Judaism, Jewish history, and anti-Jewish prejudice: An overview

By Mika Ahuvia, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies & Comparative Religion

Watch a video version of this article

Who are Jews? What is their history? What motivates anti-Jewish prejudice and violence?

By looking at the origins of Jews, and their history as outsiders, starting in the ancient world, we can begin to understand antisemitism and anti-Judaism — two terms for anti-Jewish prejudice.

In particular, learning about two lesser-known cases of anti-Jewish violence in ancient times — the genocide of Jews in Alexandria in 115-117 CE, and Christian violence towards Jews in the early Byzantine period (300-450 CE) — will help to illustrate the underlying forces behind violence against Jews.

Basic info about Jews

Some basic facts about Jews, Jewish history and Judaism.

Some basic facts about Jews, Jewish history and Judaism.

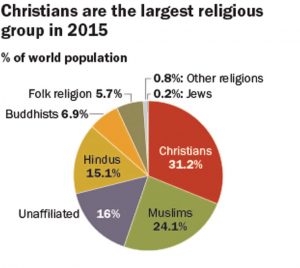

According to the Pew Research Center, about 30% of the world population identifies as Christian, 24% as Muslim and only a very tiny percentage as Jewish.

In 2015, there were 2300 million Christians worldwide, 1800 million Muslims, and 14 million Jews. In the United States, there are 5.7 million Jews or so, or about one or two in 100 Americans, while 71% of Americans identify as Christian and 23% identify as unaffiliated.

Who is Jewish? What does “Jewish” mean?

Jews didn’t start using the word “Jew” as a way to identify themselves until after 500 BCE. In the Hebrew Bible and the Torah, the text that is most sacred to Jews, the term used most often is “the sons or daughters of Israel,” b’nei Yisroel or b’not Yisroel. The term “Israelites” also appears, along with the term “Hebrews.”

Jews didn’t start using the word “Jew” as a way to identify themselves until after 500 BCE. In the Hebrew Bible and the Torah, the text that is most sacred to Jews, the term used most often is “the sons or daughters of Israel,” b’nei Yisroel or b’not Yisroel. The term “Israelites” also appears, along with the term “Hebrews.”

What are the origins of the Jewish people? Asking or answering this question is always tricky, and scholar Steven Weitzman does a great job of discussing this problem in his book “The Origins of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age.”

But setting aside the political dimensions of the question, the origins of the Jewish people lie in the ancient Middle East, at the crossroads of ancient empires, particularly the ancient Egyptian Empire, the ancient Babylonian Empire, and the ancient Assyrian Empire.

Who were the ancient Israelites?

Ancient Israelites originated roughly in the territory of modern Israel, also known as the ancient Levant or ancient Canaan, sometime before 1000 BCE. These people were united by a sense of shared ancestry, myth, ritual and history.

Ancient Israelites believed that they were descendants of three people: Abraham, his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob. Jacob himself is renamed “Israel” in the Bible, which suggests that Israelites had a shared memory of a name change as part of their history.

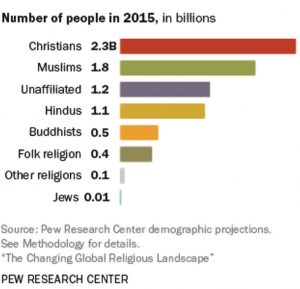

Card showing Moses and the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt published by Providence Lithograph Company, 1907.

The myth that bound ancient Israelites together was the Exodus narrative, from the second book of the Hebrew Bible, a story about liberation from enslavement in ancient Egypt.

The quick version of the story is that ancient Canaan was in a period of drought, and the Israelites went down into Egypt in search of food. They were a minority, and they were eventually enslaved by the Egyptians, until God intervened in history through miraculous plagues to liberate them, with the help of the prophet Moses.

After being freed from slavery, the Israelites were led by God and Moses on a journey through the wilderness between Egypt and Canaan. When they reached Mount Sinai, they were recipients of divine instruction. Eventually, they returned to the “Promised Land,” the area of Canaan where Abraham, Isaac and Jacob had resided centuries before.

Regardless of whether the story of the exodus “really happened” or not, Israelites in 1000 BCE connected with it. When they were told the story about liberation from enslavement, they felt personally invested, in the same way Americans might feel connected to the story of America’s independence from England and the events of 1776, even though they may not be directly descended from people who took part in that conflict.

The story of liberation from Egypt was powerful, and it bound people together as a group.

What is the Torah?

Part of the Israelites’ shared story was the revelation of a sacred text known as the Torah, which literally means, in Hebrew, “instruction” or “teaching.” In Greek, this term was translated as nomos or “law,” and in the Christian Bible, references to “the law” often refer to the Hebrew Torah.

Today, the term “Torah” is understood to refer to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, known in English as Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.

Unrolled Torah scroll in a modern synagogue, showing scripture written in Hebrew.

Many of the laws that are included in the Torah, like prohibitions against murder and stealing, are principles that are basic to a functioning society, and are similar to those found in other legal codes of the time.

