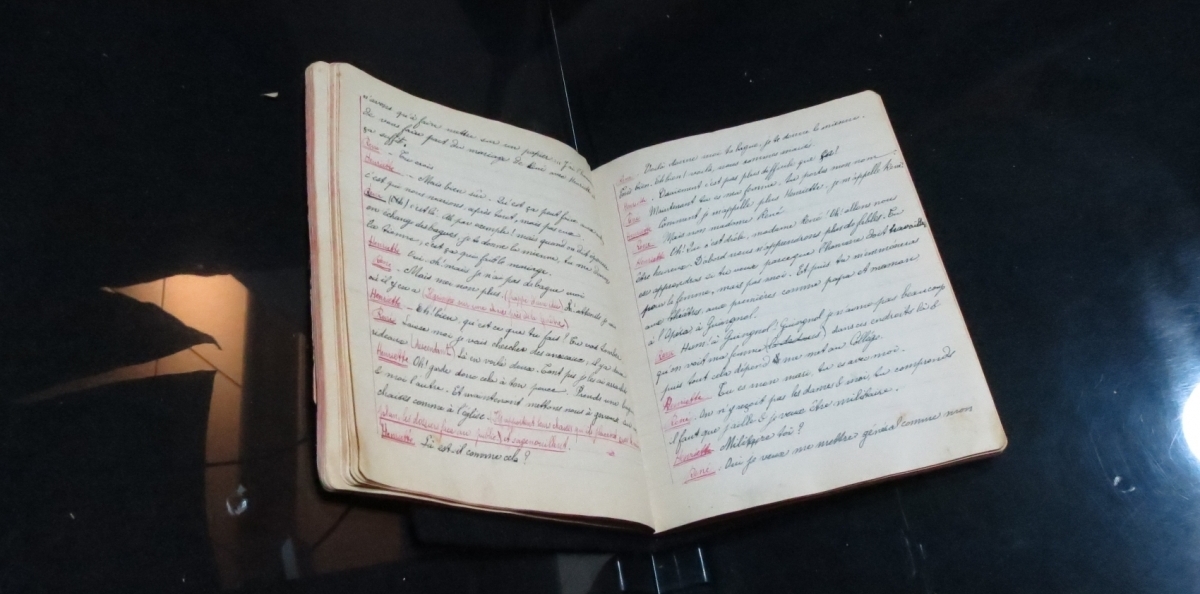

Ready for its closeup: A 100-year-old notebook from the island of Rhodes waits on the plexiglass of the scanning unit at UW Libraries Digital Initiatives Program. Photo by Hannah Pressman.

What does it mean for a private family heirloom to become part of the public record? I found out for myself last month when I brought an item to be scanned for the Sephardic Studies Digital Library & Museum.

For the past several months, the UW Sephardic Studies Program has been renting an archival scanner from Kirkland’s Perfect Image, Inc. In a corner cubicle at the UW Libraries Digital Initiatives Program, technician Tom Donnelly has personally scanned hundreds of delicate items. As you will read in Ty Alhadeff’s upcoming article, the result is an impressive–perhaps unequaled–collection of high-quality scans of extremely rare Ladino items.

I had heard about the massive scanning apparatus and was curious about what exactly was involved in the archival process. As Prof. Devin Naar has often explained, many of the items that have been lent to the Digital Library come from local families’ homes, often dug out of shoeboxes or basement storage bins. What is it like, I wondered, to bring these textual treasures into the light? What is at stake when we transform the physical relics of the past into files, turn memories into megabytes, flatten the texture of crumbling pages into images that flicker on a screen?

After all, these are items that bear immense emotional attachments. A grandfather’s prayerbook, a mother’s haggadah, an uncle’s passport, a cousin’s ketubah–these are things with palpable presence, and an uncanny ability to call to mind the people to whom they belonged. When we convert these items into digital images, does something essential and intimate get lost in the process? Or, is something immeasurable gained?

A Notebook with History

I decided to test the technological waters with a cherished treasure from my own Sephardic family. The item is the French notebook that belonged to my great-grandmother, Estrella Galante. She was born on the island of Rhodes in 1898, one of eight children born to Samuel Leon, a well-off winemaker, and Rebecca Alhadeff. The Leons lived on Calle de la Eskola, so named because it was the street where the Alliance Israélite Universelle school was located. Estrella’s notebook–still intact and legible after a century–is significant because it is a detailed record of one Sephardic student’s educational formation within the Alliance system.

