspective for helping to interpret today’s challenges. Gilah and Devin also shared their personal experiences teaching Jewish Studies in our current climate before concluding the talk with a discussion about the role Jewish Studies plays on campus today. Want to hear more? An audio recording and transcript of the full talk can be found below.

On Tuesday, March 11, 2025, a packed house listened as former SCJS Cole Fellow, Dr. Daniel Heller moderated a conversation between current faculty Dr. Gilah Kletenik and Dr. Devin E. Naar. The conversation touched on the origins of Jewish Studies programs in Europe and the U.S., offering some historical perspective for helping to interpret today’s challenges. Gilah and Devin also shared their personal experiences teaching Jewish Studies in our current climate before concluding the talk with a discussion about the role Jewish Studies plays on campus today. Want to hear more? An audio recording and transcript of the full talk can be found below.

News coverage

On March 13, 2025, Seattle Times journalist Nina Shapiro sat down with UW Stroum Center faculty Devin E. Naar and Gilah Kletenik to discuss their talk, the current campus climate, and more. Read the Seattle Times article.

Audio recording

Edited transcript

*Transcript has been edited for clarity and length*

What can the history of Jewish Studies tell us about the challenges of today?

Telling a different narrative

Daniel Heller: From your vantage points, what do you think the history of Jewish studies might be able to tell us about the challenges that we are facing today? Are there any lessons that we can learn from the generations before us that worked so hard to establish this field of inquiry?

Gilah Kletenik: I actually think that’s a great question with which to start our conversation, because I find that too often the history of Jewish studies is absent in our conversations about what’s happening today. Jewish Studies really begins in Germany in the 1810s and the 1820s, when a group of German Jewish intellectuals, mostly at the time just students at the University of Berlin, wanted to tell a different story. They realized that the study of the Jewish past, of Jewish ideas and Jewish history was dominated by historians and theologians who were working from the Protestant tradition, and they felt that not only were Jewish ideas marginalized, but that Jews themselves were not in a position to tell their own stories.

In fact, there were no Jews at any German university teaching Jewish ideas or Jewish texts.

All of what was being taught by Protestant historians, theologians, and philosophers. What really pushed them over the edge was the climate in Germany at the time. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, there was a huge surge in nationalism. And that type of nationalism, as we know, often leads to different forms of antisemitism. These Jews felt like they had to do something, and particularly they were driven by the desire to push for Jewish emancipation, Jewish rights and Jewish acceptance, both legally and socially and culturally. They were living in a society that was not just predominantly Christian, but Christian supremacist, by which I mean, every part of life in Germany at that time was built to promote and accommodate people who were Christian from the moment they were born, until the moment they died. This was an entire legal, cultural, social system that promoted Christianity and by default, therefore, excluded minorities. And because of the role that Jews play in the history of Christianity, that placed Jews in a particularly precarious position. So that’s the background of Wissenschaft des Judentums, the scientific or scholarly study of Judaism. I want to make two important points that I think are relevant for our moment.

The first is that these scholars did tremendous work to which we in the field of Jewish Studies are still indebted. They told a different story when it came to the Jewish past especially Second Temple Judaism. They show that rabbinic literature, that Jewish contributions to literature and the culture did not stop with the Hebrew Bible.They said, you know what? Christians love to focus on the Hebrew Bible, take it and supersede it. We’re going to show them a whole wealth of Jewish knowledge, Jewish ideas, Jewish culture and text that comes after the rise of Christianity. So they focused on Second Temple Judaism, rabbinic literature, medieval Jewish philosophy, Kabbalah, and lots of manuscripts. They did really important pioneering work.

The second point that I think is really relevant is that their work, notwithstanding its scholarly merits, was very ideological. They were not disinterested. They wanted Jews to talk for themselves. They were intentionally appropriating the kinds of imperialistic, nationalistic methodologies that were being employed across the Academy at the time and said, let’s, let’s flip the script. Let’s show the role that Jews have played in making our society. And so they developed a counter-narrative, that some scholars have called a pushback of the colonized or the oppressed. They look at these Jewish scholars as one of the first minorities to say, let’s tell our own stories and let’s tell our own history.

