How did Seattle Sepharadim inhabit phonograph culture?

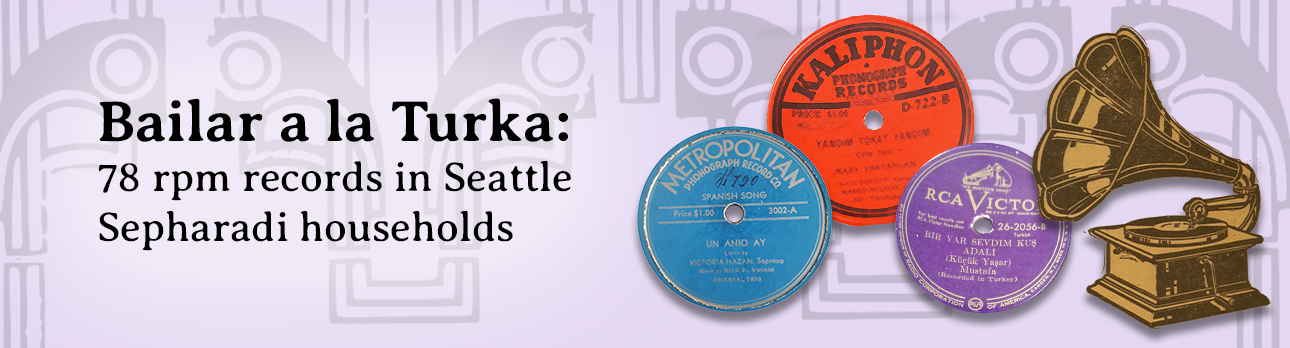

Ottoman ad for cylinder recording of Tanburi Cemil Bey, a renowned tanbur (long- necked lute) player (Ahenk newspaper, Aug 28, 1907). Photo by the author, reprinted from Maureen Jackson, “Mixing Musics: Turkish Jewry and the Urban Landscape of a Sacred Song” (Stanford University Press, 2013).

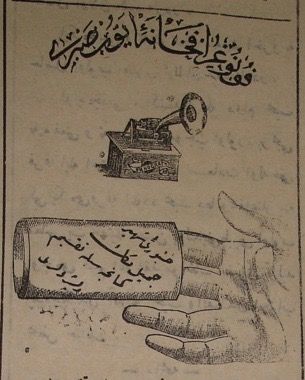

The Saturday night parties (nochadas) remembered by Seattle Sepharadim represent a particular form of entertaining in the community, akin to socializing at a Sephardic, Turkish, Armenian, or Greek café, club, or public festivity – with Turkish records standing in for live music. In fact, some ads for record players promoted the convenience of staying home to listen to music, in contrast to the hassle of going out for a musical event in the evening.

Facilitated by commercial and consumer interest, a growing phonograph culture began to flourish during the 1920s, when new electrical recording improved listening quality; the decreasing cost of records and their equipment expanded accessibility; and recorded music was promoted as equivalent, or even superior, to live performance because of its portability and repeatability.

Even so, 78 rpm records did not supplant diverse live music-making. “In those days before radio or television,” as first generation community members often put it, Seattle’s Sepharadim generated their own forms of entertaining and spontaneous music-making that thrived alongside musical recordings: collectively singing songs, for example, with Ladino, Turkish, and bi-lingual lyrics; telling stories; setting a nice table; having a few drinks.

At the same time, records played a unique role in animating social occasions like dance parties: whether one sang along or not, all you had to do was dance without the necessity of providing informal or professional live music. 78 rpm discs conveniently produced danceable rhythms in homes that had acquired phonographs, recalibrating through technology the balance of recorded to live vocals, of Turkish to Ladino lyrics, of dancing to sitting, for a lively night of partying.

What did this phonograph culture, specifically its technology and equipment, look like in Seattle Sephardic households, offering, as RCA Victor put it in a promotional film, “the music people want when they want it”?

Early recordings at the tail end of the nineteenth century were imprinted on wax cylinders, but within the first decade of the twentieth century, shellac 78 rpm discs replaced wax cylinders. Gramophones – the equipment with which to play the discs – flaunted horns to amplify the sound – horns that were soon reduced in size for some models and folded down for concealment within a cabinet.