What stood out to ancient peoples when they encountered Hebrew law were three particular elements: male infant circumcision, which happens on the eighth day after birth; the observance of the Sabbath as a day of rest; and dietary restrictions, known as kashrut or kosher laws, particularly not eating pork and not mixing meat and dairy.

The “Golden Age” of ancient Israel

The Kingdom of Israel, conquered by the Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE, and Kingdom of Judah in the time of the biblical books of Kings

The “Golden Age” of ancient Israel refers to the time when King David and King Solomon ruled, from 1010 – 931 BCE. King David is associated with foundation of the city of Jerusalem, in the center of ancient Israel, while King Solomon is associated with the construction of the first great Temple in 957 BCE.

Ancient Israelite society was supposedly divided between 12 tribes, 10 of them in the north of the region and two of them in the south.

In 722 BCE, the 10 tribes of northern Israel were conquered by the ancient Assyrian Empire, and only the tribes of the south, in the tiny kingdom of Judea, remained as their own self-ruling political units.

The time of King David and King Solomon was a very short-lived “Golden Age,” lasting only around two generations. Most of the story of the ancient Israelites is a story about a tiny people among other superpowers, trying to maintain their identity and their relationship with God in a polytheistic world of many other competing gods and more successful peoples.

Babylonian conquest and exile of Israelites

In the sixth century BCE, the ancient Israelites endured another catastrophe when the Empire of Babylonia conquered the tiny kingdom of Judea. This conquest could have ended Jewish history, because when the Babylonians conquered ancient peoples, they not only destroyed buildings and plundered wealth, but they exiled the people were were most responsible for creating and maintaining the local culture.

So, in 586 and 587 BCE, some (mostly elite) Jews were exiled to Babylonia. Some Jews also fled to Egypt. This time could be considered the beginning of the Jewish diaspora, a term that comes from the word “dispersion,” meaning the spreading out of Jews across the Middle East, and eventually, the world.

Why didn’t this lead to the end of Jewish history? Part of the reason is that the Israelites believed that God worked through history, even through catastrophes and misfortunes.

The prophet Jeremiah, a very important biblical prophet, criticized his fellow Israelites for not trusting in God fully and for worshipping other gods. But he also promised them that, even though they were being punished through the Babylonian exile, God would call them back to Judea in 70 years (Jeremiah 29:10).

For Israelites of this time, the Babylonians’ destruction of the Temple and exiling of the Israelite elite wasn’t understood to mean that the Babylonian gods had won. Instead, it meant that the God of the Israelites was working through the Babylonians to teach them a lesson.

So, in 586 and 597 BCE, some (mostly elite) Jews were exiled to Babylonia. Some Jews also fled to Egypt. This time could be considered the beginning of the Jewish diaspora, a term that comes from the word “dispersion,” meaning the spreading out of Jews across the Middle East, and eventually, the world.

The Persian Empire and the return to Judea

The Babylonian Empire didn’t last long after its conquest of Judea. As Jeremiah had predicted, about 70 years later, in 539 BCE, the Babylonians were conquered by the Persian Empire.

The Persians pursued a very different policy in how they treated conquered peoples. Rather than exiling elites and attempting to suppress local cultures, the Persian Empire believed that the best way to ensure peace was to restore people to their homelands and help them to live according to their ancestral laws, even giving them money to rebuild their temples.

The Persian Emperor Cyrus, the only non-Jew referred to as “the Messiah” (or the “anointed one”) in the Hebrew Bible, in Isaiah 45:1, allowed Israelites to return to the province of Judea. From then on, we find the Israelites called Judeans (eventually Jews) by others. They tend to still refer to themselves as Bnei Yisrael (the descendants of Israel).

These Israelites recognized Cyrus as the King of Kings, but they also continued to live according to their ancestral laws. This era, around 515 BCE, was also when the Torah was written down as a sacred text for the first time. Prior that, it had been transmitted orally, through memorization and recitation, as part of an oral tradition.

What united the Jews at this point, around 500 BCE? They had an allegiance to one God, and shared legendary ancestors and the foundational myth of the Exodus from Egypt. They also maintained the distinctive rituals of the Sabbath, and had a sense of God working through history, all recorded in the Torah.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Empire