What I find relevant for our moment is this legacy of Jewish Studies, to tell a different narrative, resist or critique or show the ways in which the dominant methodologies, the dominant ideals, or to underscore who they are excluding. What I try to teach in the classroom is how Jewish studies can allow us to think otherwise, how it exposes us to different texts, different ideas, different ways of thinking that allow us to denaturalize and deparochialize what we have taken for granted. It allows us to think otherwise. And in our moment, my hope is that Jewish Studies can really continue to do the important work of critique and resistance.

If we go back into the history of Jewish Studies at the university here in the United States, we also arrive at a point of very intense political contestation.

University quotas and the beginning of Jewish and Sephardic Studies

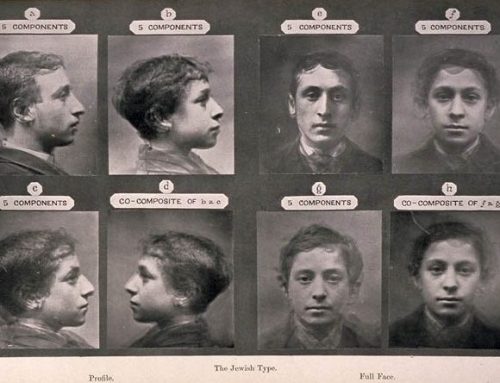

Devin Naar: We arrive in the 1920s, and we arrive at one of the universities that is in the headlines 100 years later, and that’s Columbia University. Columbia University was among the elite universities of the time that in the 1920s was instituting quotas against Jewish students [and] trying to exclude Jews from academia. And they also introduced another aspect of the university culture, which is the legacy program. In other words, prioritizing admission for people whose parents had gone to the university. This was a more sophisticated way of saying, let’s not let Jews, immigrant Jews and their children, into the university.

It’s in that exact moment of the 1920s, in 1929, 1930, that Columbia University — even though there’s all this anti-Jewish sentiment going around on campus — accepts a private donation from a member of the Jewish community to establish the first chair of Jewish history at an American university. And they brought in a very well-known scholar who had essentially found the field of modern Jewish history and Jewish studies, more generally.

Salo Baron, who is my advisor’s advisor’s advisor. And also Dan’s advisor, and many of the other people here are part of that “family tree” of sorts. Now, what was the purpose of establishing Jewish studies? It was in continuity with some of the things that Gilah was saying, trying to make Jews and Judaism acceptable. And maybe through education, we could bring into understanding among a new up-and-coming generation of the American elite, at Columbia University, that Jews are like the rest of us, that Judaism and Jewish culture and Jewish history can be studied.

And it can be interrogated, investigated, just like any other topic or people and considered like any other people, any other community. So it was sort of ensconced in a kind of respectability politics: make Jews appear that they belong in American society. Now, that had a certain number of benefits, because while Jewish Studies entered the curriculum in a certain sense, in Jewish history in particular, it also had its limits in terms of trying to present a presentable image of the Jews. And there were certain kinds of Jews and certain Jewish stories that were not part of the story from the beginning.

When Jews from the Ottoman Empire arrived [in the US] and some of them found themselves at Columbia University, they tried to find a space for Sephardic Studies at Columbia University. And what’s interesting is that Jews coming from the Muslim world, Jews who were not quite European, maybe they were more “Oriental” in the language of the time –were they white or were they brown? Were they “civilized” or were they barbarians? — did not readily have an embrace from the Jewish Studies enterprise at Columbia University. In fact, the first Sephardic Studies program in the entire country was also established at Columbia University in the 1930s, but under the auspices of Hispanic Studies.

Why is that? Because Sephardic Jews didn’t have anything to offer this [Jewish] narrative of respectability politics and integration in that way. But they had what to offer to Hispanic studies, because there was a sense that Sephardic Jews who preserved the Ladino language preserved the language of Cervantes. So you go and encounter a Sephardic Jew, and you can hear a living museum of the Spanish Golden Age. So it [Sephardic culture] did something for Hispanic studies in a way that it didn’t, for Jewish studies, in general. And that’s sort of the beginnings of Jewish studies in a very conflictual moment.

What are the challenges Jewish Studies faces today?

Daniel Heller: I’m going to push you both a little bit and stress test these ideas, and I want to push you a little bit more to think about how what you’ve just described speaks to the challenges that we face today.

Accomplice to genocide or self hating Jews?

