Mr. Albert Adatto, center in black suit, with students at Toppenish High School in Yakima, Washington, 1941 (Courtesy of Ancestry.com)

“At present I have changed from being an enthusiastic optimist to a very uneasy optimist.” – Lieutenant Colonel Alberto Adatto “Stamboli”

In October 1985, the United States and the Soviet Union were in a nuclear arms race, violence rattled the Middle East, and Iran and Iraq were at the height of their bloody war. For Albert Adatto, a Sephardic immigrant from Istanbul, a former lieutenant colonel and military historian, the future looked bleak. Returning to his native language of Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), Adatto, at age 75 and long since retired from his military career, waxed poetic on the tumultuous political climate.

Inspired by the Rosh Hashanah liturgical poem Avinu Malkenu (“Our Father, Our King”), a petition for God to show mercy on His people, Adatto’s poem Muestro Padre, Muestro Rey expresses his hopes and fears for the years to come. Written in anticipation of President Ronald Reagan’s meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev at the 1985 Geneva Summit, Adatto’s poem prays for wisdom to come to world leaders, including those of the Arab states and Israel. “Forgive our leaders of state that profane religion in making war in Your Blessed Name,” he writes. “Give wisdom to the leaders of the Arab countries and of Israel so they can make peace and so that they will remember they have the same patriarch.” “Da saviduria a los kapos de los paizes Arabos i de Yisrael para ke agan pas i ke se akodren ke tyenen el mezmo patriarka.”

Adatto did not turn to Ladino for literary flourish alone. In the introduction to the poem he writes, “This three-part letter was a unique emotional experience. The idea of an imminent nuclear holocaust moved me so profoundly that it touched the very roots of my childhood language and the marrow of my bones. I thought so deeply in my style of Spanish that I had to pause and think in order to translate it into English.”

Born in Istanbul in 1910, Adatto immigrated to the United States as an infant with his 2-year-old sister Emma, his father Nessim “Sam” Adatto and his mother Anna (née Perahia) Adatto. Nessim worked as a tailor in Istanbul and Seattle, and during the Great Depression he expected that his children would contribute to the family finances. However, his wife Anna insisted that their daughter and son attend the local college, where Albert and Emma went on to pioneer Sephardic studies at the University of Washington during the 1930s. Albert submitted his first master’s thesis for the UW history department in 1939, “Sephardim and the Seattle Sephardic Community of Seattle,” a comprehensive and authoritative ethnography of the Seattle Sephardic experience.

Albert and Emma Adatto as children in Seattle, Washington, ca 1910. (Courtesy of the WSJHS collection at the University of Washington Digital Collections)

A Sephardic historian and Ladino bibliophile, as well as a military officer who spent many years of his retirement traveling the world seeking peace, Sephardic culture permeated Adatto’s life. In addition to conversing fluently in Judeo-Spanish and writing the nearly obsolete Soletreo Ladino script, Adatto produced and sent Sephardic amulets called ojas written in an esoteric script known in Latin as transitus fluvii, literally “crossing the river,” to world leaders and celebrities, including Anwar Sadat and Johnny Carson.

Adatto’s desire for peace as an American intersects with his Sephardic scholarship in a unique way in Muestro Padre, Muestro Rey. In addition to calling for peace in a troubled time, it also addresses starvation in Africa, poverty and prejudice. Adatto pleads to “The Creator of all the creators. God of the Christians, Muslims and Jews, and God of all the faiths” to lessen our impudence, egoism, cynicism and chauvinism: “Amengua muestra inpudensya, egoizmo, sinismo i shovanizmo.”

Adatto passed away in 1996, 10 years after writing this poem, and having seen a nuclear inferno averted. Peace accords had been drawn up between Israel and its neighbors, the Soviet Union collapsed, and as Adatto had prayed, the Iraqis and Iranians finally said “Ya Basta!” “Enough!” Things were looking better. Yet Adatto’s mention of Ecclesiastes is notable: while there is a time for war and a time for peace, there is nothing new under the sun. “Non ay koza mueva debasho del sol.”

