By Denise Grollmus

When Joe Butwin began his graduate studies at Harvard in 1965, there was no such thing as Jewish Studies. Even though admissions quotas for Jewish students had long been eliminated, and there were Jewish scholars — most notably, Harry A. Wolfson — there was still the sense that Jewishness wasn’t something to be studied or celebrated at the austerely Protestant institution. It was something to be sublimated.

“One went to [Harvard] to become a sort of English gentleman,” Butwin says smiling. “I wasn’t shedding my family history, but publicly, I was.”

The irony for Butwin, of course, was that it was his love of Jewish literature — one nurtured by his mother, a book dealer, political activist, librarian and translator of Sholem Aleichem — that had initially put him on the path toward the life of a literary scholar. Despite becoming a Victorianist and oft-described Francophile, Butwin never did abandon his literary and cultural inheritance.

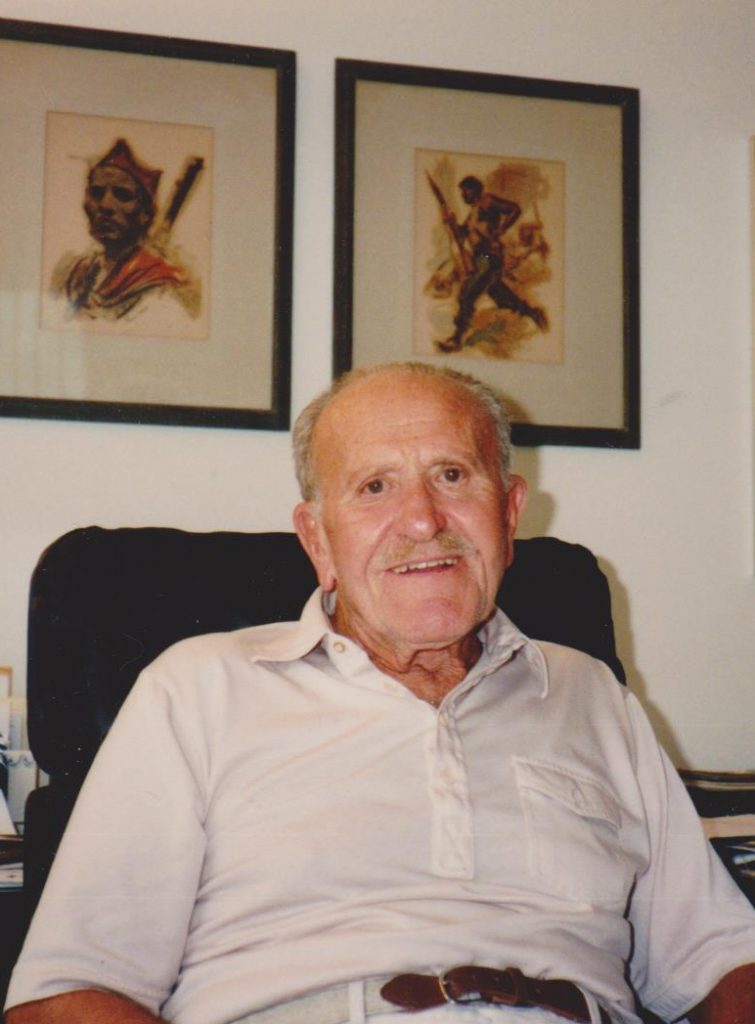

As Butwin now prepares to retire from his position as a University of Washington professor of English — a position he has held for nearly 50 years and in which he introduced some of the UW’s first courses on modern Jewish literature and culture — he looks back on his academic path, one that always led him back to his roots. Even now, he finds himself working on a dual biography of his parents, Julius and Frances Butwin, as well as a collection of interviews with Jewish veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War.

“The line I’ve always used comes from Horace Kallen, a Harvard educated philosopher and German Jew who wrote the landmark essay ‘Democracy versus the Melting-Pot‘ in 1915,” Butwin says. “Toward the end of the essay, with masculine terminology, he writes a man can change his clothing, his style of living, his wife, but he can’t change his grandparents. You run helter skelter into the modern world, but then do a button hook, spin around, look back and you realize you’re not exactly looking backward.”

Family history

It’s impossible to understand Butwin’s intellectual and professional life without tracing it through his family history. His mother, Frances, had moved to the US from Warsaw, Poland before World War II. She met Butwin’s father, Julius, in 1931 through the mediation of the Jewish Daily Forward. Frances entered an essay contest in the English-language supplement: “I am a Jew and an American.” She lost the contest, but her piece was printed. Julius sent a fan letter. Two years and 4000 pages later they were married. The letters serve as the basis for Butwin’s biography of them.