1920s Ladino advertisement for a phonograph. Printed in La Amerika, the most important Ladino newspaper in New York (Courtesy Henry Benezra via Al Maimon, ST01963).

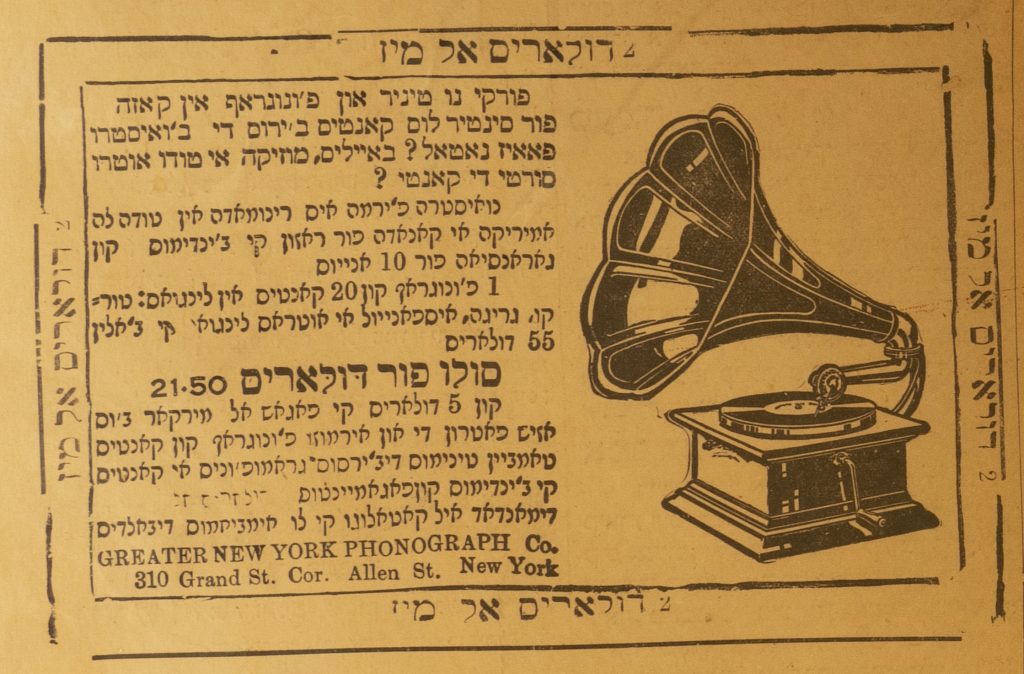

Ladino advertisement for an upscale phonograph from Livro de Embezar las linguas Ingleza i Yudish (1916). In this period phonographs as an enhancement to home decor were sold alongside items like sofas, lamps, and clocks in houseware stores in New York, Istanbul, and other major cities (ST0007, courtesy Isaac Azose).