Devin Naar: I think the expectation of hope sits for me in tension with how I see the way in which Jewish Studies is viewed on this campus and across the country, and the way that I see it. I feel like on the one hand, Jewish Studies is accused of being an accomplice to the genocide of the Palestinians in Gaza. This is like one narrative that is flung in our direction. And then, on the other hand, there’s a narrative about Jewish Studies that Jewish Studies is comprised of a bunch of self-hating, anti-Semitic, anti-Zionists.

Those two things are a little bit mutually exclusive, I would say. And so in a certain sense, I feel like the “Jewish Question” is coming on to the heads of Jewish Studies right now in this moment, like: “What is the place of Jews in society in general?”, is [a question] being asked of Jewish Studies as a kind of disciplinary university enterprise, as if almost different political factions are, projecting onto Jewish Studies or scapegoating Jewish Studies. If only Jewish Studies would change, if only Jewish studies would do something differently, then X would be the case or Y would be the case, then Israel would be safe, or that the grief of the Palestinians would be stunted and resolved.

What is really relevant, I think, to our current moment, is the dynamic that he [Yosef Hayyim Yerushalmi in his book, Zakhor] sets up between Jewish history and Jewish memory.We might think that these two ideas are in consonance with each other — Jewish history and Jewish memory — [that] they’re mutually reinforcing, but [the book] actually sets it up as a kind of tension. That Jewish memory, the way that a Jew, the way the Jewish community in a collective sense, transmits an understanding of their past which is oftentimes very selective and done to advance a very particular identity, very particular understanding of how Jews are and should be in the world, is in tension with Jewish history, which is based on rigorous and critical investigation into the past.

You might find that the narrative, the received narrative that is repeated and told in popular form, does not necessarily stand up or comes to be challenged once you begin to investigate.

Once you go to the archive, once you go to the historical records, you begin to see a different kind of narrative that can emerge, one that may be in tension. And so for me, what’s really interesting when you think about Zakhor, here on the back of the book, he’s described as an exemplary “Jewish historian of the Jews.” So this goes back to Gilah’s point also that Jews are beginning to develop their own narrative.

But the communal narrative and the historical narrative are in tension, and this is a tension that we see now on display very profoundly. Like this is the idea that Jews {in Jewish Studies] are against the Jewish people. Jewish Studies is against the Jewish people, which I don’t endorse that view. But there is this sense of distance and tension between the received narrative of Jewish identity and Jewish memory, and the critical investigation that comes with Jewish scholarship. And I think that’s a really key point for us to take into today’s understanding of some of these tensions.

And I would like to just mention how I arrived at coming to Zakhor, because it is where memory and history come into conflict, I was involved in a Holocaust commemoration program at the local Jewish Federation in the city where I was a student. And, I was going to be representing the student body and lighting a candle. Before the program, one of the organizers comes to me and says: what’s my relationship to the Holocaust? And I explained, well, my grandfather’s brother and his wife and children were murdered in Auschwitz. And she says, Where was your family from? And I said, Salonica, Greece. She paused. She said,“That can’t be. I’m a survivor of Auschwitz, and I never met a Jew from Greece.” And that was really shocking to me. But I think it reveals somehow the limits of the collective narrative. The European-centered nature of the story. And that’s what led me to the Jewish Studies department at my university.

What is the appropriate role for Jewish Studies in the classroom?

Daniel Heller: Both of you spoke about the ways in which these early Jewish studies scholars viewed their scholarship in a way, as a form of activism. This is one of the arguments that is often spoken about or used against Jewish studies in this present moment. That is to say, I’ve certainly heard the arguments made in Melbourne, Australia, that scholars should not be political activists. They’re using our classrooms to ideologically indoctrinate our students, to twist their minds. I mean, I have to be honest, if I can get my students to read five pages, that’s extraordinary in and of itself. So I love the idea that they think I can, you know… But in any event… So, I’m just wondering… this is going to bring us to this question of teaching and in the classroom.

Do we bring our full selves? Do we view our classroom as a place to promote our own political views at the expense of others? As a Jewish Studies scholar, how do you both approach that question? Maybe philosophically, but also in the in the nuts and bolts of the classroom teaching that you do.

Christianity defined academic neutrality

Gilah Kletenik: Okay, that’s not an easy question, but in order to get to answering that, I actually do want to talk a little bit more, build off of some of what Devin said about the field of Jewish Studies and also my own position within it as somebody who works in philosophy and Jewish philosophy.