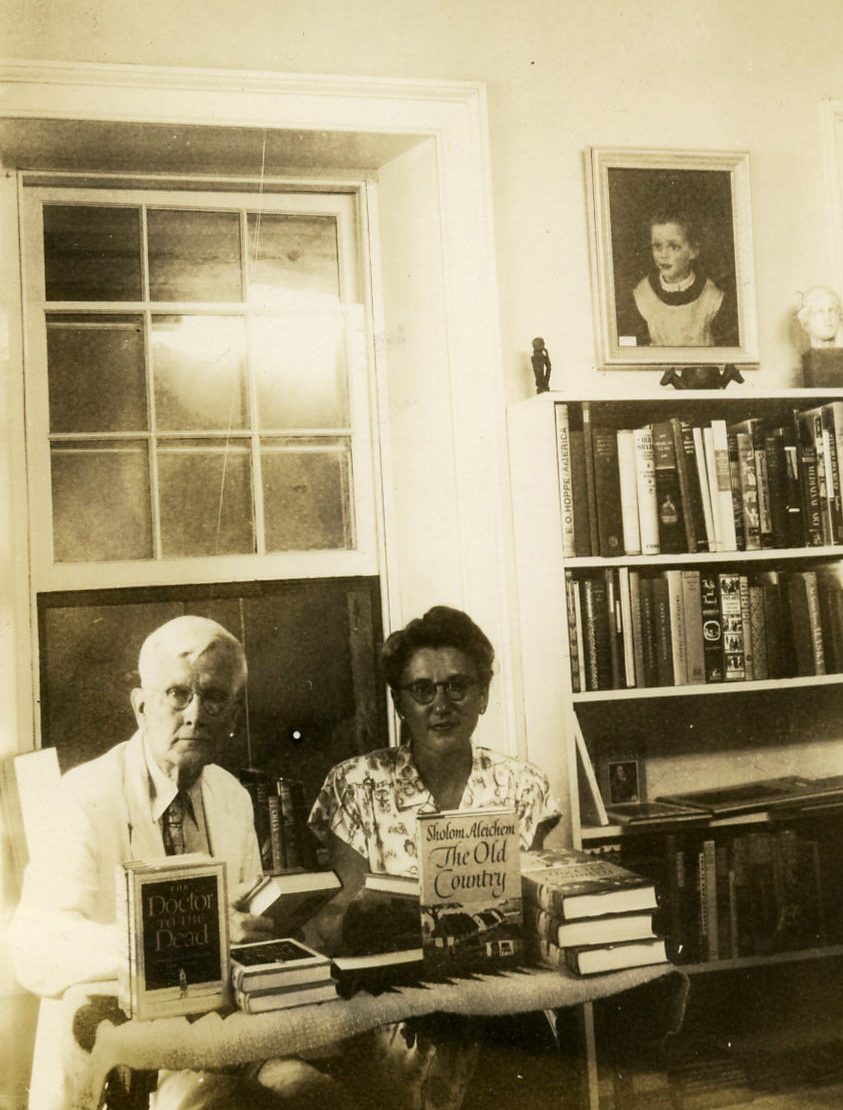

Frances Butwin at a book signing for her and Julius’s translation of Sholom Aleichem’s “The Old Country,” alongside author John Bennet, 1946.

Throughout the 30s and early 40s, the two, who were both members of the Communist party, ran a bookstore in Minneapolis that served as a place for Jewish leftists to congregate. Butwin remembers the house always full of books, records, and people. Sadly, Julius passed in 1945, shortly before the publication of the “The Old Country,” the first volume of their translations of Sholem Aleichem. Butwin was just two.

By that time, the world Butwin’s mother knew as a child in Warsaw had also been obliterated. “Every kid that she was in school with was dead,” Butwin says. “She kept all the pictures they’d continue to send through the 30s. None of them grew into full womanhood.”

With the postwar rise of McCarthyism, a few “terrifying” visits from the FBI, and three mouths to feed, Frances moved away from her political and literary aspirations to pursue a career as a professional librarian. Part of Butwin’s motivation for writing a biography of his parents has been not only getting to know his father, but also his mother.

Though they were incredibly close — they would later collaborate on the writing of a critical biography of Sholem Aleichem in the Twayne series (1977) — Butwin acknowledges that there was much that he couldn’t know of his mother. “She was often depressed; she had to work very hard. There were no men in her life. I got to see another side of her in the letters she exchanged with my father. Writing the biography is also a way of recovering a kind of vitality of a very personal and local nature between my parents in their youth,” he says.

