How can a record label carry us across the ocean?

Turkish language records played a unique role in Sephardic dance parties in interwar Seattle on Shabbat evenings (nochadas), and Sephardic homes sported furnishings of a phonograph culture built on the affordability and convenience of records, and the production of both decorative and utilitarian phonographs. Now let us turn to the question of where and when people purchased the 78 rpm records filling Victrola cabinets to elucidate a larger geographical and cultural history behind the Baruchs’ Turkish record collection. Did the couple bring 78s with them when they immigrated to the United States? Or did they purchase them here – or a combination of both?

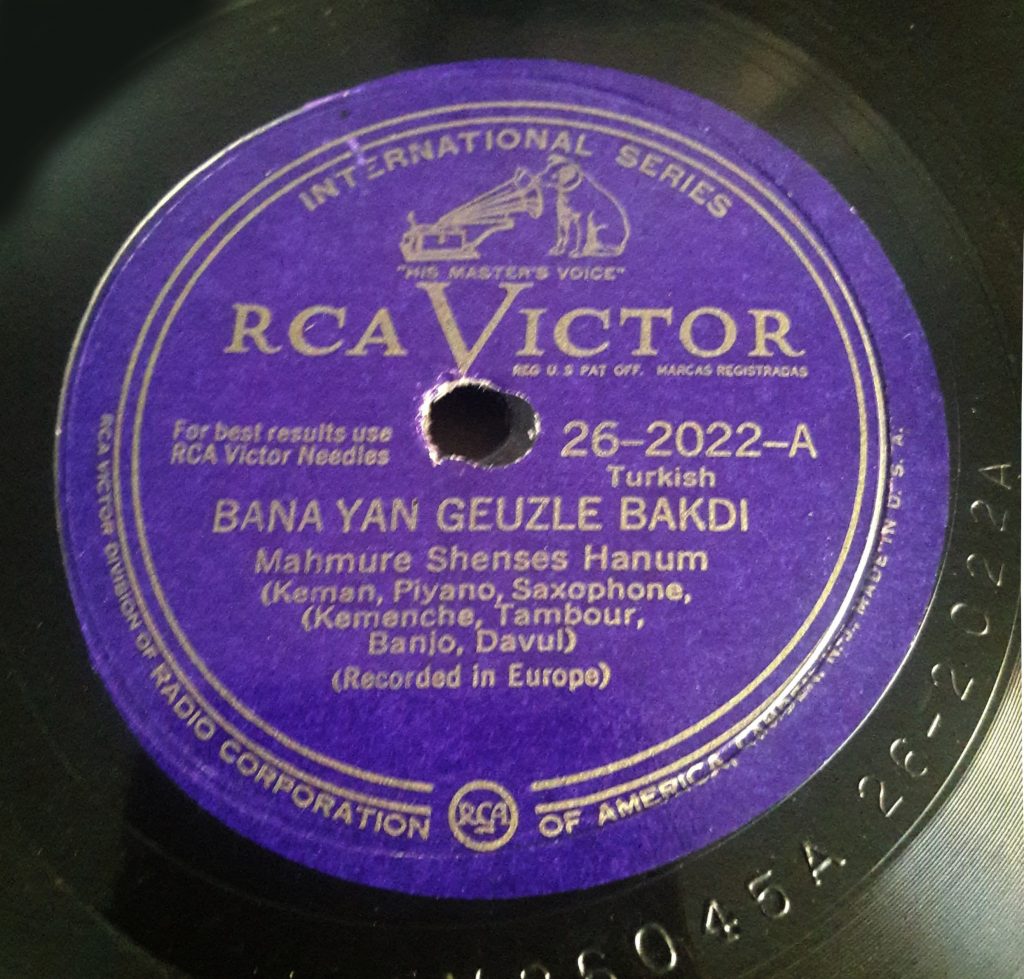

Record by RCA Victor (post-1942). The Turkish song, “Bana Yan Gözle Baktı” (“He made eyes at me”) is sung by Mahmure Şenses, its title transliterated for non-Turkish- speaking customers. (Courtesy Isaac and Rachel Baruch via Ty Alhadeff, ST01381)

A cursory review of the labels on the Baruchs’ records offers some answers. A deep purple label – RCA Victor – signals the 1929 buy-out of the major American company Victor by RCA (Radio Corporation of America); the combined name was only printed on labels after 1942, thus dating this U.S.-produced record of Turkish vocalists Mahmure Şenses (side A) and Safiye Ayla (side B) to two decades after the Baruchs’ marriage in Seattle. The Decca Odeon-Parlophone record must have been purchased in the same period, since American Decca produced the Odeon-Parlophone series in the late 1930s and 1940s. And the Popular, Balkan, and Kaliphon labels all represent small immigrant start-ups in New York City during the 1940s that primarily released recordings of Balkan and Middle East immigrant musicians.

