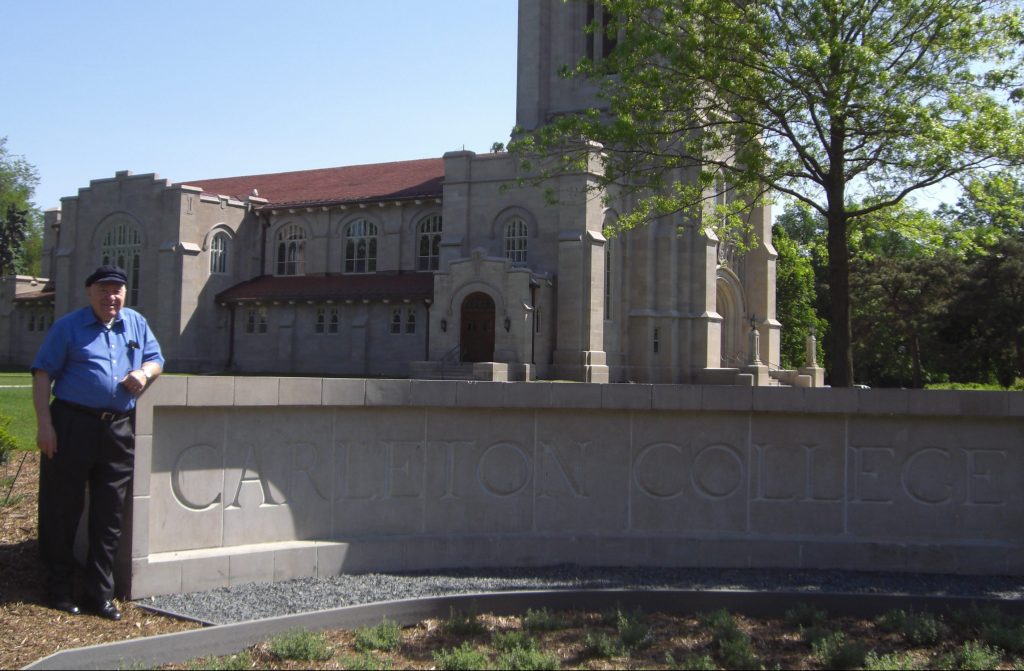

Isaac Azose on the Carleton campus

By Dr. Maureen Jackson

The Athenaeum, a hall on the main floor of Gould Library, filled to capacity, as students, faculty, and community members wandered in to hear Isaac Azose speak and sing. A retired hazzan (cantor) of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, Isaac had just flown into Northfield, Minnesota from Seattle to participate in the “Symposium on Sephardic Cultures & Legacies: Jews from Spain, Turkey, and Morocco” at Carleton College (May 14-16, 2012). Sponsored by Judaic Studies, Middle Eastern Languages, and the Viz Initiative (Visualizing the Liberal Arts Grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation), the event showcased both Isaac Azose and the Moroccan Jewish writer, Esther Bendahan, who had flown in from Madrid. “Are your students really going to be interested in how I use Ladino in our prayer services in Seattle?” Isaac asked me anxiously, as we explored topics a few weeks earlier for his lecture-demo. The co-organizers of the symposium were likewise worried, asking “How much publicity have you done, Maureen?” and suggesting a multitude of list serves and calendars and student groups to contact for his talk.

Indeed, Northfield demographics and Carleton course offerings were hardly plentiful in things Sephardic. Was my own confidence (‘when he sings they will come’) unfounded and a bit reckless? I began to wonder. In the end the crowd was plentiful and deliciously varied. Not only did Carleton faculty – in French, Spanish, Arabic, Hebrew, and Religion – attend, but also a University of Minnesota Spanish professor drove down from the Twin Cities (Minneapolis/St Paul, about 50 miles north) and the part-time rabbi on campus postponed her Torah study session so that she and her students could attend. Music, history, and international studies majors – from freshmen to seniors – came. As the post-talk Q&A revealed, most were present to learn about a language, history, music and person they knew practically nothing about.

Sign orienting visitors to Northfield, Minnesota.

