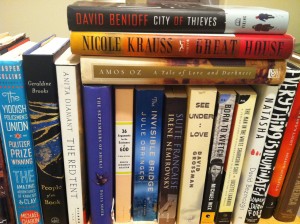

Books with buzz: some recent best-selling books with Jewish connections.

Among the many delights offered by the monthly Hadassah magazine is a little corner column listing the “Top Ten Jewish Best Sellers.” Located with the cultural reviews towards the back of the magazine, the “Jewish Best Sellers” list is obtained from MyJewishBooks.com, one of many online sites devoted to the books read by the people of the, er, book.

The Hadassah list, while always informative, sometimes makes me chuckle. “Really?” I think to myself. “They consider that a ‘Jewish’ book?” Admittedly, I myself am not sure of the criteria that I consciously or unconsciously apply to this list; at some point I must have formed a mental set of boundaries within which I plop books that just feel Jewish to me. I think my confusion at some of the “Jewish Best Sellers” usually stems from seeing a title that has no obvious Jewish content. That then prompts the question, is an author’s Jewish background, or their obviously Jewish name, enough to merit inclusion on the list of Jewish bestsellers, even if the book they wrote bears not a trace of Jewish stuff? What about the reverse situation–would a novel brimming with Jewish themes, written by a non-Jewish author, make the cut?

Academic attempts to address this issue have yielded such worthy anthologies as Hana Wirth-Nesher’s What is Jewish Literature? (JPS, 1994), wherein she eschews as “reductive” any approach that goes according to the author’s Jewish identity. So if biography (or biology) aren’t satisfactory criteria, what else makes a book Jewish: the language in which it was written? Themes of morality or justice that stem from Jewish worldviews? A particular relationship with Jewish religion and sacred texts? The geographical location where it was created? These approaches all pose their own problems. More recently, the eminent scholar of Hebrew literature, Dan Miron, proposed “contiguity” or closeness as a way to think about Jewish writers’ shared positioning. In From Continuity to Contiguity: Toward a New Jewish Literary Thinking (Stanford UP, 2010), he compares the writing of Franz Kafka and Sholem Aleichem, bringing them into thematic and existential contact. (For more, see this excellent review.)

It may be the case that Jewish literature is defined, as Wirth-Nesher says, by its being “indefinable”; and that always, somehow, Jewish literature contains a search for self-definition, an attempt to locate and inscribe one’s story within a particular time and place. However, let’s step back from theory for a second and think about what a “Jewish bestseller” means on the local level. As Lois Goldrich writers in this story, for example, books of classic Judaica (Haggadot, editions of Talmud and bibles) are always bestsellers at Jewish bookstores in the New Jersey area, and several genres vie for readership: cookbooks, non-fiction, memoirs, and popular novels like Sarah’s Key all captivate the customers who come into the stores surveyed for her piece.

Indeed, for the contemporary Jewish audience, there perhaps has never been a better time to be a Jewish reader. Just take a look around–from the Jewish Book Council to the Jewish Review of Books, there exists a plethora of resources helping us decide what to read when we want to read something Jewish. I run a local Jewish book club–which, I can say without a shred of irony, is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream for me–and I constantly run into the problem of having too many books on my wish list for the group. And yes, I do try to figure out which books have buzz, those titles that seem to be, if not technically “bestsellers,” then the ones that everyone’s talking about.

Just as a single book cover can evoke a whole set of memories and remind you of the person you were at the time you read it, a bestseller list can reflect a lot about the zeitgeist of a particular time period in a society. Hence, the New York Times Book Review sometimes includes a snapshot of bestseller lists from previous decades, as a way of reminding us what we were interested in reading (or at least wanted to have on our bookshelves!) years ago. But what if we could go way, WAY back in time and find a “Jewish Best Sellers” list from 1900? from 1850? from 1800? What would that list tell us about the people who were reading Jewish books, however they were defined back then?

This year’s Stroum Lectures make just that leap. On October 22nd and 24th, we have the extremely rare opportunity to travel back in time and examine a Jewish bestseller from the early modern period. Pinhas Hurwitz’s Sefer ha-Brit was, by all accounts, a blockbuster: first published in 1797, it went into thirty-eight editions (including Ladino and Yiddish versions) over two centuries. A mix of kabbalah, science, and ethics, Hurwitz’s book was extraordinarily popular with early modern Jews. Guest lecturer David B. Ruderman will explain what this book can tell us about Jewish readers at a time of immense political and religious change.

Would Sefer ha-Brit make it onto Hadassah’s “Jewish Best Sellers” list if it were published today? Come hear Professor Ruderman, and you just may find out.

Both lectures take place at 7:30 p.m. in 220 Kane Hall, UW Campus. Lectures are free, but advance registration is appreciated. Click here for easy advance registration!

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)