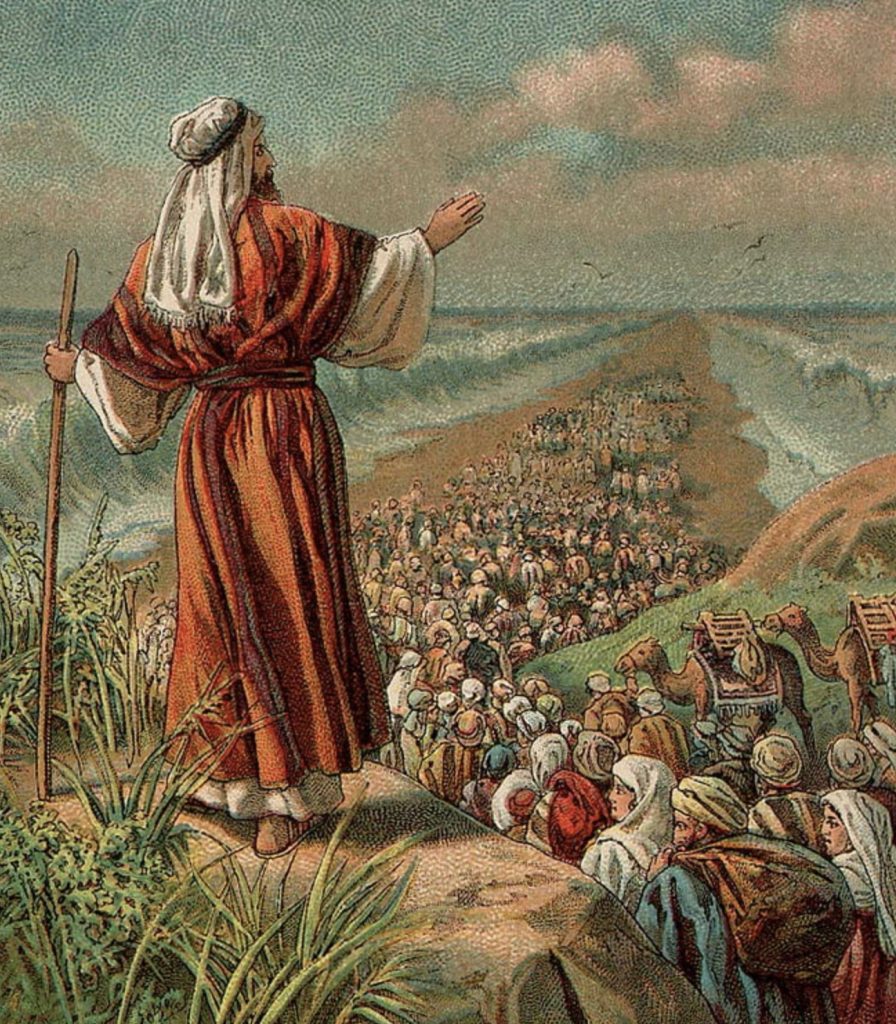

Detail from the “Alexander Mosaic,” a Roman floor mosaic showing a battle between the army of Alexander the Great and the Persian army, dated to around 100 BCE.

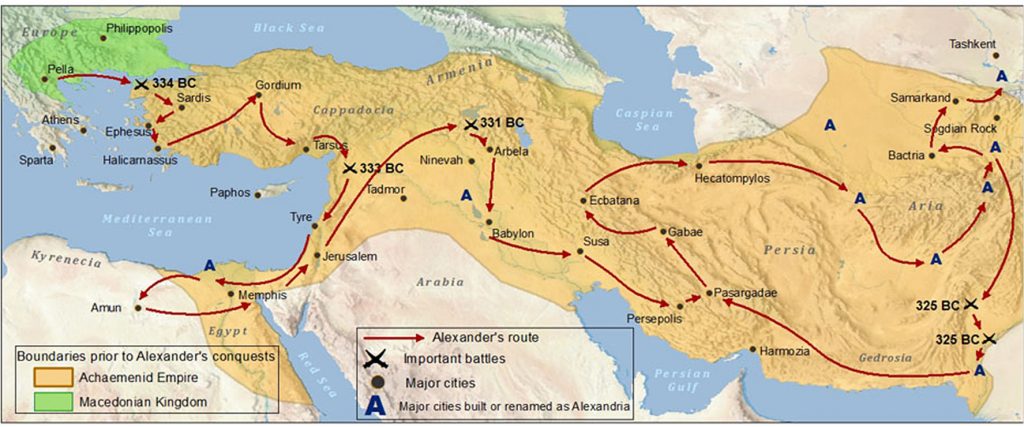

The next empire to impact the Jews and Jewish history was the Empire of Alexander the Great. Alexander came out of Greece in 334 BCE, and conquered an amazing amount of territory. These conquests, and the spread of the Hellenic (Greek) Empire throughout the region of the Middle East, accelerated Jewish habitation in other locales.

Jews ended up joining Alexander the Great’s armies, serving in the armies, and traveling with him to other parts of the world.

In areas that the Greeks conquered, Alexander would establish cities named Alexandria. These Alexandrias (labeled “A” in the map) were spread across the Middle East and the Mediterranean. The most famous ancient Alexandra was probably the one in northern Egypt.

Many Jews ended up traveling as mercenaries in Alexander’s army and relocating to Alexandria in Egypt, where the famous Library of Alexandria was located.

Everywhere that Alexander conquered and formed a city of Alexandria, he would give his soldiers land grants and allow them to settle down after they retired. By the first century CE, four centuries later, Jewish inhabitants of the Alexandria in Egypt were very much a part of the Hellenistic Empire.

Jews of the first century, “of every nation”

Philo of Alexandria, the famous Jewish philosopher of the first century CE, described the Jews of the first century this way:

“For so populous are the Jews that no one country can contain them, and therefore they dwell in many of the most prosperous countries in Europe and Asia, both in the islands and on the mainland.