We are at a moment now where there are Jewish Studies departments and centers across universities here in the United States, and something that I think is often overlooked because the modern university prides itself on a kind of objectivity, neutrality, and scientific pursuits, that actually the American University is still indebted to the Christian supremacy of European universities. That’s not just because many universities here in the United States were founded as Christian seminaries like Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Princeton, and others. But also the disciplinary boundaries themselves are inherited from the European Christian university, which goes back to medieval times. Now, why is this relevant?

Take, for example, the field of philosophy. Now, generally speaking, when somebody thinks of studying philosophy in a university here in the United States, they are thinking about certain philosophers who are part of a particular canon. If they’re thinking about early modern philosophy, or modern philosophy they’re thinking about Descartes or Kant or Hegel, and if they’re thinking about contemporary Anglo analytic philosophy, even if they’re not directly studying these major figures, they’re indebted to the ways of thinking that was propagated by these early modern and modern thinkers. Now, the problem is that philosophy here in the so-called “West” is predominantly Christian philosophy, and its origins in medieval times were constructed on the active banning and censorship of medieval Jewish and Islamic philosophy.

In 1277, the Bishop Tempier banned what they called “radical Aristotelianism,” which banned many forms of medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophy.

This matters because it literally censored entire libraries of thought, which led to the dominance of a very specific Christian approach to what it means to do philosophy and who counts. And we still see this today in two significant ways. First, suppressing what they called radical Aristotelianism, they suppressed the political nature of Islamic and Jewish philosophy that saw itself first and foremost as engaged in politics and ethics.

And second, they were suppressing alternatives to Christian dualism, which sees the mind, reason, or soul as transcending the body. This censored an entire school of philosophy that actually looked at reason as embodied, people as situated in time and place, all thinking as always existing in time and place.

This matters because the Western and liberal notion of disinterested thinking, of “neutrality” and of “objectivity” traces itself back to Augustinian Christian thought from the fourth century that excluded more materialist approaches to what it means to think, and that all thinking is always already embodied in time and place, and therefore politically and ethically oriented.

This erasure of Islamic and Jewish philosophy has led to a very particular approach to what it means to think and what it means to think as “disinterested.”

And so to your question about advocacy, I would say that the presupposition that advocacy is a problem or the notion that we could ever be completely objective or completely disinterested is an inheritance from Augustinian, Cartesian, Kantian philosophy, which is Christian.

So that’s the first point I want to say. I think, it’s true that the early founders of the field of Jewish studies were very ideological. And they were open about this and they didn’t really have a choice. They did not have rights. And they saw this as a way to basically say, we deserve rights.

We deserve legal rights, social, cultural rights. And our way to do that is to show that Jews matter, that Jews are not the dead letter, that Jews have contributed to civilization well after the birth of Christianity. And so that is how I think about this question. I’m coming out of a Jewish philosophical tradition that contests the presupposition that we could ever be fully disinterested. Now what does this look like in the classroom? Well, I wish I could get my students to think one thing or that. I wish everybody would walk out of class and be like, oh, I agree with everything that was said. And, that’s not going to happen.

What I take from the founding of Jewish Studies is their ability to critique the hegemonic, dominant ways of telling history or looking at ideas. And it’s this practice of critique that I try to train my students to practice.

Avoid Godwin’s law: define all slogans and buzzwords

Devin Naar: [In my seminar on antisemitism in the spring of 2024] we had a student who had been a fellow at the ADL. We had a student who was co-organizing the encampment. So we had a wide range of participants in the class. We spent two hours, for example, debating whether or not to put a hyphen in antisemitism, and what that means, what are the possible meanings, the ideological implications of putting a hyphen. So what the class became was a space to slow it down.

And I think for me that was the most important thing because, the classroom is not the quad and the classroom is not social media. This was tested very early on when a student compared the Seattle Police Department to the Nazis.

Another student looked at me like, Hello? You’re going to do something? So I said, You know–I didn’t have, like, a plan–so I said, I think we’re not going to be making these kinds of comparisons and explained to them Godwin’s Law. I don’t know if you know Godwin’s Law. Godwin’s Law is a social media adage that the longer a conversation develops, the more likely you are to denounce your opponent as Hitler or the Nazis and it approaches one — it eventually will happen — the purpose of which is to shut down the conversation. So I said, We’re not going to make Nazi analogies. I went home; I couldn’t sleep.