Even at Harvard, Butwin was already concerned with keeping his mother’s intellectual and creative passions alive. In 1968, Butwin shared funding he had received with his mother so she could complete a book she was writing for a children’s publisher on Jews in America. “It was one of the brightest ideas of my life,” Butwin says. “I’m truly proud of it.”

For a year, Frances rented out an apartment in Cambridge, took night classes at Harvard, and worked on her book, while Butwin wrote his dissertation. “She wrote her book in a way that inspired me to write my thesis, though never with her efficiency,” he says.

Recovering Yiddish, building Jewish Studies

As Paris, UC Berkeley and Cambridge exploded in protest that May, the two of them, nearly done with their respective projects, rented a room at a nondescript motel on Cape Cod. Butwin brought along a book called “College Yiddish.”

“The irony was that there wasn’t a school outside of Brandeis and yeshivas teaching Yiddish,” Butwin says. “My mother was totally amused by that book and going through it together was a delight. It allowed my mother to demonstrate her fluency and revive it. Both my parents were native speakers of Yiddish, but after my father died, she didn’t have much need for it. I didn’t hear much Yiddish, except when my grandmother would visit, or older relatives. My exposure was thin, my literacy thinner.”

Two and a half years later, Butwin landed a position as a professor at the UW, with the support, he says, of Edward Alexander, who was then a professor in the English department. The two had met while Butwin was an undergrad at the University of Minnesota. Not only did they share a love of baseball and Victorian literature, but “Eddy was also intensely engaged in promoting Jewish studies as a concept and a program here at Washington,” Butwin says.

The problem was that many saw the teaching of things like Yiddish and Yiddish literature as remnants of the past. “The assumption was that, particularly with Yiddish, Jewish studies was always already over. It was not considered a vital living thing,” Butwin says.

But that didn’t stop Alexander, who eventually became the first chairman of the UW’s Jewish studies program. “I remember the Americanists were afraid of the competition when he went to the department to offer a course on Jewish literature. After all, who were the great American writers in the 1960s and 70s? Bellow, Malamud, Roth. Even Salinger! Up and down the line.”

The first course Alexander got on the books was Jewish Literature in Translation. In the 1990s, Butwin added two more — one on Jewish American Literature and another called Jewish Literature from Biblical to Modern. “I loved the span of that course,” Butwin says. “I’m really unapologetic in teaching a course that paused with biblical and rabbinic poetry, moved through the enlightenment and then blasted into modernity, pausing for the Holocaust and then moving down to current writers and movies and songs.”

The early years of Jewish Studies

Aside from consulting with Rabbi Dan Bridge at Hillel and other faculty on what his new courses should look like, Butwin also enlisted his former student, Michael Weingrad, as a study partner. The two first met when Weingrad took Butwin’s graduate seminar on Victorian literature.