And while they hold the holy city where stands the sacred temple of the Most High God to be their mother city [meaning Jerusalem], yet those which are theirs by inheritance from their fathers, grandfathers and ancestors even farther back, are in each case accounted by them to be their fatherland, in which they were born and reared, while to some of them, they have come at the very time of their foundation as colonists as a favor to the founders.”

-Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus 46

In her analysis of this text (page 79), scholar Cynthia Baker points out that what Philo seems to be saying is that Jews had a hybrid identity, with Jerusalem as their mother city, their metropolis, but their “fatherlands” everywhere. For four centuries, they had been traveling with Alexander and forming residencies in other parts of the world.

So already by the first century CE, Jews seem to be identifying as Jewish and Alexandrian, Jewish and Roman, Jewish and Asian, Jewish and Syrian, Jewish and Macedonian — hybrid identities.

In other texts, for instance texts of the New Testament such as the Acts of the Apostles, the author, who we associate with the apostle Luke, says, “It happened that there were staying in Jerusalem Jews, pious men, from every nation.” (Acts 2:5)

What does it mean to say that there were Jews from every nation? This seems to recognize that there were many Jews living all over the world who identified as Jews and also as something else.

So, who were the Jews in ancient times? They may have started out as Israelite inhabitants of Canaan. They spread out throughout the Mediterranean and into Asia, united by allegiance to one God, a sense of shared ancestry, a history and distinctive practices. All of these details can be found in the sacred texts of the Torah and the rest of the Hebrew Bible.

What is Judaism?

Judaism is in part an ethnicity, in part a religion, and in part a culture. How can it be all three things at once? This is a complicated question, and you can read more about it in the book “How Judaism Became a Religion,” by Leora Batnitzsky.

Judaism is in part an ethnicity, in part a religion, and in part a culture. How can it be all three things at once? This is a complicated question, and you can read more about it in the book “How Judaism Became a Religion,” by Leora Batnitzsky.

In fact, if you ask Americans who identify as Jewish, some identify as Jewish by religion, and some identify as Jewish with no religion. An interactive online calculator on the Pew Research website displays these statistics.

To make a really complex matter short, Judaism is an ethnicity, a religion, and a culture, but also transcends those categories.

What are the most important beliefs in Judaism?

How can we summarize Judaism quickly? Luckily, this has already been done by two ancient sages, or wise leaders.

The ancient Jewish sage Hillel, who lived in the first century CE, was asked to summarize the entire Torah, all of Judaism, quickly, while standing on one foot. How did he do it? Hillel said, “What is hateful to you do, not do to your neighbor. That’s the entire Torah. The rest is commentary. Go study.”

Interestingly, Jesus, who is most associated with the religion of Christianity, was also asked to summarize the most important parts of Judaism at around the same time. People asked him, “What is the most important commandment?”

Jesus gave two answers. His first answer was that the most important part of the Torah was: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one.” Jews might recognize this as the Sh’ma prayer, which is found in the Torah (Deuteronomy 6:4).

Beginning of the Shema prayer in Hebrew: “Shema Israel, Adonai eloheinu, Adonai echad.” “Hear, oh Israel, God is our God, God is one.” Via NCSY Education, Shema Translated and Explained.

And the second thing Jesus said was that the most important part of Judaism was: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” Then he said, “There is no other commandment greater than these.” (Mark 12:29)

These two responses, from Hillel and from Jesus, were quite similar: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” and “What’s hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor.”

It’s important to note that, from early times onwards, there was significant common ground between Judaism and Christianity.

What has the term “Jew” meant over time?

What has the term “Jew” meant across history, especially to non-Jews?

What has the term “Jew” meant across history, especially to non-Jews?

As Cynthia Baker points out in her book about the word “Jew,” the term “Jew” at various times in history has been connected to both materialism and intellectualism, socialism and capitalism, worldly cosmopolitanism and clannish parochialism, eternal chosenness and unending accursedness.

Obviously, these ideas are all very contradictory. Interestingly, contradictory connotations don’t just exist for people in Europe and America. In China, for example:

“…anything which is not Chinese is Jewish, at the same time anything which is Chinese is also Jewish; anything which the Chinese aspire to is Jewish, at the same time anything which the Chinese despise is Jewish.”

— Zhou Xun, “Chinese Perceptions of the ‘Jews’ and Judaism” (p.16)

So even in places where there hasn’t been a significant population of Jews, Jews come to stand for all kinds of contradictory things.

How were Jews perceived by other peoples in ancient times?

When ancient Greeks and Romans talked about Jews, they often commented that it was strange that Jews rejected the other gods and were so focused on allegiance to one God.

Greeks and Romans were also suspicious of the Torah, and looked down on Jewish customs. They thought that the Sabbath was a sign of laziness and often criticized Jews as lazy. They thought that circumcision was barbaric, and that Jewish dietary laws were ridiculous and antisocial. So how did these suspicions manifest?

As mentioned before, Jews became soldiers in Alexander the Great’s armies and formed their own civic communities in ancient Egypt.

Like Greek soldiers, they obtained land grants in exchange for service and formed their own communities. They constructed synagogues, and some of the oldest archaeological evidence for Jews comes from ancient Egypt.

