Are Jewish languages having a moment?

If the sold-out crowd attending Prof. David Bunis‘ lecture on “Ladino / Judezmo as a Jewish Language” last Wednesday night is any measure, the answer is a resounding yes.

Bunis gave the enthusiastic crowd a micro-history of the language alternately known as Judezmo, Ladino, Judeo-Espanyol, Franco, Espanyol, Judeo-Spanish, and several other monikers (a full list is available here). With a deft combination of linguistic theory and material evidence, Bunis portrayed the story of Judezmo as it has unfolded over the last several hundred years. I was struck by the extent to which Judezmo has functioned both practically and symbolically in the textual and religious practices of the global Jewish communities where it traditionally thrived.

Language is always intricately connected to identity, as demonstrated by Sarah Bunin Benor’s new ethnographic study, Becoming Frum: How Newcomers Learn the Language and Culture of Orthodox Judaism. (More evidence that Jewish languages are having a moment–her book was just nominated for the prestigious Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature!) A Hebrew Union College professor and creator of the Jewish English lexicon, Benor provides an analysis of ba’alei teshuva (less observant Jews who return to Orthodox religious practice) that offers an accessible look “at the linguistic and cultural process of ‘becoming.'” Her compelling research shows that what we say, and how we say it, helps to define who we are and where we fit in our community.

Language is always intricately connected to identity, as demonstrated by Sarah Bunin Benor’s new ethnographic study, Becoming Frum: How Newcomers Learn the Language and Culture of Orthodox Judaism. (More evidence that Jewish languages are having a moment–her book was just nominated for the prestigious Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature!) A Hebrew Union College professor and creator of the Jewish English lexicon, Benor provides an analysis of ba’alei teshuva (less observant Jews who return to Orthodox religious practice) that offers an accessible look “at the linguistic and cultural process of ‘becoming.'” Her compelling research shows that what we say, and how we say it, helps to define who we are and where we fit in our community.

Judezmo is a case in point of this phenomenon. Bunis repeatedly emphasized the language’s function as a marker of affiliation with the Jewish community–notably, from internal and external perspectives. Speakers of Judezmo perceived it as a Jewish language and called it djudezmo or djudyó (‘Jewish’). At the same time, non-Jewish neighbors who had continuous contact with Jewish communities, such as the Ottoman Turks, also called it “the Jewish language.” (It should be noted, by the way, that Bunis primarily uses the word Judezmo to designate Judeo-Spanish because many scholars from the Sephardic world have referred to it as djudezmo since the field coalesced in the early 20th century, reflecting the popular use of the term in the community itself since at least 1824.)

Prof. David Bunis, of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, is a world expert on Ladino and Jewish languages.

There is perhaps no scholar today who is better positioned to enlighten us on this fascinating subject: Bunis, professor at the Hebrew University’s Center for Jewish Languages and Literatures, is a world expert on Judezmo. Bunis’ exploration of the language began in his teenage years, when he attended a synagogue in Brighton Beach, New York where all the congregants were from the Balkans and spoke Judezmo. His recordings of their speech patterns and songs became his first research projects in Jewish language scholarship. Since that time, he has been recognized with prestigious awards for his contributions to Jewish culture, including the 2006 Yad Ben Zvi’s Life’s Work Prize and the 2013 EMET Prize for the Study of Jewish Languages.

This year, thanks to the generous support of the Stroum Jewish Studies Program, the SamIS Foundation, the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise, and the UW Division of Spanish and Portuguese Studies, Prof. Bunis will be teaching and sharing his wisdom as the Schusterman Visiting Israeli Professor of Israel Studies. His course offerings will include Introduction to Ladino in the Winter Quarter, making the UW one of the only places in the country where Ladino can be studied on a college campus.

One point that Bunis’ lecture made clear was that in multi-lingual Jewish communities, each language had its own designated role to play, and these roles were reflected in spelling choices and even in typographic design on the printed page. In a classic example of the sociolinguistic situation known as diglossia, Hebrew and Judezmo co-existed but had different functions: Hebrew was used in the sacred sphere, while Judezmo existed in the secular or mundane sphere.