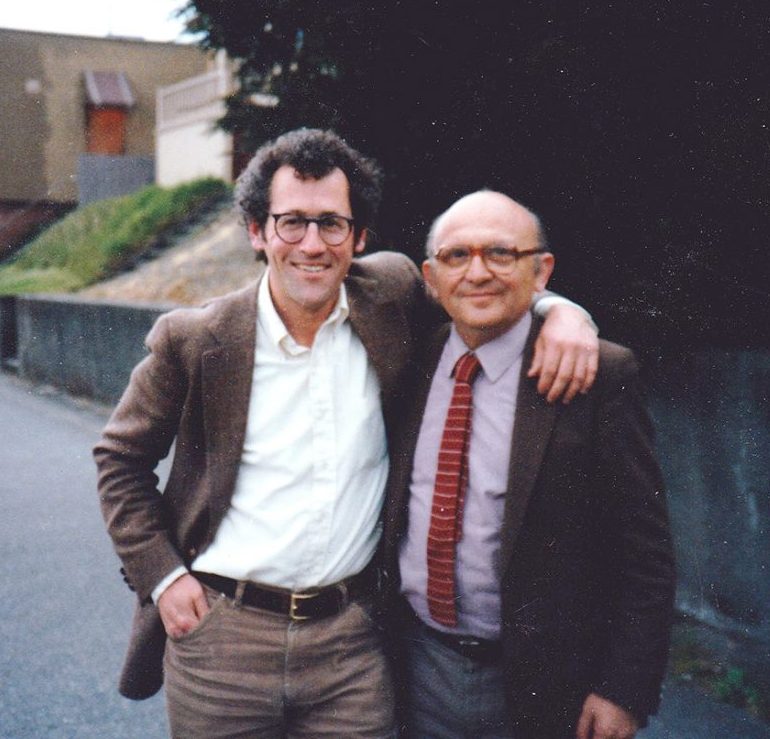

Joe Butwin with Dr. Aharon Appelfeld near the University of Washington, in 1984

Much like Butwin, Weingrad didn’t think he was coming to the UW to pursue an interest in Jewish literature and culture. However, after taking modern Hebrew and then spending a year in Israel, Weingrad says he was looking for deeper Jewish study. That’s when Rabbi Bridge reconnected him with Butwin. The two began meeting weekly at cafes, discussing Jewish texts both sacred and secular.

“Even before we made the more personal connection, in the classroom Joe was such an incredible teacher,” says Weingrad, who is now a professor of Judaic studies at Portland State University. “He just takes such pleasure in the things that he knows and the people that he’s learning from. He lights up, and it’s just a rare example of the way a humanities professor is supposed to be. He’s also the best conversationalist west of the Mississippi.”

Tony Geist, a professor of Spanish at the UW, also uses the word “affable” to describe his good friend and colleague. When Geist arrived at the UW in 1987, Butwin became his first friend. “We became fast friends almost immediately, in part because Joe is so welcoming,” Geist says. “He’s a truly great and open-hearted person. But I was also drawn by the fact that literature is not only his profession, it also has a tremendous personal meaning for him. He lives it, he doesn’t just teach it.”

Exploring leftist Jewish roots: “Salud y Shalom”

But it wasn’t just a love of literature that drew Geist and Butwin together. Both were also the children of Communist party members. Like Butwin, Geist also remembers occasional visits from the FBI to his childhood home. In the late ‘80s, the two of them joined a local “red diaper babies” group that would meet up once a month.

“Our parents really thought they were going to change the world,” Geist says. “It’s been a heavy burden to bear. Their response to fight fascism was to pick up arms. In many ways, they were an unrepeatable generation — ordinary people who did extraordinary things. In the case of me and Joe, we’ve tried to keep the memory of that alive, whether it’s sharing our fascination for Yiddish and Yiddish literature or following up with vets.”

In fact, it was Geist who first introduced Butwin to veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a group of 3,000 volunteer soldiers who traveled from the US to Spain in order to fight Franco’s fascist regime. Most of them were members of the Communist party. All but 150 medical workers were breaking the law (namely the American Neutrality Act) to do so. And one-third of them were Jews.

Butwin decided to record interviews with as many surviving Jewish AL Brigade veterans as he could. Between 1992 and 1994, he traveled from New York to Florida, Chicago to Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle, armed with a tape recorder, a stack of tapes, and a keen sense of purpose. “I never accepted the excuse that it was ‘not in my field.’ That’s bullshit: your field is what you make of it. And I was in a real hurry to do the interviews and collect their stories while I could,” Butwin says.

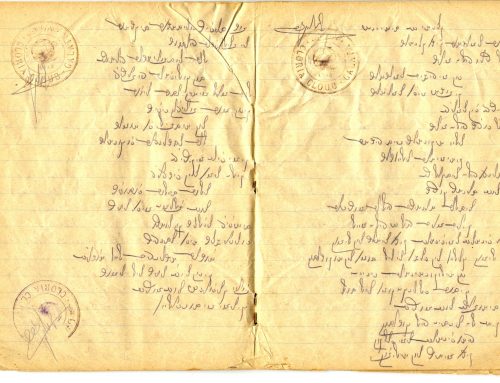

The tapes, which include 39 interviews, along with several transcripts and copies of letters given to him by veterans, sat in a filing cabinet in his office until a few years ago, when he finally dusted them off and, with the support of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and help from UW Libraries, digitized and transcribed them. Now, in collaboration with Geist and Edward Baker, emeritus professor in Spanish, Butwin intends to edit and publish the recordings as a book entitled “Salud y Shalom,” named after the valediction with which Jewish AL Brigade fighters often signed their letters. A digital version of highlights from these interviews is online now.

Passing on a legacy

Just as Butwin’s mother had shared with him a profound love of Yiddish literature, Butwin has shared with his son, Julien, a deep appreciation for oral history. A few years ago, Butwin gave Julien a tape recording of himself and his mother talking about her involvement with the Communist Party in St. Paul. Since then, Julien has started taping conversations between himself and his father.