Because I felt like I had just imposed a speech code on my students.

So I came back to the next class and I said, We’re not going to have the speech code, [and] you can say whatever you want. But you have to explain what you mean by the term “Nazis.” Is the Seattle Police Department bringing civilians to gas chambers and concentration camps?

No. Okay, well, what do you mean when you say this? And I applied this to all of the “buzzwords.” Zionist. What does that mean? Anti-Zionist. What does that mean?

“From the River to the Sea.” You can say it, but you’ve got to tell me what you mean by it.

“Israel is a Jewish and democratic state”. I consider this also in the realm of slogans.

What do you mean by that? And this [approach] enabled the students to delve not only into the readings, but also to become a little bit vulnerable and to develop this sense of community that I think was not dependent upon any particular ideological position. Obviously I agree I’m a political being. We all are, as Gilah was saying, but it forced them to begin to articulate their own ideas and to move beyond the slogans. And I think that was a great benefit and something that added in the classroom. And it also had a dramatic impact on the morale of the students because they began to develop community with people that I don’t think they would ever speak to in another context, but they were in that classroom together because they wanted and were willing to investigate.

One day we had two Jewish students sit next to each other. One described themselves as an anti-Zionist wearing a keffiyeh. Another student was coming to class, often with Jewish symbols or Israeli symbols, like a big Star of David. They wound up sitting next to each other and they arrived early. I’m like, okay, what is going to happen now? And the one wearing the Star of David turned to the student wearing the keffiyeh and said, Why are you wearing that? The student wearing the keffiyeh began to explain why that person was wearing the keffiyeh. The other student was like, Oh great, now can you get me a keffiyeh? [laughter from audience] No, that was not what happened. But what did transpire was a moment of recognition of mutual humanity. And I think like, okay, this person wearing the symbol that I find scary is not against me necessarily. They explained the reasons–the political, the cultural, historical reasons–why that person felt as a Jewish person a sense of connection to and solidarity with Palestinians. And I think for me, that was a very, very important moment. And I think it begins to address what kinds of things happen in the classroom when you open it up and you make a space for delving into the materials in the classroom. And I think that’s what a lot of my colleagues do in Jewish Studies.

How to lead brave conversations

Daniel Heller: Let’s say a couple of things that I’m hearing, that I think are things that I actually see with the vast majority of my colleagues in the humanities, which is that you are modeling an expertise that is not built on knowing everything, and the way you view the world is how things should be.

In fact, you’re showing that part of what makes researchers experts is a sense of deep humility, and that if they come into a moment where they make a statement or a claim that doesn’t sit right with them, they have the courage to actually say, I’m going to learn from this, to share, and then to ask for support and to figure out opportunities to grow.

The second thing that you did in that room, which I think humanities scholars and educators, when they’re at their best do, is ask everyone to just slow it down and just to take a deep breath.

What a gift. What an incredible gift educators have at this university to have ten weeks to build relationships and to build trust with our students, to be able to have those brave conversations. And when I think about one of the important purposes of Jewish studies,I think that’s one of the first things I think about that structural gift we have just to have that time and that we can tell students don’t. You don’t have to choose a side. You don’t have to just be a position. The other thing you modeled in that moment is rather than having your students adopt a warriors mindset that they’re there to win, you’re telling them, actually, I’m here because you’re here because I want to help you understand the person sitting next to you and trying to understand how people arrive to their views oftentimes helps us. Fear them a little bit less and be open to understanding our common humanity. So for all those things, I applaud you and Gilah as well.

Jewish Studies beyond the classroom

Daniel Heller: So there are amazing things happening in your classrooms.

But like you said, the classroom isn’t the quad. But does that just mean that Jewish Studies has no role to play? I mean, if this is a public university, the quad is a public sphere.

