Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1613).

On the surface, the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah commemorates the rebellion of the ancient Hebrews against their Hellenic oppressors and the miracle of a tiny amount of oil that burned in the candelabra in the rededicated temple in Jerusalem for eight days. That miracle is celebrated today by lighting the hanukkia (as the eight branched menorah or candelabra is called) and the consumption of delicacies fried in oil: latkes among the Ashkenazim and burmuelos among the Sephardim.

Certain legends surrounding Hanukkah have been uniquely preserved among Sephardic Jews. These legends captured in Ma’ase ha-Yehudit and Megillat Antiochus involve the most gruesome and shocking scenes: a Jewish woman who beheads a Hellenistic king; a Greek soldier who rapes a Jewish girl; and Greek-Syrian soldiers, so intimidated by the Hebrews, that they spread horse semen and pig blood all over themselves in the desperate hope that they will ward off the powerful angels of Israel. These “lost” stories of Hanukkah—preserved among Sephardim, and right here in Seattle—emphasize the martyrdom and heroism of the ancient Hebrews that early twentieth-century Jewish leaders drew upon to inspire a sense of Jewish national pride.

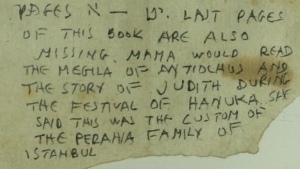

A Mother’s Tradition Yields Some Clues

Our first clues about these additional Hanukkah tales emerged in an inscription in one of the books in the extensive library of Albert Adatto. Born in Istanbul and raised in Seattle, Albert and his sister, Emma, later pioneered the field of Sephardic Studies at the University of Washington in the 1930s. As children, they learned about many customs and traditions from their mother, Anna Adatto (née Perahia). As Albert noted on the inside cover of one his oldest prayer books: “Mama would read the Megila of Antiochus and the story of Judith during the festival of Hanuka. She said this was the custom of the Perahia family of Istanbul.”

There are two unusual features of this inscription. First, it refers to a woman, in her role as mother, reading religious texts to her children, an act that traditionally would have been the domain of the father (a topic to address on another occasion). Second, the specific stories pertain to the holiday of Hanukkah. Unlike other Jewish holidays such as Purim, Passover and Shavuot, there is no universally accepted megillah or Jewish liturgical text for Hanukkah. From the holiday prayer known as al ha-Nissim (for the miracles), we learn only the general idea of the holiday: that the Greek rulers sought to compel the Hebrews to forget the Torah, and God intervened with miracles and delivered the People of Israel from their adversaries. But the story of Hanukkah is not usually read in Jewish communities throughout the world, and the earliest sources for the story of Hanukkah were not included within the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible.

One needs to turn to sources outside of the Jewish canon to find stories about Hanukkah, such as the writings of Josephus, a first-century Jewish leader turned Roman court-historian, or the books of the Maccabees. Ironically, the original Hebrew text of 1 Maccabees, which records the main events of one of the most celebrated Jewish holidays today, has been lost, but its Greek translation was preserved by the early Christian church along with 2 Maccabees, which was composed for the Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria.

So what, then, are the Megillah of Antiochus and the story of Judith that Anna Perahia Adatto read to her children? And what do they tell us about Hanukkah?