Some background might be helpful here. The Alliance Israélite Universelle was established in 1860 in Paris. As the historian Aron Rodrigue has written in his definitive histories of the Alliance, the organization’s goals were to alleviate Jewish suffering and to advocate for Jewish “moral progress” around the world. The first international organization of its kind, the Alliance took as its motto a Babylonian Talmudic saying: “All Jews are responsible for each other.” On a practical level, the sentiment of religious solidarity translated into concerted efforts by West European Jews, who were relatively integrated into their societies, to offer opportunities for “regeneration” to poorer Jews living in the Muslim lands of the Middle East and North Africa.

The remaining arch of the Alliance school on the island of Rhodes, 2006. Photo by Hannah Pressman.

The Alliance’s founders looked particularly to France as producing modern models of the “the citizen-Jew”: enlightened French national subjects who could also take pride in being Jewish. As a result, French language and culture anchored the rigorous curriculum for the schools that the Alliance built around the Mediterranean.

On the island of Rhodes, the boys’ school was established in 1901 and the girls’ school a year later. My great-grandmother lived virtually across the street from it; today, all that remains of the building is an archway with inscriptions noting the support of Baron Edmond de Rothschild in 1904, and the involvement of colonial Italian authorities starting in 1913. The British bombed the school, along with other structures in La Juderia (the Jewish Quarter), towards the end of World War II.

Estrella’s notebook is dated from 1913-1916, which correlates to age 15 through 18. Nearly all the contents of the notebook are French, with intermittent appearances by Italian (the language of Rhodes’ colonial rulers for three decades) and English. Most of the entries appear to be dictation exercises wherein Estrella copied French literary dialogues and songs. This linguistic feature alone sets Estrella’s notebook apart from the Ladino artifacts comprising the bulk of the Digital Library’s holdings.

When Prof. David Bunis visited the UW a few years ago, we spoke about the Sephardic attachment to French. Why, I asked him, did my great-grandmother and her siblings, who were native Ladino speakers, write each other postcards in French? He replied that knowing French was considered a sign of sophistication and progress among certain generations of Sephardic Jews. More practically, the Alliance education was widely seen as a way for Jews in the Mediterranean and North Africa to find more secure economic opportunities. For this reason, as Prof. Rodrigue observes, demand to get into the schools was extremely high.

The checkered covers of Granny Estrella’s notebook contain more than schoolgirl scribblings (though her handwriting, I should mention, is spectacular–heavily slanted and determined, bordering on calligraphic). They also encapsulate a particular moment for Mediterranean Jews, when the Alliance Israélite Universelle wielded enormous political, cultural, and linguistic influence.