Being a generous reader

Gilah Kletenik: Like I said, going back to what Jewish Studies is really about, reading texts with students or studying the Jewish past, I find in my experience, forces us to think otherwise. It forces students to reevaluate the ideas that they had taken for granted what they had thought they knew. Whether about reality, about themselves, about what it means to be a human. And for me, part of this is connected to the marginal status that Jewish Studies had, and arguably still has, today, especially in philosophy. UW is wonderful. And it’s great that I’m teaching a course in Jewish philosophy, but there is no dedicated position in the Philosophy department for Jewish philosophy, much as there is no dedicated position for somebody to study and teach Islamic philosophy. So I think that marginality of Jewish Studies and the thinkers from whom I draw, helps orient what I think Jewish Studies can offer, which is an ability to question our beliefs, our values, what we take for granted. And oftentimes in a Jewish Studies context, that means rethinking and critiquing the dominant and prevailing ideas of that particular moment.

And something else I really draw from Jewish Studies is the patience to read text closely and carefully, to sit with a text. There was a moment this term, when I interrupted our studying and spoke to the students about what it means to be a generous reader. Which means that we’re first trying to understand the text saying, what the author is trying to say. To at least understand what they are saying and the perspective they are trying to convey. And only once we understand where that’s coming from, can we then do the next level of assessing, evaluating and then making a judgment. I find this is a benefit of philosophical thinking in general, when students are forced to pause, read something closely, understand what’s being said and what the opposing position is, leads to far more fruitful conversations and critical thinking. And I think that is something that we offer. And in the humanities more broadly, particularly at this moment, we can teach critical thinking. We can offer this slow work of reading and being in conversation.

Defending democracy

Daniel Heller: I don’t know if anybody else felt this, but all of a sudden, when you describe the pain and the grief that comes from losing two students, two real people, who are part of our community, whose lives were lost, all of the positions, all the ideology just dissolves and something opens up just to be able to listen and to hear, and it’s something that you cultivate and that hopefully our Jewish Studies colleagues cultivate in the classroom all the time. Students have described our classes in Australia as a refuge.

And that’s how I like to think about the role that universities and university classrooms can play in this background of polarization. Yes, we’re there to get people to talk about difficult things. Yes, we’re there to get them to embrace tension, but we’re there to show them that not only is that not a scary and dangerous thing, it can also be joyous.

It can also be a pathway to discover common humanity, and it is the way that we practice democracy. And really the key commitment, I think, that Jewish Studies classes and educators can think about as they move forward here, that we are really defending democracy by practicing it in the classroom, by embracing that viewpoint diversity. I want to thank you both for your comments.

Do Jewish Studies classrooms provide “safe space” for objective histories about Palestine, along with the State of Israel?

So that’s the question as it was phrased. And I want us to address that question. But I first want to ask a question about meaning. And what do we mean by safety and by safe spaces?

What is a “safe space”?

Gilah Kletenik: Well, okay. What is a safe space? What does that mean? What does safety look like in the context of a classroom? There are a lot of views on what that is. The first thing is to say that when somebody says, no matter who they are, that they feel unsafe, we need to take them seriously. We need to recognize that that is an affect and a feeling, and trust that they’re sharing that from a place that is genuine for them.

Even if we might undergo the same experience and not feel unsafe. And so I think that’s the first thing that is incredibly important. In terms of the classroom, I think it means co-creating a space where students feel that they can share their opinion.

I often try to ask students sometimes, well, where does the text say what you’re saying? Or what part in this reading could you point to that is making you say this or making you wonder, or what is it specifically about what was said that is leading to your point? So I think that helps students, avoid or at least ground the conversation in something that deflects or can turn away from something that is particularly contentious.

But I do want to take a moment to talk about safety, even beyond the classroom, because we’re seeing a concern for Jewish safety, in the newspapers and in the headlines. I think, yes, we always need to take the concern of all students who don’t feel safe seriously, and that is a top priority. I also think we need to be, if Jewish history has taught us anything, more than a little skeptical when certain people say that they’re doing things in the name of Jewish safety, particularly when these people don’t have a record of being especially generous to Jews but actually have a record of antisemitism or sympathizing with antisemites, when they weaponize a concern for Jewish safety and it’s not coming from a place that is genuine, that actually makes all Jews unsafe.

And when Jews are instrumentalized and a disingenuous concern for Jewish safety is weaponized, that makes all Jews and all people unsafe. And I think we need to be careful about how that concern for that concern and what steps are they taking to ensure that safety?