Digital Versions of Judith

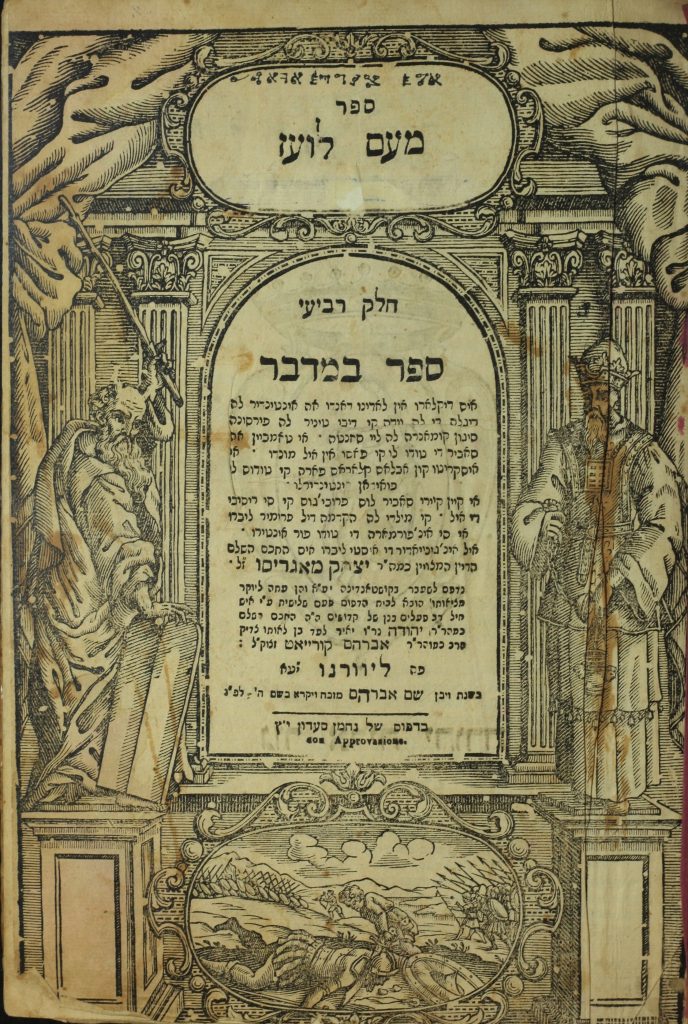

Rabbi Isaac Magriso included Ladino translations of the scroll of Antiochus and Ma’ase ha-Yehudit in the well-known series of biblical commentaries, Me-am Lo’ez, during the discussion of Numbers 8, where Moses commands Aaron to light the menorah. Consistent with the approach of Me-am Lo’ez, these two texts are followed by a lengthy presentation of the laws and customs pertaining to the Hanukkah lights. An elaborate depiction of Moses and Aaron was included on the title page of an 1822 edition of Me-am Lo’ez: Sefer Bamidbar published in Livorno, Italy.

Title page of Sefer Me-am Lo’ez, commentary to the Book of Numbers, courtesy of the Richard Adatto – UW #570.

Ma’ase ha Yehudit also known as Ma’ase ha-Isha ha Yehudit, and Ma’ase de la Yehudit (which could be translated as “the acts of the Jewish woman”) is a colorful midrashic tale based on the Book of Judith. The Book of Judith is of unknown authorship and date, but formed part of the Septuagint, the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, and celebrated the saving feats of a pious Jewish widow over a foreign king, Nebuchadnezzar, and his invading army. Although the Book of Judith was never included in the Tanakh, some medieval rabbis referred to the story in their commentaries and rulings. A thirteenth–century rabbi, Rabbenu Nissim of Barcelona, and the Sefer Shulhan ha-melekh (the Ladino translation of Rabbi Joseph Caro’s Shulhan Aruh including the glosses of Rabbi Moshe Isserles), indicate that Jews should eat cheese on Hanukkah to commemorate a miracle that transpired when Judith fed cheese to an evil Greek king.

Let us examine the episode via the Ladino translation of the Ma’ase ha-Yeudit preserved in the Me’am Lo’ez. The tale begins as follows:

Ma’ase akontesiyo en dias de Aleforne, rey de Yavan, rey grande i fuerte i el mucheguo sivdades i reys fuertes i destroyen sus palasiyos i palasiyos ardiyo en el fuego.

“This story occurred in the days of Aleforne, king of Greece, a great and mighty monarch, who conquered many cities and powerful kings, whose palaces he torched with fire.”

The story continues: “In the twelfth year of his reign, he turned his attention to Jerusalem the Holy city, determined to conquer it as well.” Marshaling an enormous army of swordsmen and archers, Aleforne said to them: ‘In Jerusalem there dwells a nation whose faith is strange and who flaunt the kings commands – a people of cheats and liars. Against Jerusalem let us march at once. Let us make war upon them so that the name of Israel shall be no more!'”

In short, the story tells us of a time in Jewish history when the leadership of Israel was prepared to surrender Jerusalem to the Greek-Syrian forces of the Seleucid Empire. Infuriated by their cowardice, Judith, a beautiful and righteous widow, chastised Israel’s leaders for their faithlessness, informing them that God will deliver Jerusalem from foreign oppression. Feigning defection to the enemy camp, she adorned herself with golden robes, precious stones, rings and bracelets, and scented her body with perfume. Upon seeing her beauty, the king was overcome with passion and said to his advisers: “Who will not go to war against them [Israel] for these women?!”