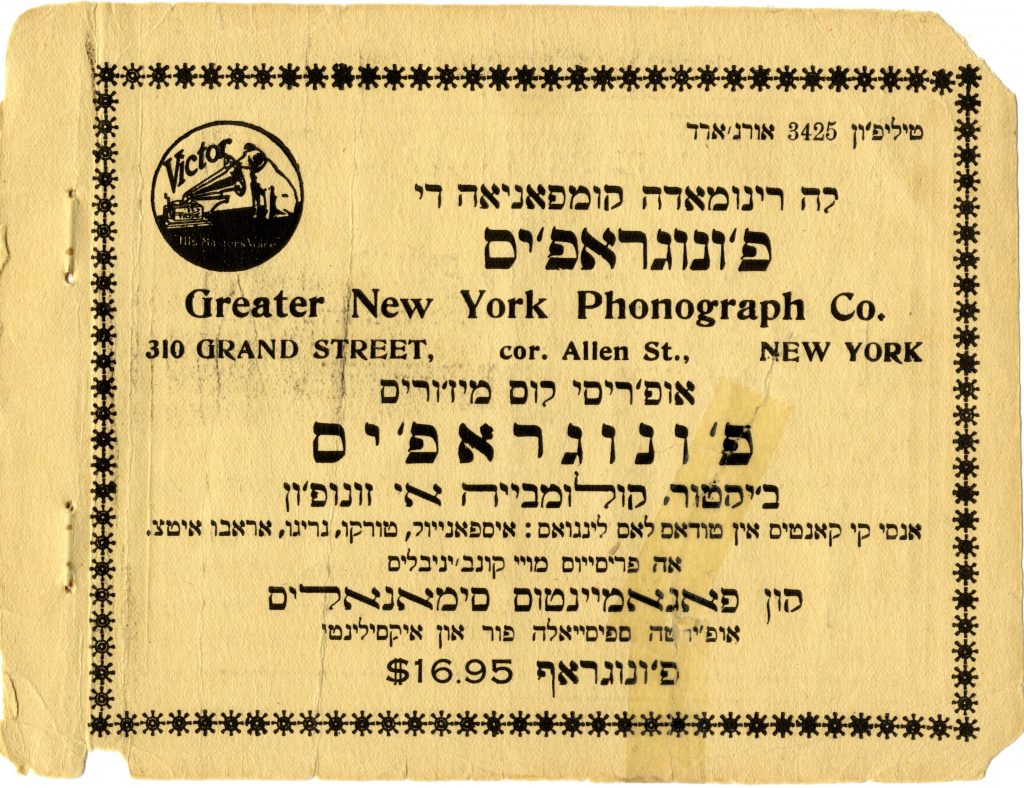

Ladino-English phonograph advertisement from Livro de Embezar las linguas Ingleza i Yudish, a Ladino guidebook for immigrants to the United States (ST0007, courtesy Isaac Azose).

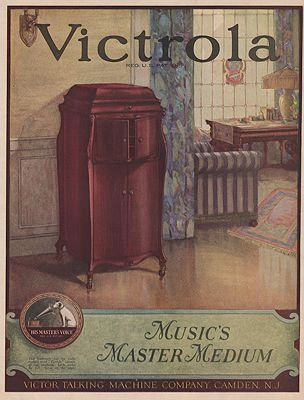

In the early years of the industry record companies pursued high record sales in order to sell gramophones, some of which served as luxury pieces of furniture for those who could afford them. “You wouldn’t know what it was,” one woman proclaimed as she described the Victrola in the home of her mother’s cousin. Made of dark wood with legs, it stood comfortably and decoratively among other furniture in the living room, its equipment hidden under a lid, and records stored behind a cabinet door. Next to a plant stand displaying a “healthy and happy fern,” the Victrola seemed more like a showpiece. “We imagined people with Victrolas were really ‘up there,’” she reflected. “Rich – like people living in brick houses.”

Advertisement for Victrola phonograph (magazine not known, 1923). Victrolas were manufactured and sold in a variety of models c. 1906-1925. Collection of the author.

To be sure, differences in phonograph models often signaled disparities in income among Sephardic neighbors. Advertisements for gramophones-as-furniture typically elaborated on how the equipment would enhance well-to-do living room décor rather than extolling their novel musical technology. Hiding the machinery boosted the visual impression of a multi-purpose wooden cabinet, and sometimes, like the remembered deluxe Victrola, the phonograph was rarely, if ever, used.

With the expanded record market of the 1920s consumers of modest means as well as cafés, bars, and worksites could own record players. Isaac Azose, hazzan (cantor) emeritus of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth whose musical parents Jack and Louise hosted parties, remembers the simple, small record player they used for nochadas in the 1930s – it was less fancy than some, but still stood on legs with a hood covering the turntable.

Another family purchased their equipment later, when television emerged after World War II, pooling their money to buy a Sylvania combo phonograph/radio/TV console. “The blond wood contrasted with the dark wood of our William and Mary furniture,” they noted. By the post-war second generation of Seattle Sepharadim, record playing equipment had lengthened to accommodate new technologies, while conserving their dual purpose as music source and furniture.