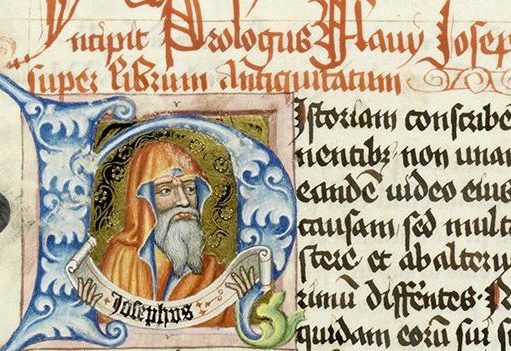

The historian and military leader Josephus portrayed in an illuminated manuscript of his work, “The Antiquities of the Jews,” circa 1466.

The translation of the Torah into ancient Greek also took place in Egypt around the third century BCE, as recorded by the Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews — Book 12, Chapter 2). This translation became the Christian Old Testament.

But, in the first century BCE, there was tension between the Hellenistic or Greek members of the elite and the Jewish community in Egypt.

And it is among these Greek immigrants to Egypt that we find retellings of the Exodus story that paint Jews as undesirable intruders who actually left Egypt because they had a plague and they were sick and were expelled.

While native Egyptians might have also disliked both the Greek immigrants and the Jewish immigrants, it was among the Greek population of Egypt that we find the earliest anti-Jewish writings, where they accuse Jews of separatism and unsociability.

Roman conquest and anti-Jewish resentment in Alexandria

When Rome conquered Egypt in 30 BCE, though, relations between these communities got much worse.

Unlike the Greek Empire, Romans generally saw the inhabitants of their conquered territories as either Roman citizens or non-citizens, unlike the Greek Empire, where Greek immigrants associated with Alexander’s army had a higher status than the local population.

According to the Jewish historian Josephus, the total population of Roman Egypt was 8 million, with 6.5 million native Egyptians, 1.5 million Greek immigrants and 300,000 Jews, over half of whom lived in the city of Alexandria.

When the Romans conquered ancient Egypt, they restructured society. At first, the Romans wanted to deprive all the Greek immigrants of the special privileges they had had before — privileges like special access to education, the ability to participate in politics and athletic competitions, and exemptions from certain taxes. The Greeks protested, because they didn’t want to lose these special privileges.

The compromise that the Romans created was that the Greeks could maintain some of these privileges, and some Jews could too, if they lived in the city of Alexandria itself. But anyone who lived in rural territory was reclassified as a foreigner and lost all of their special privileges.

The Alexandrian Greeks reacted by asserting that this wasn’t fair, that actually all Jews should be classified as foreigners. At the time of the Roman conquest, there was a marked increase in anti-Jewish rhetoric.

To this end, it would be advisable to divide weapons into the following categories: stunning weapons – special devices designed for non-traumatic impact on the human body with the purpose of short-term disruption of its functions, preventing the commission of active purposeful actions (aerosol packages, guns and revolvers, equipped with substances of tear and irritant action, light and light-sound devices of toxic effect, etc.); killing and injuring weapons – objects and mechanisms specifically designed to hit a living target with temporary incapacitation gun control persuasive essay by violating its physical integrity or the normal functioning of the body (electroshock devices and spark dischargers, rubber sticks, pneumatic weapons with muzzle energy up to 7.5 J and caliber not exceeding 4.5 mm, etc.); lethal weapons – items and mechanisms designed to cause death or harm to health, dangerous to human life or to prey on animals (firearms, cold steel, throwing weapons, pneumatic weapons with muzzle energy over 7.5 J and caliber over 4.5 mm)

Greeks accused Jews of being antisocial, of having weird laws or even being lawless, of being misanthropic or hating God, or even of secretly being cannibals and eating humans in secret rituals every year. The underlying idea was: How could Romans give Jews privileges and take away privileges from Greeks?

Even though all Greek immigrants were suffering under the new rules created by the Romans, they targeted their anger at the Jews, who until that point in time had enjoyed the same privileges that they had.

Even though all Greek immigrants were suffering under the new rules created by the Romans, they targeted their anger at the Jews, who until that point in time had enjoyed the same privileges that they had.

In his book “Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition,” scholar David Nirenberg explains that exclusion was important to the ancient Greeks’ sense of themselves. Ancient Greeks saw themselves as a sovereign people with an imperial history, and exclusion — a sense of specialness and superiority to others — was important to their sense of self.

For the Greeks, losing privileges meant that their identity was under attack. Obviously, the real threat was Roman imperialism. Romans were the ones who were taking away Greeks’ privileges.

But the Greeks focused on the Jews. Sometimes they even accused Roman senators of being Jewish. (To be clear, there were no Jewish Roman senators.)

Of course, the advantage of blaming the Jews or directing anger at the Jews is that the Greeks were also able to get the local Egyptian population, who might be resentful of intruders, to join them in their outrage.

The destruction of Egypt’s Jewish community in the first century CE

What happened to the Jewish community under the new Roman Empire? Throughout the first century CE, there were spontaneous attacks, mobs, and riots in the Jewish Quarter of Alexandria in Egypt. In 66 CE, a report from the Jewish historian Josephus states that 50,000 Jews were slaughtered by Greeks. But in 115 CE, matters got much worse.