Judith cunningly arranged a night in the Greek king’s tent. She fed him cheese and “more wine than he’s ever consumed in his entire life.” She then proceeded to decapitate him in his stupor and, as graphically depicted in the text, slashed him over his entire body. Judith returned to the Hebrews, where she victoriously presented the severed head. The Greek military, now leaderless, fell apart. Judith then commanded the people of Israel to attack. When the Greeks found their headless king steeped in his own blood, one of his officers cried out with a terrible shriek, “A single Israelite woman has brought about this horror!”

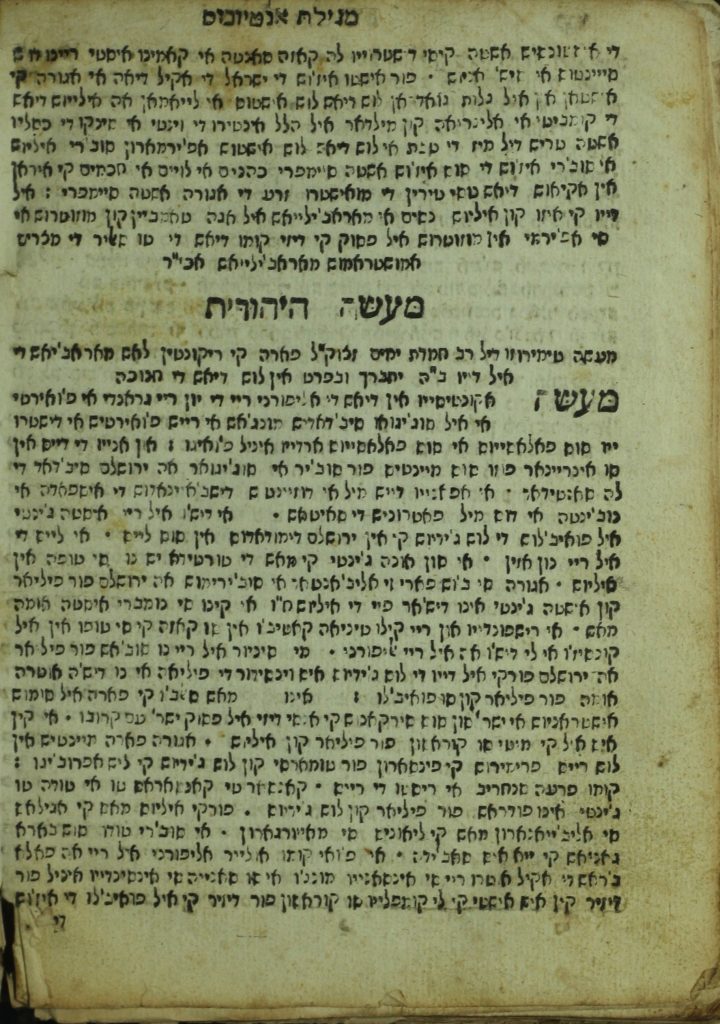

The Story of Yehudith from Sefer Sha’are Kodesh published in Salonica, 1799. Courtesy of Richard Adatto.

According to this legend, it is the courage and faithfulness of Judith that initiated the devastating Jewish victory over the Greeks. Their leaders fled, and the Israelites became rich from the spoils of war. The Jews repented and Judith dedicated the wealth of the Greek king to the Temple in Jerusalem. For three months Israel held celebrations in honor of Judith. For the rest of her life, and for many years after her death, no attempts were made to subjugate the Jewish people and the land of Israel remained tranquil. It was truly a time about which it can be said, “The Israelites, however, had light in the areas where they lived” (Exodus 10:23).