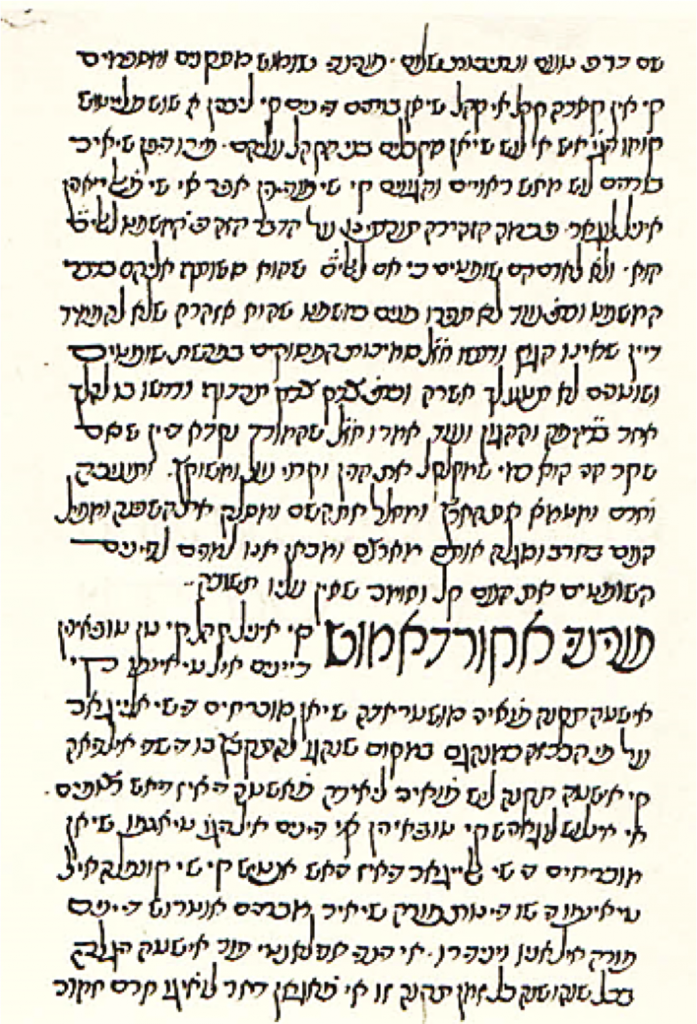

A sample of soletreo, or Judezmo cursive script, from the year 1432. This text came from the Jewish community of Vallodolid, Castille (northern Spain) and listed the taqqanot (communal regulations). Image courtesy of David Bunis.

I also learned that Ladino is the name for the particular type of Judeo-Spanish that was used to translate the language of sacred Hebrew liturgy. Moreover, when Judezmo speakers translated ancient Hebrew and Aramaic texts, they would employ an archaic variety of Ladino to try and mimic the syntax, word order, and style of the sacred original–just as contemporary bible translators like Everett Fox have tried to generate an archaic English to mimic the austerity and grandeur of biblical Hebrew.

Throughout the lecture I was mesmerized by the sheer visual aspect of Judezmo manuscripts, which Bunis’ archival slides rendered in high definition. In particular, soletreo, which is the name for Judezmo cursive script, looked like gorgeous micrographic art in one text from the Iberian peninsula dating back to the early 1400s–before the Jews’ expulsion from Spain. Bunis’ color coding system on another slide made it clear that Judezmo is a syncretic language that, much like Yiddish, synthesizes words from several sources: its geographic origin (Ibero-Romance), loanwords gained by contact with non-Jewish cultures (such as Turkish), and the traditional Hebrew-Aramaic canon.

One element of the evening that was very popular with the audience was a recording of a Ladino version of “Ein Keloheinu” from the Shabbat morning liturgy. Prof. Bunis played a version recorded by Seattle’s own Isaac Azose, the Hazzan Emeritus of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth (and the subject of this recent article by Dr. Maureen Jackson on our web site). The whole audience sang along, in what was perhaps the first collective performance of “Ein Keloheinu” at an academic lecture at UW! Clearly, projects like Azose’s recordings of Ladino song traditions will be critical for the preservation of Judezmo going forward. During the Q&A Prof. Bunis expressed his interest in going into Seattle’s Sephardic community and making recordings of local Judezmo speakers.

Like all good talks, Bunis’ presentation on “Judezmo / Ladino” inspired me to ask more questions about the nature of Jewish languages and what it means to “speak Jewish.” I wondered, for example, about the similarities and differences between Judezmo and Yiddish–a comparative question that stems as much from my own mixed Sephardic and Ashkenazic heritage, as it does from my recent scholarly work on Yiddish culture. Did these languages historically operate the same essential way, allowing Jews to bridge with non-Jewish cultures as they circulated in different regions from medieval times forward? What about internally–did Judezmo speakers have a version of taytsh, the Yiddish translation of the bible that boys memorized in heder (Jewish elementary education in Eastern Europe)?

And, for that matter–how do you say “Yiddish” in Judezmo?

Prof. David Bunis, joined by Prof. Devin Naar, takes questions after his lecture on the history of Judezmo / Ladino on Oct. 9.