Only the writings of the victors were preserved, and of course they blame the Jews for rebelling, but it’s also possible that Jews of the city were attacked without any justification.

From the evidence, it seems like the entire Jewish population of Egypt, both within Alexandria and in the countryside, was annihilated.

Surviving tax records from ancient Egypt show that the Roman Treasury confiscated Jewish property and land. And for at least a century after this genocide, Egyptians actually celebrated a day of victory against the Jews.

Anti-Jewish rhetoric was very powerful, and even after the Jews were eliminated from Egypt, later Greek and Roman writers continued to invoke suspicion of Jews. There were political, economic and cultural, religious aspects to the anti-Judaism of this time.

How Christianity separated from Judaism in the ancient world

Jesus was Jewish, his scriptures were Jewish, and his early followers were Jewish. But Jesus was executed by the Romans in the 30s CE in cooperation with the Jewish priests of Jerusalem.

From a Jewish perspective, the Messiah they were hoping for was not supposed to die. Jesus’ death was a real problem for Jews, and was a large part of why many Jews did not believe that Jesus was the Messiah. The movement that eventually formed around Jesus was most successful was mostly formed of ex-pagans, non-Jews.

How did Christian leaders separate their new Christian movement from its Jewish roots? They started promoting Christianity as a fulfillment, or replacement, of Judaism. They claimed that Christians were actually the true Israel, and that they were the ones who had the right to use the word “Israel.”(Romans 9)

They claimed that Jews were too literal in the way that they read their own scriptures, or that they mis-read their own scriptures, and that that was why they couldn’t recognize Jesus as a savior figure.

Later, Christian leaders claimed that if Jews didn’t believe in Jesus, it was because they weren’t meant to. Instead, the story went, Jews were meant to be blind and stubborn so that non-Jews (Gentiles) all over the world would have time to convert to Christianity before the End Times, when Jesus would return to earth. (Romans 11)

When the Romans conquered Judea and destroyed the Temple in 70 CE, this was taken by Christians as confirmation of Christian claims that Jews were wrong (though it is important to note that Jews did not understand it that way).

Consolidation of power by the Catholic Church

In the second century CE, many competing Christian groups existed. Interestingly, as historian Paula Fredriksen writes in her book “When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation,” all of these Christian groups accused each other of being too Jewish. “Jewish” was used as a shorthand for not doing things right, not reading the scriptures correctly, or reading scriptures too literally.

In the second century CE, many competing Christian groups existed. Interestingly, as historian Paula Fredriksen writes in her book “When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation,” all of these Christian groups accused each other of being too Jewish. “Jewish” was used as a shorthand for not doing things right, not reading the scriptures correctly, or reading scriptures too literally.

After 313 CE, when Constantine became the emperor of the Roman Empire and legalized Christianity, things actually got worse for many of these Christian groups, because the Catholic Church started to excommunicate and persecute them. Ironically, the longest period of imperially sponsored anti-Christian persecution began with Constantine’s patronage of the Catholic Church.

Ross Shepard Kramer explains this in his book, “The Mediterranean Diaspora in Late Antiquity: What Christianity Cost the Jews.” As soon as Constantine backed the Catholic Church with the power of the Empire, the Church started targeting Christian nonconformist groups like the Manichaeans, Montanists, Ophitans, Priscillianists, and others.

Ross Shepard Kramer explains this in his book, “The Mediterranean Diaspora in Late Antiquity: What Christianity Cost the Jews.” As soon as Constantine backed the Catholic Church with the power of the Empire, the Church started targeting Christian nonconformist groups like the Manichaeans, Montanists, Ophitans, Priscillianists, and others.

These Christian sects are not well known today because the Catholic Church was very successful in seizing their books, taking over their churches, exiling their leaders and suppressing them as dissident Christian movements.

After the Catholic Church had attacked all the non-Catholic Christian groups, they started going after the pagans — pagan traditionalists who worshiped Greek and Roman gods. From 391-2 CE, the Empire, now known as the Byzantine Empire, prohibited traditional Roman religion and its practice, whether in public or private, on the pain of death or exile.

But after 418 CE, the Empire turned its attention back to the Jews. Byzantine law books from this era, such as the Law Code of Theodosius or Justinian, prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jews, and excluded Jews from the civil service, the military, or from becoming judges. Jews were prohibited from building new synagogues or renovating the synagogues they had, and from converting others to Judaism.

And official Jewish leadership, the “patriarchate,” which had developed after the destruction of the Temple in Judea in 70 CE, was abolished in 429 CE by the Byzantine Emperor.

So Christians started targeting Jews, even though they had had so much in common earlier. And these laws were an expression of the way that the Christians thought about the Jews. The Catholic Church decided that the Jews were to be allowed to exist, albeit in a “state of subjection,” to testify to their own wickedness and to Christian “truth,” until they finally accepted Christ’s Second Coming.

Many Christians in this era maintained the hope that when Jesus Christ returned at the second coming, all Jews would convert — and any who did not convert would be killed.