Importance of discomfort in the classroom

Devin Naar: I would echo what Gilah said in terms of taking all articulations or expressions of an absence of safety very, very seriously, very, very seriously, and do everything that’s possible to alleviate those concerns and address them, if somebody lodges a complaint, you have to investigate. Must look into it. You have to look into it.

From my perspective, one of the challenges emerges when we think about the relationship between comfort and safety. And I feel like this is a kind of spectrum of things that people don’t necessarily like, from things that people dislike to “I am afraid for my physical safety.” And I think that discomfort in the classroom is necessary. If my students are not a little bit uncomfortable, I’m not doing my job. This is not about physical safety. This is about an intellectual discomfort, or a sense that I’m hearing things that I don’t necessarily agree with. Maybe I’m questioning them [the ideas or perspectives]. Maybe I don’t like them. Maybe I’m offended by them. That is all, for me, fair game, as long as it is done in a way that is not overtly threatening or violent or anything like that. I think one of the challenges that we have, is that some of these different categories of concern are being conflated. And harassment and violence — completely unacceptable.

On the other hand, discomfort is okay. And you know, you think about the history of Jewish studies and Jews on campuses. Jews feeling comfortable on campuses is only a 50 year-long thing. Before that, first of all, you’re not getting into the university. Or if you are getting into the university, you are definitely not comfortable there because you know that you applied and you got in there and many other people applied and they didn’t because of the Jewish quotas. So I think having that context in mind is a little bit helpful.

How is Jewish Studies implicated in the structures of whiteness?

Devin Naar: If we go back to the history that we were describing about the development of the university, what’s fascinating is the shift over time. So in the time of the quotas at the university, even white looking Jews were not considered white. I think that’s a very important element to imagine. And in that moment, Jews were generally trying to fit themselves into whiteness, saying, actually, We are white, we are American. We belong in these institutions. We belong in American society. We belong in the university.

What’s fascinating now is if we think about the dynamics today and how the question of Jewish racialization has shifted.

From one perspective, Ashkenazi Jews are white if they are perceived as white and treated as white. But also not all Ashkenazi Jews are white. There’s one question. Not all Jews are Ashkenazi is yet another element in the story here.

But what we see happening is actually a repudiation among some in the Jewish community today of their whiteness, or a distancing from whiteness, which becomes related to a claim that actually Jews are not European. Jews are Middle Eastern. Jews are from Israel. This is where we are from. And so I find that fascinating as a historical question that requires investigation and study.

If you go back 100 years ago, Jews were very much invested in trying to represent themselves as white. And now we have a different kind of [politics]. [Back then], if you would say Jews are Middle Eastern to an Ashkenazi Jew, they would say, no, no, that’s not me. That’s the ones that we didn’t let in. Those were the Sephardic Jews. But now you have a different dynamic that is in play, which is related to the broader political climate in which there are some Jewish organizations and Jewish institutions that are trying to make the argument that Jews are actually not white, that to call Jews white is actually a slur. I think that that is a historical question, that requires further investigation. But I think recognizing that shift is one starting point.

Dan Heller: Okay. Jews, we never quite fit into the right boxes, do we?

We’re messy. We’re really, really messy. Maybe that’s what Jewish Studies is all about.

To embrace that mess. To embrace that complexity. Right?

About Gilah, Devin, and Daniel

Gilah Kletenik is the Stroum Center’s 2024-2026 Hazel D. Cole Fellow in Jewish Studies. She is a scholar of philosophy, specializing in Jewish philosophy from the medieval through modern periods. Read more about Gilah’s teaching and scholarship.

Devin E. Naar is the Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies, Associate Professor of History, and faculty at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies in the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. Read more about Devin’s teaching and scholarship.

Devin E. Naar is the Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies, Associate Professor of History, and faculty at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies in the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. Read more about Devin’s teaching and scholarship.

Daniel Heller was the Stroum Center’s 2012-2013 Hazel D. Cole Fellow in Jewish Studies. Currently he is the Kronhill Senior Lecturer in East European Jewish History at Monash University’s Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation. Read more about Daniel’s teaching and scholarship.

Daniel Heller was the Stroum Center’s 2012-2013 Hazel D. Cole Fellow in Jewish Studies. Currently he is the Kronhill Senior Lecturer in East European Jewish History at Monash University’s Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation. Read more about Daniel’s teaching and scholarship.