“My grandmother died a few months after I was born, so I’d never known her,” Julien says. “But to hear that voice and that history was so personally moving to me, because I know it’s also so integral to who [my father] is. And it was very interesting to see a strong culturally Jewish identity go back that far generally and to understand that a huge piece of that for them was storytelling.”

Currently a UW student majoring in chemical engineering, Julien says his appreciation for his father’s dedication to teaching has only deepened since being on campus. “I’ve always really appreciated from a distance the relationships he does develop with his students and how he meets them in a personal way,” Julien says. “But now that I’m at UW and see the size of the classes, I realize how special his strong affinity for the teacher-student relationship has been.”

While Butwin is glad to know that his Jewish American Literature course will be in good hands with Sasha Senderovich, assistant professor of Jewish and Slavic studies, leaving behind the classroom has made retirement a difficult choice for Butwin. “I quite love the theatrics of teaching,” Butwin says. “It becomes almost like an addiction.”

Butwin recalls how, one year, he ended his Jewish Literature from Biblical to Modern course with Jeff Buckley’s version of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah.’ “A student wrote me after how, during that long last note, she wished the note would never stop and the course would never end,” he says. “I recognized that because I had the same feeling.”

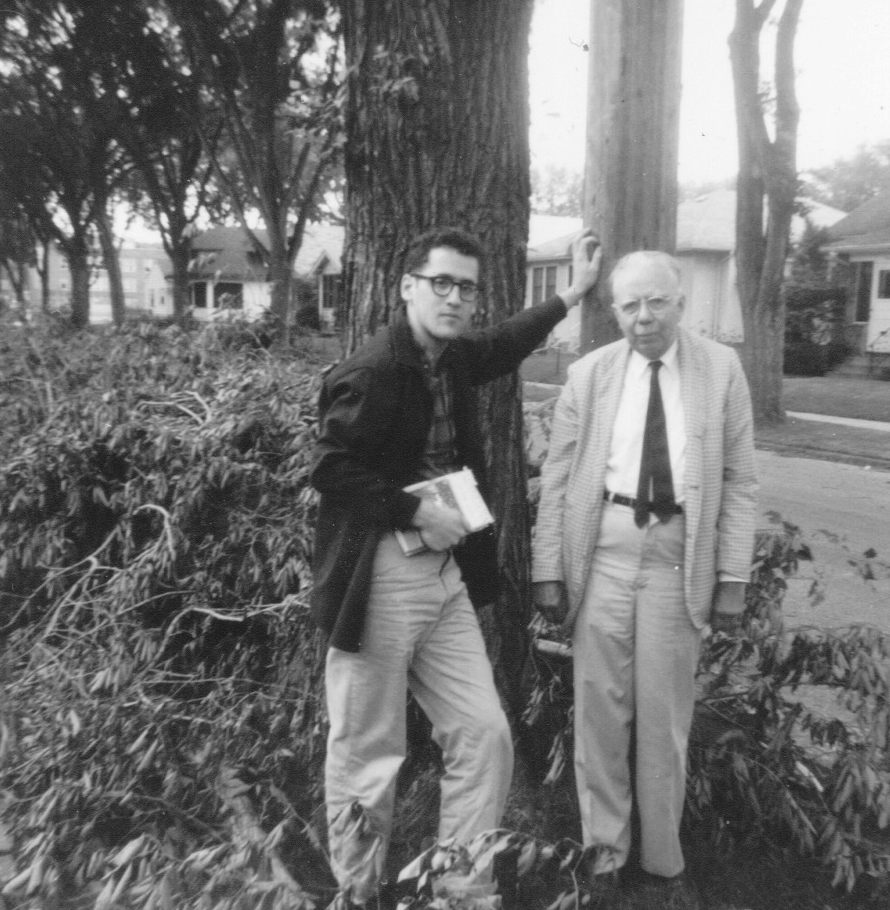

[…] much more about the lives of Frances and Julius Butwin in Denise Grollman’s article “Professor Joe Butwin reflects on how his academic career always led him back to his family roots“, which includes two images of the couple (shown below), as well as images of Professor […]

Unfortunately, the opportunity to register for the Spanish Civil War Discussion was never open. Every attempt to register over several dayswas met with a pop-up saying there were technical difficulties.

Hi, you can view a recording of the “Salud y Shalom: American Jews in the Spanish Civil War” panel discussion with Joe Butwin, hosted by the Sousa Mendes Foundation, online here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JuGxCdHH07I