Anti-Jewish violence in the fifth century CE

Ross Shepherd Kramer includes a clear example of anti-Jewish violence in the fifth century CE in his book, “What Christianity Cost the Jews.”

In the ancient world, Jews were often attacked during the Holy Week of Easter, which commemorates the time when Jesus was crucified. In 423 CE, the Byzantine Emperor proposed a law that stated synagogues could not be seized indiscriminately or set on fire. This is clear evidence that Christians at this time were setting synagogues on fire, or occupying them and consecrating them as churches, which meant, according to the practices of the time, that they couldn’t go back to being a synagogue.

Part of this proposed law from 423 CE also stated that Christians would have to compensate Jews for places that they seized or burned. However, surviving Christian letters shows that these laws never went into effect. Even if they were passed and legislated, they were never enforced. Influential Christian monks like Ambrose or Simeon said that to enforce these laws, to provide restitution to Jews who had been wronged, was an injustice to the Catholic church’s dignity.

So, even when Imperial or secular powers tried to intervene and offer Jews justice following harms they had undergone, Christian leaders were outraged at the idea of compensation and the laws were not enforced.

Anti-Judaism in medieval Europe

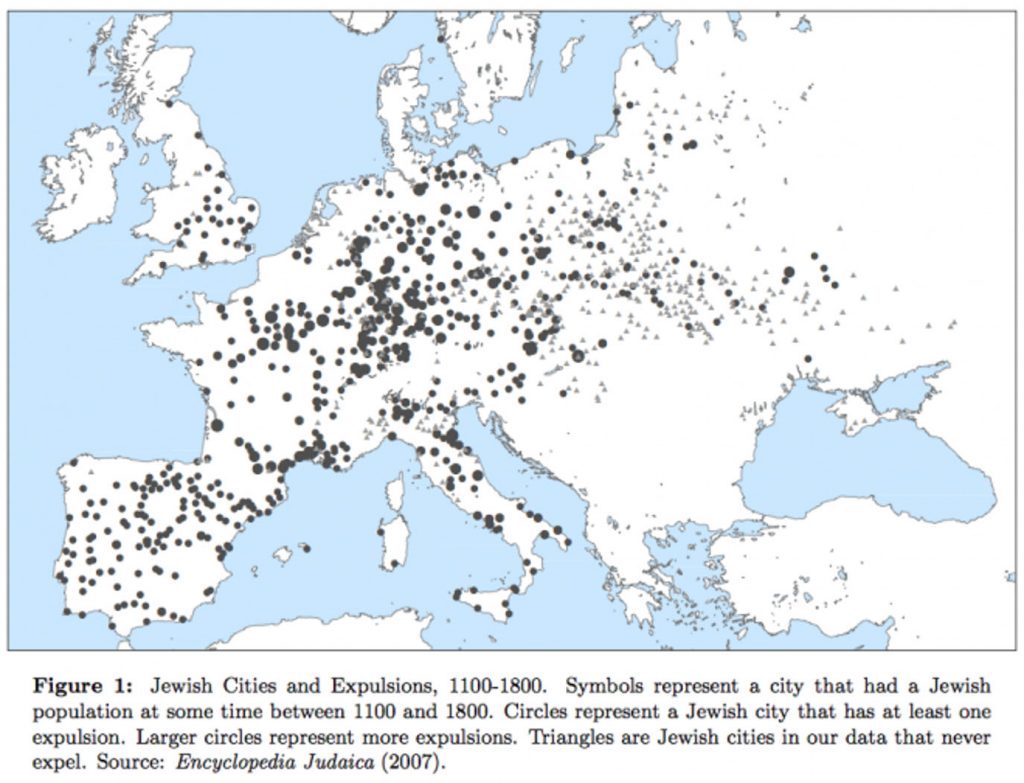

Anti-Judaism continued through the medieval period. Between 1100 and the 1800s in Europe, Jews were expelled from various cities thousands of times, as shown on this map. (Larger circles represent multiple expulsions.)

Economists have correlated these expulsions with times of economic downturn, because of poor weather conditions, corruption, or plagues. Whenever things were going badly and leaders needed a scapegoat, it was useful for them to blame and expel Jews from their cities as a way of “taking action.”

In 1391, in Spain, during the Holy Week of Easter, Christians attacked Jews — without, it should be noted, authorization from the Catholic Church. In this instance, the Christian attackers gave Jews the option of either converting to Christianity or being killed.

Countless Jews were killed, many fled the region, and many converted. Following these attacks, for the first time in millenia, certain areas of Spain no longer had a Jewish population. But, as David Nirenberg points out in his book, “Anti-Judaism: A Western Tradition,” that didn’t mean that anti-Judaism and anti-Jewish prejudice came to an end.

Following this mass conversion, everyone who had converted from Judaism to Christianity was suspected of not being a true convert. And in the 14th and 15th century, the conversation about “Jews” started to shift from one about religion to one based on ethnicity or race — something that could never change, regardless of one’s religion, as discussed in this conversation with historian Ana Gómez-Bravo.

