Ashley Bobman discusses her great-grandfather’s notebook with Prof. Devin Naar, who is supervising her exploration of Ladino and Sephardic history.

Like most good stories, this one is about luck and timing.

In 2011, the Sephardic Studies Initiative at the University of Washington acquired four notebooks, ranging from 40 to 400 pages, belonging to the Sephardic cultural activist Albert D. Levy (1896-1963). These notebooks are full of writings in Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, the language spoken by Jews whose ancestors fled Spain and Portugal and settled in the lands of the Ottoman Empire. Like many of the rare Ladino documents being preserved, archived, and studied at the UW, the Levy journals are completely unique, and they have never been translated into English — until now.

And here’s the twist: the person doing this painstaking work of translation is Levy’s own great-granddaughter, Ashley Bobman.

How did this come about? At a Hillel Shabbat dinner in the autumn of 2012, members of the Jewish Studies faculty were meeting students and sharing about their courses and research. Bobman, a freshman taking pre-nursing courses, happened to sit near Prof. Devin Naar, who runs the Sephardic Studies Initiative, and Lauren Spokane, Assistant Director of the Stroum Jewish Studies Program. As they began chatting, Bobman revealed that her family on her mother’s side was Sephardic. Prof. Naar asked about her mother’s maiden name. When she said Levy, a light bulb went off in the historian’s head: Levy was also the name on the four Ladino notebooks that had recently been lent to his archive.

“Do you happen to be related to an Albert Levy?” Naar asked excitedly. When Ashley Bobman confirmed that Levy was her mother’s grandfather, Naar knew he was sitting next to the great-granddaughter of one of the leading Ladino writers of the twentieth century.

A prolific journalist, educator, and community leader, Albert Levy was born in 1896 in Salonika, a major port city then part of the Ottoman Empire. There he edited El Liberal, a Ladino political daily, and was a teacher. In 1916, to avoid military service recently implemented by the new Greek state, which now controlled Salonika, Levy immigrated to America. He lived on New York’s Lower East Side, where he was involved with several Ladino publications including El Kirbach Americano, El Proletario, and El Luzero Sefaradi. Levy’s most significant contribution to the American Ladino press was his leadership of La Vara, which he founded in 1922. La Vara was the last Ladino newspaper published in Hebrew letters anywhere in the world; it folded in 1948.

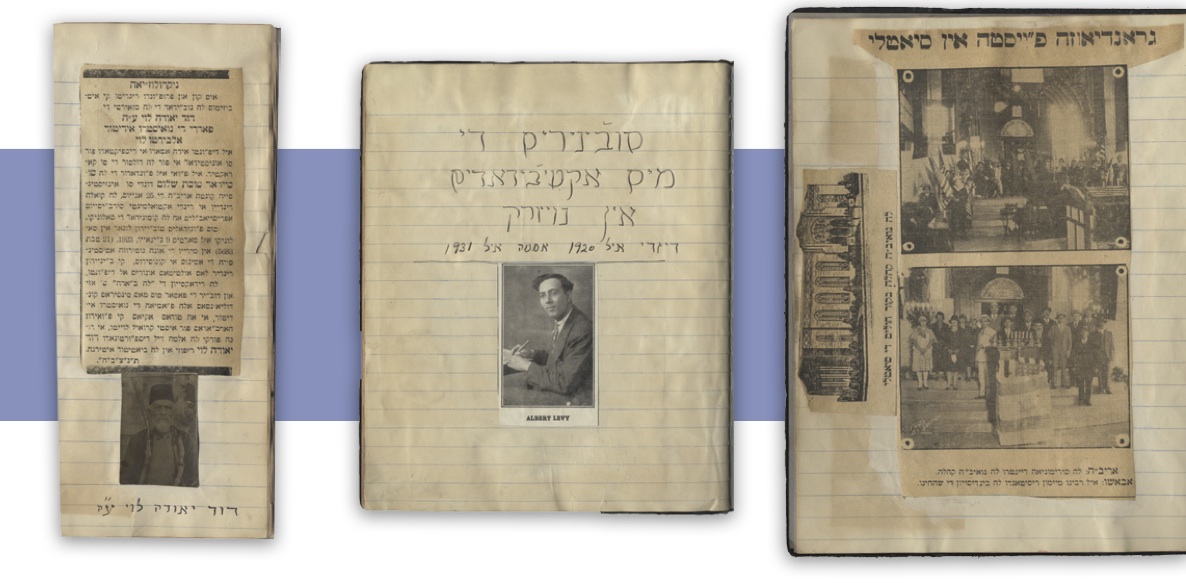

Left: An obituary for Albert Levy’s father, David Judah (Yeuda), who died in Salonika in 1923. The obituary appeared in La Vara, the Ladino newspaper published by Levy in New York. Middle: Handwritten Ladino title page of one of Albert Levy’s notebooks, which reads, “Souvenirs of My Activities in New York, 1920-1931.” Right: “A Grand Fiesta in Seattle!” Photographs of the inauguration of Sephardic Bikur Holim synagogue in Seattle. The picture of community members includes Rabbi Abraham Maimon. Published in La Vara in New York, ca. 1928.

Albert Levy’s cultural activism gained him a national and international reputation as a teacher and community leader. In the early 1930s, when the Sephardic synagogues in Seattle, especially Sephardic Bikur Holim, decided to establish a local Sephardic Talmud Torah (Jewish school), they recruited Levy to be the director. Relocating from New York to Seattle, Levy continued contributing his writing and oratorical skills to Sephardic cultural organizations. He even became involved in the nascent American Hebrew movement, writing for HaDoar, a Hebrew magazine. Levy died in 1963, leaving behind a legacy of tireless Sephardic cultural activity; in addition, he and his wife Lucy had three children, eight grandchildren, and eventually seven great-grandchildren.

