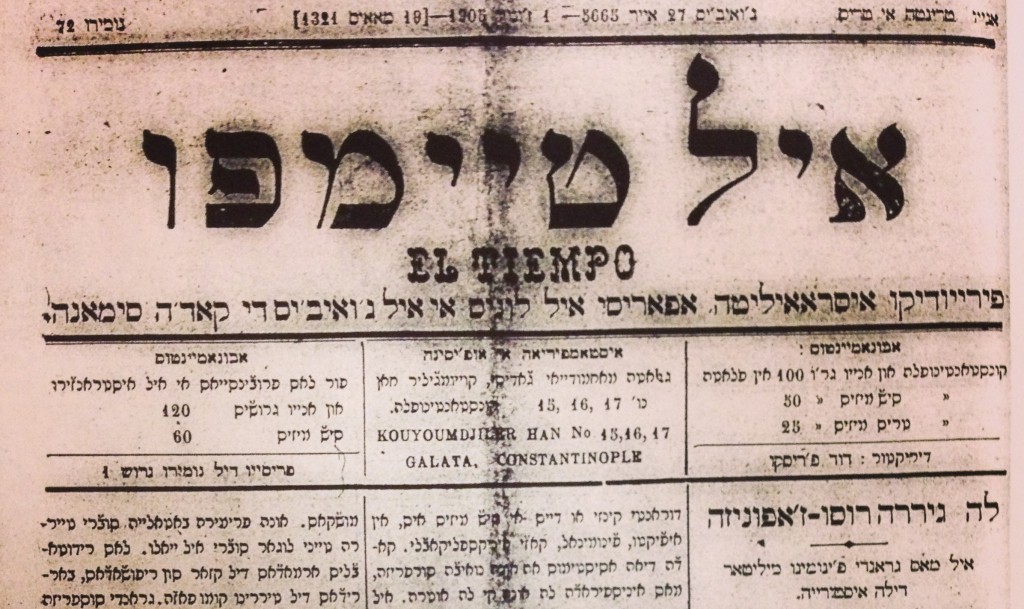

Banner for the Ladino newspaper “El Tiempo,” published in Istanbul.

Tevye’s daughters in Shalom Aleichem’s Tevye the Dairyman (later adapted for the classic musical and 1964 film Fiddler On The Roof) are meant to represent the three typical fates for Russia’s Jews on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution. Jews living in the Pale of Settlement (lands demarcated for Jewish settlement from 1791-1917) could choose, like Tsatyl, to marry a tailor, stay in Russia, and presumably die in the shtetl. Alternatively, they could follow Beilke and her husband to America; or, they could move like Hodl to St. Petersburg, join the Bolshevik Revolution, and fight for legal and social emancipation.

Both Shalom Aleichem and renowned scholar of Russian and Jewish history Yuri Slezkine both fail to include a fourth option in this typography of Russian Jewry: those hopeful Jews that left in the First and Second Aliyah (waves of immigration) for Palestine via the Ottoman Empire. While the story of the early pioneers in the Yishuv is well told, I wonder what became of those Jews who never made it to the Jewish homeland. What are the stories of the Russian Jewish émigrés who instead settled in the métropole, Istanbul, or the Aegean port of Izmir, or even what David Ben-Gurion called the Jerusalem of the Balkans: Salonica?

My dissertation examines this very community, and pays particular attention to their representations in the Ladino press. For the upcoming Jewish Studies Spring Research Symposium on May 2, I will be presenting a version of a dissertation chapter, which offers a historical context for these Russian émigrés as well as a taste of the kinds of representations they received in the Ladino press. From my initial research, several typographies of the Ashkenazim emerge, including the enlightened Maskil (a Jewish enlightened figure from the Haskalah), the persecuted Jewish pogrom victim, the revolutionary, and the Zionist figure, and likely many more. This is an unusual approach for a dissertation in Jewish Studies because it merges two Jewish communities, Ashkenazi and Sephardi, that are usually studied separately. My project is unique in considering the permeability between the two communities and their historical narratives in the twentieth century.

I am interested in how various Jewish historical actors (in particular, the intelligentsia) mobilized these typographies and for what means. How did Sephardi Jews respond to the influx of “los Rusos” (the name they gave the Russian émigrés in the Ladino press) and what kind of community did they create in the Ottoman Empire? Were the historical fates of Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews as disparate as the historiography thus far has made them seem? Ultimately I do not seek to engage in comparative history, but transnational history.

How I came upon this project is a testament to the support and encouragement that I have had through the faculty and staff at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. While those of you who have followed my tenure as a graduate student might remember a project originally more focused on Soviet Jewry, I have made a significant change in direction. The attentiveness of Professors Noam Pianko and Devin Naar identified my unique language skills in Russian, Arabic, Spanish and Hebrew (which Prof. Naar encouraged me to apply to the study of Ladino); they also helped me locate a gap in the scholarly literature that I was particularly well-positioned to address. The Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship, and Coordinator Dr. Hannah Pressman, encouraged me to pursue the topic, allowing me the invaluable advice, comradery, and support from a real graduate and faculty intellectual community.

This year, the UW is hosting Schusterman Visiting Israeli Professor and Ladino expert Prof. David Bunis, and I have been working with him through independent studies to indeed transform my skills in Spanish and Hebrew into actually learning Ladino. I am very grateful for the direction and encouragement of so many members of the SCJS family for making this dissertation a reality, and I look forward to sharing my findings with the Seattle community in May.

As a daughter of Greek Sephardi parents, I have been told that there are many people with the last name Russo amongst us. Some spelled Roussos.

These are Jews of mixed heritage, both Sephardi and Romaniot, who married Eastern European ex pats, who ended up in the Ottoman Empire.