So, even the disappearance of Jews from areas in Spain did not lead to the end of anti-Jewish prejudice and anti-Judaism— the system of ideas was too useful to disappear.

Anti-Jewish prejudice across history

When studying anti-Judaism in history, as well as today, it’s important to keep a set of questions in mind. When anti-Jewish ideas or anti-Jewish violence appear, ask: Who is in charge at this time? What is the position of Jews in society? Who is attacking them, and who benefits from these attacks? How is prejudice translated into social or economic policy by political leaders?

As this overview shows, anti-Jewish attacks are generally not about Jews as people, or about their religious differences. Attacks on Jews are primarily about their fragile status in society, their position as “outsiders,” and about the useful role outsiders can play for political leaders and others as scapegoats during times of crisis.

By targeting, dehumanizing, and attacking Jews, attackers gain political, economic and social benefits for themselves and their followers, particularly in societies where deep inequalities exist.

When studying cases of anti-Jewish prejudice and violence throughout history, it’s important to consider the questions of who, and who stands to benefits, along with an awareness of the many cases of anti-Jewish violence that have taken place across history.

Learn more about anti-Jewish prejudice & history

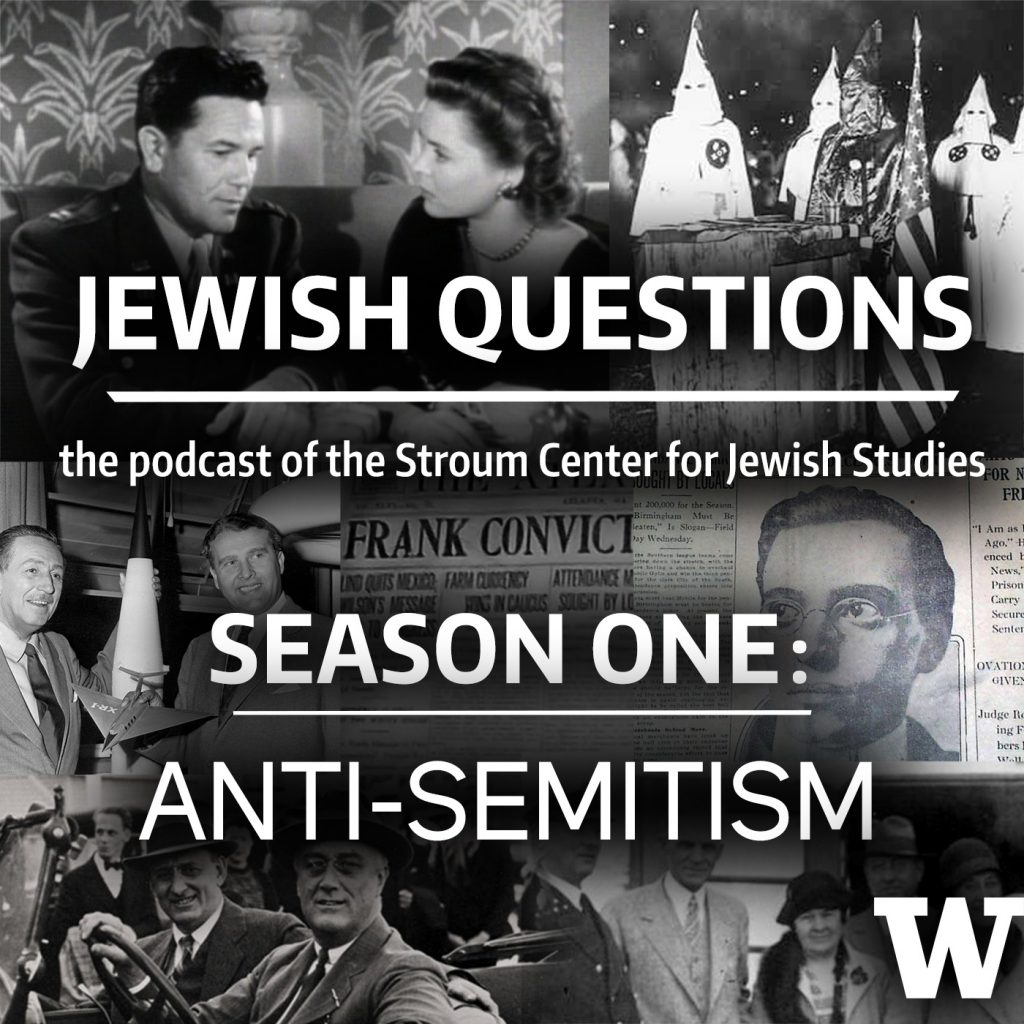

Listen to 30-minute episodes of our podcast series to learn more about Judaism, Jewish history, and anti-Jewish prejudice from professors at the University of Washington:

Listen to 30-minute episodes of our podcast series to learn more about Judaism, Jewish history, and anti-Jewish prejudice from professors at the University of Washington:

- Episode 1. Antisemitism in the United States

- Episode 2. The Rise of Nazi Germany

- Episode 3. Being Jewish in medieval Spain

- Episode 4. Jewish antisemitism?

- Episode 5. Before Zionism