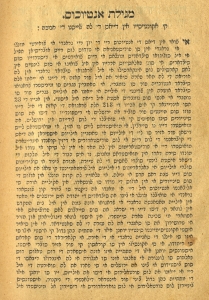

Texts about King Antiochus

Megillat Antiochus (also known as Megillat Hanukkah, Megillat Yavanit, and Megillat Hashmonaim) describes the Maccabean revolt, the central episode commemorated in the holiday of Hanukkah. Like the story of Judith, modern scholars question the events described in Megillat Antiochus. The classic Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), for example, calls it a “spurious work.” Some attribute Megillat Antiochus to the students of Hillel and Shamai. The original Aramaic text was translated into Judeo-Arabic in the tenth century by the famous Babylonian rabbi Sa’adia ben Yosef al Fayyumi (Saadia Gaon), who called it Kataba Bene Hashmona’i, which he held in high esteem. The Jews of Yemen have preserved both the Aramaic and the Judeo-Arabic texts within their communities to this day. (Click to hear Mori Salam Kohen ben Saliman read Megillat Antiochus in Aramaic.) In his commentary to Babylonian Talmud (Sukkah 44b), the thirteenth-century rabbi Isaiah de Trani writes that the scroll of Antiochus was read publicly in the synagogues of Italy during Hanukkah. The first known printed version of the text in Hebrew appeared in 1568 in Salonica, then part of the Ottoman Empire, and from there, entered Ladino translations. In the Ashkenazi world, an edition first appeared in Rabbi Isaac ben Aryeh Joseph Dov’s prayer book Avodat Yisrael, published in Rodelheim, Germany in 1868.

Megillat Antiochus too begins with a Greek king who conquers and destroys many cities. This king, identified as Antiochus, the well-known enemy in the story of Hanukkah, unites the nations under him to fight against the people of Israel, whom he denounces in terms typical of anti-Jewish libels across the generations: “Have you heard about those people in Jerusalem? Their religion is so different from ours and they refuse to follow the rulings that we have passed. They blatantly proclaim to be the chosen among the nations and they await the destruction of all peoples…It is not right that I should tolerate such an evil people to exist, and the time has come to make an end of them; let us wipe them off the face of the earth, so that their name will never again be heard in the world. To overcome them, however, our first step must be to prohibit three of their commandments: Sabbath observance, the use of the Jewish calendar, and circumcision.”

Megillat Antiochus describes the savage response of the Greek army to Antiochus’ call to destroy the Hebrews. Inspired by the king’s speech, his general Nikanor wages a cruel war against the Hebrews and besieges Jerusalem. In one of the most devastating scenes, going well beyond the goal of prohibiting the Hebrews from observing their commandments, a Greek soldier seizes the granddaughter of the High Priest of the Temple in Jerusalem. Before the eyes of her husband, the soldier rapes her on top of Torah scroll, which the soldier has spread beneath them. The general himself also gets involved in the sacrilege by desecrating the Temple in Jerusalem with a pig sacrifice and sprinkling the pig’s blood upon the altar.

Megillat Antiochus includes additional scenes of Jews preferring martyrdom (Kiddush Hashem) for the glory of God as an alternative to violating the covenant of their forefathers. In one scene, in Jerusalem, a Levite woman recites a verse from the Book of Psalms and leaps to her death from the walls of the city, with her newly circumcised son in her arms, in order to avoid being killed by Greek soldiers. In another instance of martyrdom, Jewish families hide in a cave rather than perform labor on the Sabbath, as decreed by the Greeks. When the Greek army surrounds the cave, the Jews declare, “we would rather die here, close to God, than profane the Sabbath. If we live, we live; and if they kill us, we shall die.” The soldiers place logs at the entrance to the cave and set them on fire, killing a thousand men and women.

While focusing on the heinous details of the assault of the Greeks, Megillat Antiochus also describes vengeful responses of the Hebrews. At the negotiating table with Nikanor and his ministers, the High Priest of Jerusalem, Yohanan, has his own tricks up his sleeve. Yohanan initially agrees to obey the commands of the Greeks and accept subjugation. After the meeting concludes, Yohanan asks to speak with Nikanor in private to discuss the details of the peace treaty. When alone, Yohanan offers a short prayer and then reveals a sword concealed in his robe and plunges it into Nikanor’s heart, killing him, before fleeing on foot. He sounds the shofar of revolt in Judea and wages war against the Greek-Syrians.

Megillat Antiochus tells of the subsequent victory of the Hebrew warriors under the leadership of Yohanan against the Greeks. But, in the story, one of the Greek generals survives and returns to Jerusalem with myriads of warriors. The general boasts to Yohanan that this time, his Greek soldiers will not be defeated, as they have prepared themselves for battle by “spreading horse sperm and pig blood on their bodies, in order that no angel will be able to touch us.” The magical elements of the story increase the drama and emphasize the great lengths to which the Greek-Syrians go to try to defeat their powerful Jewish adversaries, who, in this tale (as in 2 Maccabees), benefit from the protection of God’s angels.