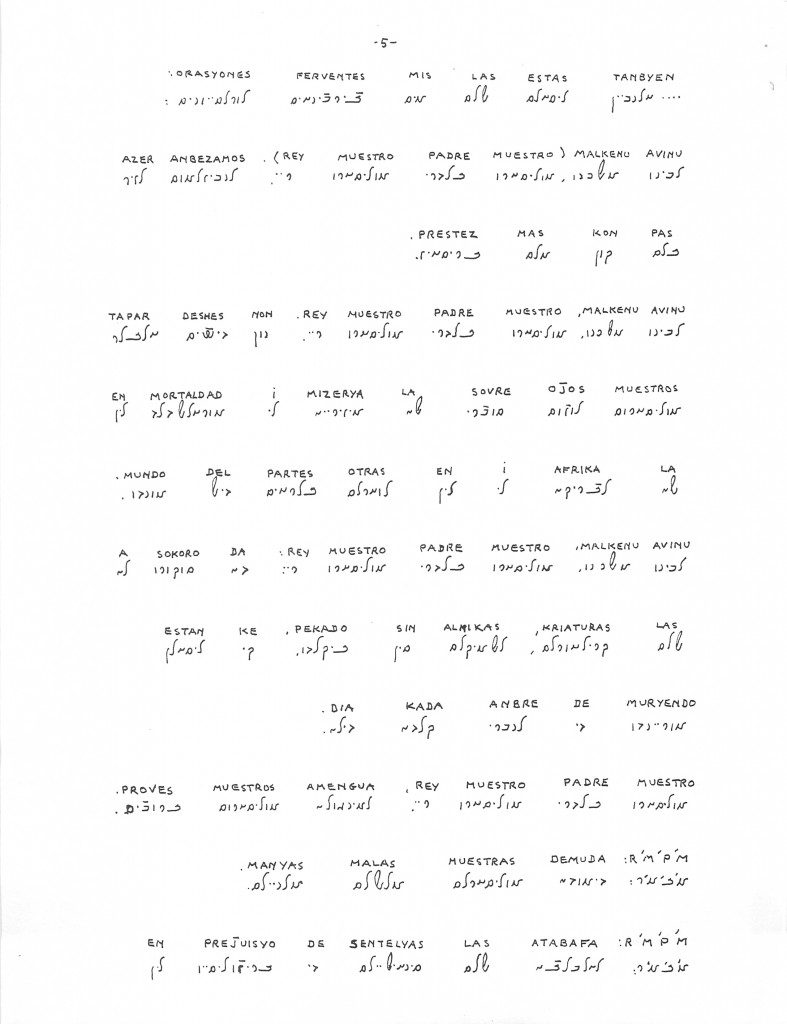

The fifth page of Albert Adatto’s Muestro Padre, Muestro Rey written in both Soletreo and Latin letters

“Salvamos de las bavajadas ke muestros liders mos izyeron englutir por anyos i anyos.” Save us from the drivel of our leaders, who have made us swallow it for years and years.”

Our sincere thanks to Seattle Sephardic community member Al Maimon for providing us with a copy of Muestro Padre, Muestro Rey, one of the many items available in the Henry Benezra Collection. We are truly grateful to Richard Adatto for generously allowing us to include his father Albert Adatto’s Ladino library in the Sephardic Studies Collection at the University of Washington.

Can you elaborate on Stamboli. I am searching for truth.

Dear Kathy, “Stamboli” is a way Sefaradim from Istanbul self-identified. Sefaradim from Rhodes and Salonica were known as “Rhodeslis” and “Saloniklis”.

Ty, in this instance, has “Stamboli” been added specificially to show that he was from Istanbul, or did he use it as a nickname? I met him briefly in 1976, and he was a towering presence (physically and metaphorically).