My Trip to the Archive

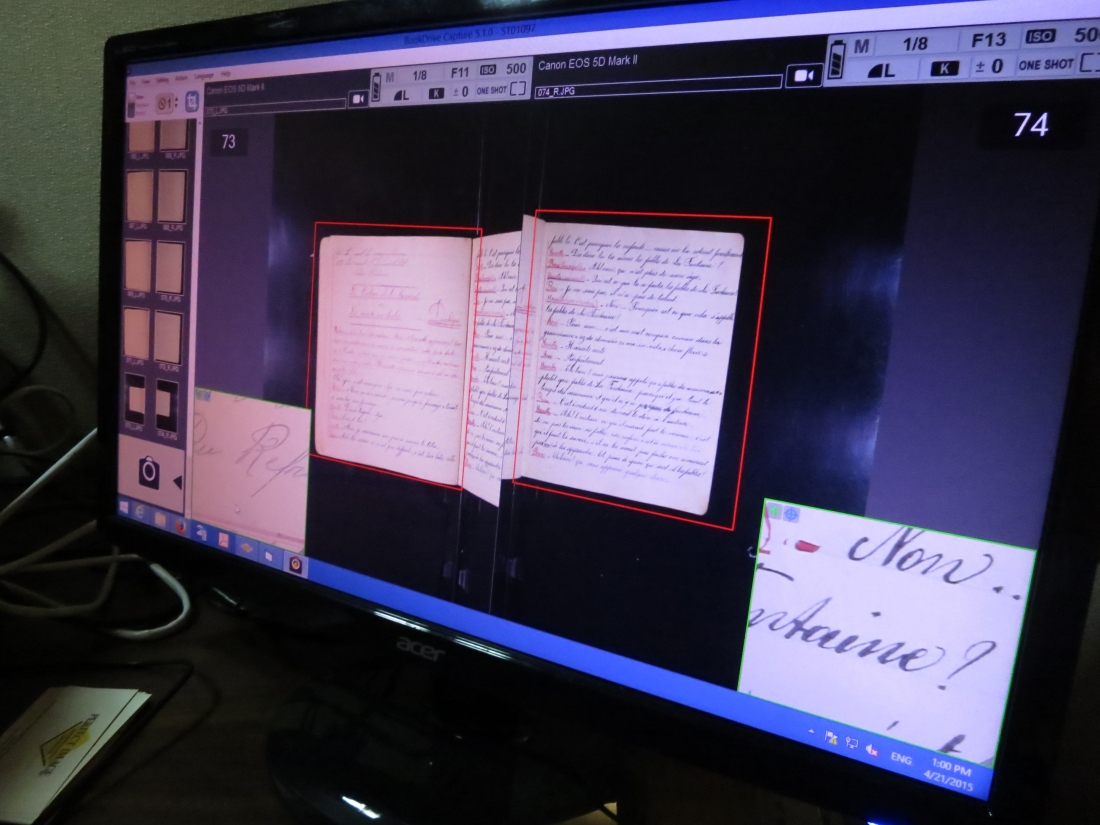

The heirloom notebook has been placed in the Atiz scanning unit operated by Tom Donnelly at UW Library Digital Initiatives. Photo by Hannah Pressman.

The day finally arrived for me to bring my family’s heirloom to the Digital Initiatives wing of the library. I admit to feeling trepidatious as I removed Granny Estrella’s notebook from its archival storage box and handed it to Tom. Placed on the plexiglass, in the crosshairs of two fancy cameras perched on poles, beneath a black canopy, the notebook looked small and vulnerable–quite literally, exposed.

Tom Donnelly has been doing on-site archival projects for Perfect Image for over a decade; his clients have included the Newton Free Library in Massachusetts and the Maryland State Archives. He walked me through the scanning process. Working with the “Atiz” scanning unit, he can do up to 600 pages an hour, but in a typical archival setting that requires turning pages by hand, he averages 300 pages per hour. Many of the Sephardic treasures are so fragile that he has been averaging 160 pages per hour. Spying some white gloves next to the plexiglass, I was delighted to learn that the most delicate items literally get the white glove treatment! All of the images are saved to a local drive and copied to a backup drive, and at the end of each day Tom delivers his results to Ty Alhadeff, the Sephardic Studies Research Coordinator, and his assistant Jeffrey Barton, who track the progress in meticulous spreadsheets.

As I watched Tom carefully leaf through the notebook, I stared at the glowing computer monitor to the right of the scanner. Here, a red box outlines the perimeter of the saved image, while green boxes in the corner show details. This allows Tom to check that every single page has been photographed with the utmost clarity; if there is any blurriness, he takes the photo again. Features of certain pages that I hadn’t noticed before jumped out at me when magnified on the screen.

A computer monitor allows the scanner operator to check closeups of the resulting images for clarity and completeness. Photo by Hannah Pressman.

While working on archival documents, Tom’s guiding principle is for the image to be as close to the original as possible. If a book was rebound at some point and the pages were reassembled in the wrong order or upside down, he doesn’t correct that because that would alter the book’s unique history. If an item like a bus pass or event flyer was left wedged inside a book, he will remove it in order to get a clear picture of the whole page, then photograph it at the end. It was touching to learn that these perfunctory tidbits would also become part of the official library record: an affirmation that what we now view as historical treasures were once used in everyday life.

What, I asked, has been especially interesting about working on the Sephardic Digital Library materials? Tom had two replies, one humorous and one serious. “The most interesting thing has been seeing all the wine spilled on the liturgical texts!” Then he paused and reflected. “Moreso than on other jobs, I am meeting families who have donated pieces to the Sephardic Studies Digital Library. They come onto campus because they want to meet me and see the whole scanning apparatus for themselves. It emphasizes that this preservation project really matters to this community.”

As more communities turn to technology to preserve their pasts, individuals will increasingly have the opportunity to enter pieces of their own family history into the public record. I appreciate the chance to be part of the UW Sephardic Studies Program’s enormous effort to digitize Sephardic culture so that future generations can study it all, from the books to the bus passes.