The Legends Enter Sephardic Prayer Traditions

But the Ladino translations of Megillat Antiochus and Ma’ase Ha Yehudit also found their way into prayer books, where they took on an added layer of political meaning in the early twentieth century. The most recent versions of the tales are found in Kehilat Ya’akov edited in Belgrade (now the capital of Serbia), in 1904, by Rabbi Ya’akov Moshe Hai Altarats. In this prayer book, Altarats included Ladino commentaries on the liturgy and on Jewish life in general [UW #723, courtesy of Al Maimon]. Notably, scholar Matthias Lehmann has described Altarats as one the first Zionists to write in Ladino, and the way that Altarats explains the significance of Megillat Antiochus and Ma’ase de la Yehudit demonstrate these nationalist aspirations.

Following the text of Megillat Antiochus, Altarats seeks to instill a sense of pride in the Jewish “nation”:

Keridos meldadores,

De este akontesemiento istoriko i de otros komo este podimos pensar komo de baragan fue muestro puevlo, i komo de baraganes tuvimos komo leones kombaten por el Dio, i por sus ley, i pos sus tierras, ombres ke glorifikaron muestra nasion…

“Dear readers,

From this historical incident and others like it, we may contemplate the heroism of our people, and how fearlessly we (our people) fought like lions in defense of our God, and His law, and for their land, men who glorified our nation…”

After Ma’ase de la Yehudit, Altarats adds:

De este akontesemiento puedimos entender komo de mujeres baraganas tuvimos en muestro puevlo las kuales entregaron sus almas por salvar a su nasion… asegun mos salvo en anyos antiguos por mano de baraganes i baraganas i mos rihmira i de esto galut kon ayud( I la)a le veluntad delos buenos i derechos reyenados, amen ken yehi ratson

“From this occurrence we can understand how in our history we have such heroic women who sacrifice their hearts to save their nation… As we were saved in ancient times by the hands of heroes and heroines, so too may we be saved from this exile with the help and good will of the good and righteous kingdoms, amen, may it be Your will.”In other words, Altarats concludes with a hope that the “righteous kingdoms” of his own era—the British, the French, other European powers, and the Ottoman sultan—would step forward and make the Jewish national homeland in Palestine a reality. In short, Sephardic Jewish leaders like Altarats helped turned Hanukkah into a Zionist holiday by referring to these non-canonical tales preserved in Ladino.

Hanukah Alegre! – Happy Hanukkah!

Editor’s Notes:

*We are grateful to Dr. Dov Cohen of the Ben-Zvi Institute and Bar Ilan University. Since the initial publication of this article, Dr. Cohen successfully identified Anna Adatto’s siddur as Sefer Sha’are Kodesh, published in Salonica, 1799. Additional thanks to Dr. Pilar Romeu Ferré for contacting Dr. Cohen about the origins of this previously unidentified prayer book.

*A special thank you to Seattle Sephardic community member Al Maimon for inspiring further research on the texts of Megillat Antiochus and Ma’ase Yehudit. Al’s original presentation of these texts, as contained in Rabbi Ya’akov Moshe Hai Altarats’ prayer book Kehilat Yaʻakov, is available at this link from our 2013 International Ladino Day video (at 1hr 6 minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pAtjjNEL87U

*The English texts of Ma’ase Yehudit and Megillat Antiochus are adapted from Dr. Tzvi Faier’s English translation in The Torah Anthology: MeAm Lo’ez. Edited with notes by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan.

A fascinating piece. Thank you for writing this.

Incredibly written and beautifully described history of our Sephardic Hanukkah story. Kol hakavod.

Good job!

Incredibly biased texts and legends denigrating Greeks, comparing them with nazi germans and praising the “righteous kingdoms” of Europe and among them …the Ottoman sultan! Modern Greeks have build a temple in Salonica (Thessaloniki, spell it correctly, lads, forget about Selanik etc.) for the 7 brave Maccabees and their mother Solomoni, but unfortunately their Jewish compatriots after 1912 wanted a state of their own into the Greek state, or even better, they preferred the city to be conquered again by their Othoman «protectors». Just ridiculous…