Graduate Fellow Emily Thompson looks at an oja (special Ladino blessing) from the Albert Adatto collection.

Preserving the Past

There is no doubt that Seattle’s Jewish community is dedicated to preserving its past. Notable examples include the UW’s Sephardic Studies Program’s digitization project, whose goal is to create the world’s largest online Ladino library and museum. In September, local resident Rachel Almeleh released a cookbook documenting a long family history of Sephardic cooking.

But collaborations between the University and the community are not a new phenomenon, as evidenced by the Washington State Jewish Archives, which were founded in 1968 and are housed in the Allen Library’s Special Collections. For the past year, I’ve been volunteering at the archive with Elizabeth Russell, the WSJA’s consulting archivist. As a library student interested in archives, the experience has been wonderful because it’s allowed me to try out many different aspects of archives work: I made a basic inventory of the Lucille Spring papers before they were accessioned (that is, formally taken in by the archives), I’ve created metadata for several oral histories from the archives’ extensive collection, and I’ve contributed to several collection guides.

The Albert Adatto Papers and Sephardic Blessings

One benefit of volunteering with a small archive is that Elizabeth always finds tasks that coordinate with my academic interests. During the summer of 2015, my task was to fill in the details in the collection guide (or finding aid, as they’re known to archivists) for the Albert Adatto Papers. Elizabeth offered me this project because she knows I study Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), and Adatto was a well-known member of the Sephardic community until his death in 1995. He wrote the first Master’s thesis on Seattle’s Sephardic community, “Sephardim and the Seattle Sephardic Community,” for the UW History Department in 1939. (It would not be the last, as graduate work by Molly FitzMorris has carried on the tradition with her 2013 thesis “The Last Generation of Native Ladino Speakers? Judeo-Spanish and the Sephardic Community in Seattle“). I had consulted Adatto’s thesis for research projects, but the details of his life were a mystery to me.

Filling in the finding aid, which can be seen here, required me to physically look through the items that were stored in some 20 boxes. Many were audio recordings of interviews Adatto conducted during his travels around the world. He looked for other members of the Adatto family in Spain, Mexico, and his native Turkey. On one trip to Mexico, he found someone who shared his last name in the phone book and conducted an interview with the somewhat confused man. I learned that Adatto had been in the military, that he worked for much of his career as a school counselor in the suburbs of Seattle, and that he developed an interest in philately and numismatics in his later years. (These are better known as stamp collecting and coin collecting, respectively.) Adatto saw these hobbies as part of a larger interest in peace-keeping; they were his way of helping to create good relations between nations. He regularly mailed gifts of coins and stamps to diplomats and leaders of other countries.

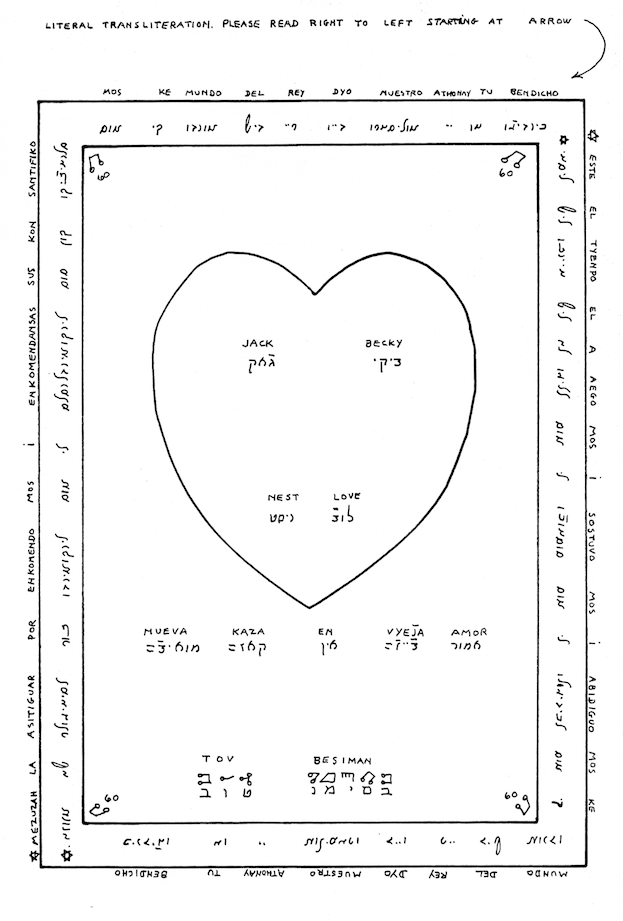

This oja from the Albert Adatto collection at UW Special Collections contains Ladino blessings for a couple’s new home.

Along with these gifts were another type of artifact– something I had never seen or heard of, but found instantly intriguing. They’re called ojas, and there are several boxes of them in the Adatto collection. According to a form letter that Adatto included as part of each oja‘s presentation, this is a Sephardic tradition passed on from his mother’s side. The word oja means leaf, as in a sheet of paper, and they are made to honor and commemorate life events such as marriages, births, or moving into a new home. The ojas are fascinating because they revive an old tradition of ritual blessings or charms for good luck for the 20th century. Each one is carefully presented along with transliterations of the Hebrew characters and an explanation. They’re stored individually in folders or binders. I’ve included some pages from one oja, made for Becky and Jack Benaroya in 1986. The ojas are an interesting record of Adatto’s social network in the 1980s, though some were created for people Adatto didn’t know personally: Johnny Carson, for example.

Visiting the WSJHS Archive

Many people are surprised to learn that there is a difference between libraries and archives. According to the Society of American Archivists, “the primary task of the archivist is to establish and maintain control, both physical and intellectual, over records of enduring value.” Enduring value is a tough thing to define and is certainly subjective, but experience and knowledge of the community served by each archive teaches us which items need to be kept the most. Archives also focus on the concept of provenance–that is, where the artifact was before it arrived at the archives. The Adatto papers, and especially these ojas, are the epitome of enduring value: they reveal one man’s quest for world peace, a social map of Seattle’s Jewish community in the late 20th century, and the passing on of a now-rare written tradition, among other things.

The Washington State Jewish Archives are accessible to the public. Visiting hours are posted on the Special Collections web site, and staff are happy to help first-time visitors find their way around. An online guide to visiting the collections is available on the UW Special Collections website. The Albert Adatto papers are available for public research, though I’d recommend looking through the finding aid first to find out which boxes are of interest. Consulting archivist Elizabeth Russell can be reached at wsjarch@uw.edu.

Editor’s Note: Complementary archival and library materials can also be accessed through the UW Sephardic Studies Program. Contact Ty Alhadeff, the Sephardic Studies Research Coordinator, to find out more about the various items that have been generously donated by the Adatto family for online preservation at the Digital Library and Museum.

Emily Thompson is the 2015-2016 Mickey Sreebny Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. She is a student in the Information School’s Master of Library & Information Science program. She works with physical and digital archives as well as knowledge organization. For her second-year capstone project, she will work with Seattle’s Jewish community to plan and create a union catalogue of community resources. She is also translating Albert Levy’s 1934 Ladino novel Un episodio en la inquisicion into English. Emily holds a BA in English and Spanish as well as an MA in Hispanic Studies, also from the UW.

[…] Archives Post on UW Jewish Studies Blog […]

[…] is working on a Capstone project to archive resources for Seattle’s Jewish community. She wrote about her efforts on the Jewish Studies […]