Although numerals imprinted on the records (catalogue and matrix numbers) can help accurately date the recordings, the brands of the Baruchs’ collection alone confirm that their records were produced and purchased in the United States well into the 1930s and 1940s, probably by mail order from New York City or distributors in other metropolitan areas.

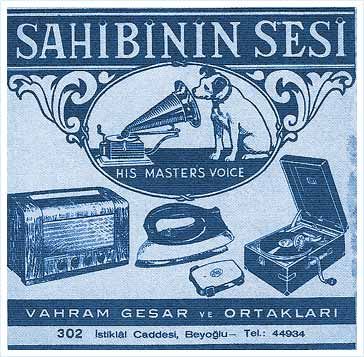

Advertisement for His Master’s Voice agent Vahram Gesaryan’s store in Istanbul (c. 1930s). Vahram and his brother Aram were among the partners who established the London-based label in Turkey in the late 1920s. Source: Mavi Melek.

The Baruch’s may have purchased their records here, but the commercial custom of re-releasing past recordings extends their musical story beyond the United States. The RCA Victor record of the two female Turkish singers, for example, may have been produced in the U.S. after 1942, but the original recording was made overseas (in Europe or Turkey), probably several years to a decade earlier when, according to Turkish language sources, the two singers recorded these songs on His Master’s Voice record label.

To be sure, it was not uncommon for companies to re-release recordings of their own or other companies through manufacturing agreements, subsidiary labels, or corporate consolidations. At least two other records owned by the Baruchs were recorded in Turkey and re-pressed (or reproduced) in the U.S.: the singer Küçük Yaşar (also known as Mustafa Çağlar) on RCA Victor, and Bayan Birsen and Mahmure Şenses on Decca Odeon-Parlophone – all among the most popular and recorded vocalists of Turkish art music and other genres in the first decades of the Turkish Republic. Some like Safiye Ayla and Mahmure Şenses enjoyed their own re-releases in Turkey up to 1950.

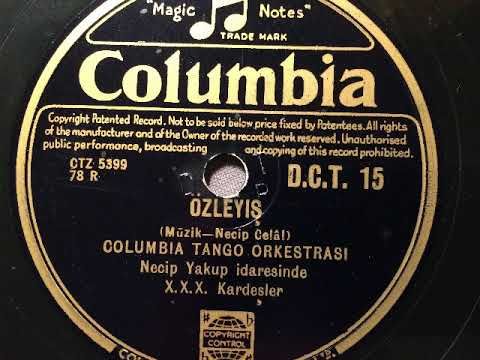

Columbia Tango Orchestra recording of “Özleyiş” (“Longing,” c. 1950). Collection of Radiomuseum Hardhausen.

The songs in the collection, moreover, include tangos and rumbas in Turkish, dances that had become popular in Turkey and globally with the spread of jazz and social dancing since the 1920s. Vocalist Mahmure Şenses in particular had garnered fame for her tango and rumba recordings on Odeon and Columbia, and, like Bayan Birsen, sang tangos with the Necip Yakup Orkestrası, which served as a tango studio orchestra for Columbia Records.

These re-releases add complexity and richness to our understanding of a record collection of mostly Turkish language songs, produced entirely in the U.S. by major companies like RCA Victor and smaller immigrant labels like Kaliphon and Balkan. The records reflect not only an interest in danceable Turkish music over recorded Ladino or Hebrew song, but also in contemporary vocal stars prospering simultaneously in Turkey, beyond the lively Mideast immigrant music scene of major cities like New York.

The dance music, moreover, extends to genres and rhythms associated with the so-called Jazz Age – music refracted through a Turkish vocal, linguistic, and sometimes instrumental aesthetic, and embedded in the richly mixed and contentious musical economy of a young European-leaning nation.

Additional record collections will undoubtedly enrich and complicate our understanding, but for now, the Baruchs’ records testify to a Sephardic household keeping pace, through a globalized recording industry, with contemporaneous musical currents resonating in a musically linked but politically divergent cultural moment in the Turkish Republic. To dance a la Turka – and possibly even to tango a la Argentine – at house parties in Seattle was to participate in a modest, local way in the supply and demand dynamics of a vigorous, multi-genre trade in 78 rpm records on both sides of the Atlantic.