“Albert Levy was likely the most prolific Ladino journalist and author in the United States, and one of the most important international voices of Sephardic Jewry during the first half of the twentieth century,” reflected Prof. Naar, who is the Marsha and Jay Glazer Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and Assistant Professor of History at UW. “The opportunity to bring his writings to life and to recreate his cultural milieu — all possible through these notebooks — is both rare and exciting.” The notebooks, which contain clippings of many of Levy’s published essays and poems, are on loan from Sephardic Bikur Holim, thanks to community leaders Lily DeJaen and Al Maimon, a member of the Stroum Jewish Studies Program’s Advisory Board and its Sephardic Studies Committee.

After that fateful meeting at Hillel, Ashley Bobman made arrangements to spend Winter Quarter working with Prof. Naar on an experiential learning project for the Interdisciplinary Honors Program. Helped by her knowledge of the Hebrew alphabet and Spanish, she picked up the Ladino language rather quickly; in fact, she describes herself as “pleasantly surprised” by the progress she made. She translated a range of Levy’s works, from an overtly political poem about the impact of the Spanish Inquisition, to more personal texts, such as obituaries Levy wrote about his Salonikan family. So thoroughly did Bobman enjoy this learning experience that she signed up to continue the independent study in the Spring Quarter.

As anyone who has ever tried to work between two (or in this case, three) languages knows, the translation process is time-consuming but rewarding. Bobman first transliterates every Ladino word from Hebrew letters into Latin letters and then begins her translation; next she consults a Ladino-English dictionary and uses contextual clues to put full verses or sentences together. At her regular meetings with Prof. Naar, they go over her drafts line by line, and he offers suggestions for how to polish and refine. He also helps her survey the contents of the notebooks and select which text to try next. Bobman is currently working on a text about the history of the Jews of Salonika, written in poetic verse.

Even more exciting than grasping the mechanics of how Levy wrote, though, is understanding what he wrote — the actual meaning and impact of his writings. Bobman explains, “I knew from my family that he had done a lot of writing and worked for newspapers, but I am only just beginning to understand the contributions he made to the Sephardic community.” As she worked through the texts, she began to notice certain themes and motifs that repeat in Levy’s oeuvre, such as the need to unite the Sephardic community. Thus a picture began to emerge of her great-grandfather’s core values; she started to understand who he was and what he stood for.

“For me it’s a great opportunity to get to know my great-grandfather Albert’s work and learn about my family’s background,” Bobman says. A native of Seattle, she is the daughter of Bruce Bobman and Karen Tacher-Bobman, whose parents were the late Rachel (Levy) and Jack Tacher. Bobman’s older brother Jacob graduated UW in the class of 2011; he earned a Jewish Studies minor (and was featured in our Fall 2011 newsletter). The whole family gets regular updates on the Levy notebook project. Bobman says proudly, “I share my translations with my siblings and parents, so they can learn about what Albert Levy was doing. My mom reads a lot of my translations, and she is really glad I am doing this work.”

Thanks to a chance meeting at UW Hillel, the curiosity of a Jewish Studies professor, and the dedication of a talented student, Albert Levy’s work will be accessible to a whole new generation.

Ashley Bobman plans to continue working on the Albert Levy notebooks throughout her time at UW and has specific learning goals for herself. Although she has made extraordinary progress in two quarters, she says, “I still have much to learn about the language that my ancestors spoke.” Currently, she is limited to working on texts written with the standard Hebrew alphabet, but the notebooks also contain materials written in Rashi script, or rabbinic type, and soletreo, the Sephardic cursive handwriting.. She is working on learning these characters so she can access more of Levy’s works.

As Bobman notes, the project has connected her with her family as well as her community: “This engagement provided me with an opportunity to learn more about my Sephardic heritage and allowed me to become involved in the Sephardic Studies Initiative.” All of her translations will eventually become part of the online Ladino library being developed by the Sephardic Studies Initiative at UW — the first library of this kind in the world. Her work will be a resource that others can study in the future to understand this key figure in American Sephardic history, and Sephardic culture worldwide.

“Ashley’s contribution to the Sephardic Studies Initiative is absolutely invaluable,” commented Prof. Naar. “She continues to immerse herself in her great-grandfather’s sophisticated writings, which deal with politics, community, identity, history, and morality — and were largely composed in poetic verse. Bringing together her knowledge of Hebrew and Spanish, she immediately picked up the methods of transliteration; her vocabulary and confidence improve every week, as does her familiarity with the history, culture and language of her ancestors here in Seattle, in Salonika and in Spain. She has far exceeded my expectations and I am thrilled to be working with her.”

During six decades of cultural activism that began in Salonika and zigzagged across the United States, there was one constant in Albert Levy’s career: an eagerness to share his love of Sephardic history with dispersed Ladino-reading audiences around the world. Now, thanks to a chance meeting at UW Hillel, the curiosity of a Jewish Studies professor, and the dedication of a talented student, Levy’s work will be accessible both in Ladino and in translation to a whole new generation. Quite fittingly, Ashley Bobman is now fulfilling the very same cultural goals as her dynamic great-grandfather. I think it’s fair to call this a case of kismet.

All these writings are scholarly works that deserve to be shared with the whole world. Thank you for preserving them and translating them for those of us who are not familiar with Ladino. My interest is in the differences between Old Castillian Old Ladino and the Modern Spanish and Ladino. How are these languages related and when and how did they become different languages?