As I observed the inter-generational mix of audience members–which included an undergraduate whom I recently profiled for her amazing Ladino translation project–I was also moved to consider the future implications of Bunis’ talk. Will Judezmo experience a cultural reinvention on the scale of the Yiddish revival of the early twenty-first century? Although largely in its “post-vernacular” phase (to cite Jeffrey Shandler’s influential term), Yiddish has enabled creative new expressions of Jewish identity and non-Jewish cultural affiliation across the globe. Last year’s New Voices in World Jewish Music series, which was organized by the UW Stroum Jewish Studies Program and featured young artists exploring new avenues of Sephardic musical expression, suggested that Judezmo is already on its way to a similar phenomenon.

Despite Judezmo’s status as an endangered language, Bunis ended his talk on a hopeful note. He cited universities as absolutely essential places for the continuation of Ladino and Sephardic Studies, and emphasized that the field has been galvanized by the UW’s Sephardic Studies Initiative,which is led by Prof. Devin Naar and supported by a dedicated committee of community leaders chaired by Lela Franco. In addition, Bunis announced an exciting possibility: though it has not been finalized, Dec. 5, 2013 might be declared Primer Dia Internasional del Ladino – the first International Ladino Day. If this comes to pass, I have no doubt that the students, faculty, and Seattle community members who gathered last week for Bunis’ lecture will be celebrating Ladino Day in high style and in song.

Interested in exploring more? Click here for an event listing of all the academic and cultural events organized by the Sephardic Studies Initiative for 2013-14.

Great article, Hannah! You’re lucky to have Prof. Bunis visiting for the year.

Fascinating! I love that Seattle is at the center of this Jewish language moment! Thanks to the Sephardic Studies Program, I’m able to expand out of a Yiddish-centric view and learn about the rich and beautiful history of Ladino, both as language and culture.

Interesting Article. However, the Judeo Spanish vernacular in Morocco is called : Haketia! It is composed, just like the Djudizmo– of basically of 15th century Spanish, but with different additions, which were from: Hebrew, Aramaic, Local Moroccan Arabic, Portuguese and some French, English and Italian.

djudezmo, lengua fablada por nuestros Nonos, de la Espanya antica, esta se disperso no solo en toda la Sefarad, si no por toda la Europa, mediterranea norte, mediterranea sur uniendose a tierras arabes, o mediterraneo oriental, uniendose a tierras turko- otomanas, otros arribaron a la America, dejando de ser Sefarad la Espanya para ser ahora la America la nueva Sefarad, ” la tierra mas lejana ” la genetica sefaradi estara presente, hasta el final de los dias, Rosh hashana, 5775. shalom. ani perezi.

[…] second-annual International Ladino Day, hosted at the University of Washington on December 4th, the Judeo-Spanish (or Judezmo) dialect of Sephardic Jews will bask in the spotlight of renewed international interest. Seattle […]

We have waited so long for young and younger scholars to pursue the study of Ladino, and at last it has come to pass. Kol ha kavod to David and Devin. My course with David at NYU is one that I will always treasure. David’s course notes are kept carefully next to my Brandeis dissertation – “The Ladino Dialect of the Jews of Kastoria, Greece.” I introduced David to my father, Morris Zacharia, who was born in Kastoria and still remembered his soletreo.The only flies in my ointment were the discussions between my father and my maternal grandmother. She was born in Florence, Italy and would challenge my father on some of his Ladino vocabulary. It was an exciting time. We are so fortunate to have Devin promoting Ladino studies. He is such a fine scholar that we know that he will inspire many others. Having attended some of his lectures, I applaud his ongoing work in this field. Bravi to you both!

Very interested to read about this revival of ladino.

I was born in Rodos, Greece, and I spoke ladino with my granny. As a result I am quite fluent in this language and I know lots of its sayings and proverbs. My parents spoke many languages but as they aged they reverted to speaking ladino with me and among themselves. My father even wrote ladino with the Hebrew characters. I was in Rodos in July 2014 to commemorate the 70th year of the deportation of the Sephardi community from the island to the concentration camp in Aushwitz. I was one of the survivors, saved by the Turkish Consul. An Israeli film maker interviewed me in Ladino. Apparently in Jerusalem there is a magazine founded “para la presevacion y fomento del Patrimonio Cultural heredado de los Judios de Rodes” The editor is Mario Soriano.

I live in Cape Town where there is a strong Sephardi community but unfortunately only the older generation speak Ladino, now,

[…] Judezmo is a religious language formed as a hybrid of Spanish and Hebrew. Those who practice Judaism typically know how to read Hebrew. However, Judezmo is an endangered language utilized by mostly Jewish people. […]