The town of Northfield, which I called home for two years (2010-2012) as the ACLS New Faculty Fellow at Carleton College, is a small (pop. 20,000) Midwestern mill town located on the meandering Cannon River and known for its two liberal arts colleges, Carleton and St. Olaf’s. Although there is a new Beit Midrash (House of Study) on the main street, Jewish residents who attend synagogue generally drive up to the Twin Cities. Historically, Minnesota and the Dakotas attracted relatively large numbers of Jewish immigrants during the waves of immigration from Europe and Russia to the U.S. in the second half of the nineteenth century. Minneapolis and St Paul currently support over fifteen synagogues, several kosher bakeries and grocery stores as well as the Minnesota Jewish Theatre Company. When I first invited Isaac to the symposium, a main concern was making sure that he and his wife Elisa could keep kosher during their residency. With the resources in the Twin Cities and the help of a kosher-keeping colleague and her ice chest, we were able to transport sufficient amounts of kosher food into Northfield for my guests.

During his lecture-demo in the Athenaeum, Isaac Azose sang his way through a multitude of prayers to show how he adapts Ladino songs to Hebrew scripture during Shabbat and holiday services. Beginning with the Kedusha from the Amidah of the Musaf service of Shabbat, Isaac sang the Ladino songs “Povereta Muchachica” (Poor Little Girl), “Mama Yo No Tengo Visto” (Mama I Have Not Yet Seen) and “Avreh Este Abajour Bijou” (Open Your Shade, My Jewel) before each section of the Kedusha, delivering the Hebrew prayers after each song in his warm and vibrant voice. The final section of the Kedusha was adapted to the Israeli folksong by Naomi Shemer, “Yerushalayim Shel Zahav” (Jerusalem of Gold). Isaac also shared liturgical prayers spoken or sung in Ladino during holidays, for example, the final “Ayom Arat Olam” or “Oy se krio, el mundo” in Ladino (Today, the World Came Into Being) on Rosh Ashana, and “Ken Supiense I Entendiense” (Who would know and who would understand) at the end of the Passover seder. Explaining a felt need for a distinctively Sephardic Birkat Ammazon (the Blessing After Meals), Isaac sang the adaptation that Samuel Benaroya (1908-2003), who had served as hazzan of Sephardic Bikur Holim in Seattle, made in 1972 to the tune of a Turkish march.

Watch Isaac Azose sing “Avreh Este Abajour Bijou” and “Mama Yo No Tengo Visto” in these video clips, courtesy of the Department of Middle Eastern Languages, Carleton College:

Through their musical adaptations of Hebrew texts to Ladino, Israeli and Turkish songs, both hazzanim, Azose and Benaroya, participate in the historical, ubiquitous and creative borrowing of diverse music in the production of new pieces. Termed ‘contrafacta’ by musicologists, such adaptations are found, studied and performed in a variety of locales by musicians the world over. The local, changing and malleable nature of musical forms, in fact, makes a myth of past assumptions that, based on textual continuities, Sephardic Jews preserved Ladino romansas (ballads) in their pure form from 15th century Spain through to the present day. In fact, through a process not unlike Isaac’s, Jews often adapted song lyrics to local melodies (Balkan, Turkish, Arabic, for example), depending upon their settlement patterns in the Ottoman empire and Turkey, and these melodies in turn changed over time.

In the case of liturgical music, Ottoman and Turkish Jews participated in the Ottoman system of makams (modes) while singing prayers in synagogues and developed a paraliturgical repertoire, the Maftirim, that translated the Ottoman court suite into Jewish religious space – a repertoire full of both original compositions and adaptations from non-Jewish Ottoman composers. Rabbinical judgments against the religious use of music considered non-Jewish varied across time and place; some feared, for example, that congregants would be distracted by the original Ladino love song, rather than focusing on the Hebrew prayer. However, evidence shows that in practice, music and audience preferences generally won out over rabbinical considerations. Even so, A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica, the newly published memoir of Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi (co-edited by former UW professor Sarah Abrevaya Stein), elucidates the travails of a Jewish musician who was repeatedly excommunicated for adapting Hebrew prayers to local ‘alaturka’ musical forms in mid-19th-century Salonica.

The Carleton crowd was delighted to hear Isaac recite the poetry of a Ladino love song, then seamlessly fit a Hebrew prayer to the same melody. “How wonderful to hear the cantor today! A real delight!” exclaimed Rav Shosh, the part-time rabbi at Carleton. “When Azose knowledgably spoke about ballads and his profession as hazzan,” offered one student, “I realized how talented he was in adapting the past traditions to present tunes.” Another focused on language: “Azose has proved it possible to continue, at least to some extent, the use of Ladino in both music and conversation.” At the end of his talk, Isaac shared a recent example of a youth adapting a Hebrew prayer to contemporary American music. One Saturday, his son Yossi was leading the Musaf service at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth. As Isaac sat behind his son at the Tevah (Reading Desk), he was shocked to hear the theme song from The Godfather as his son began to sing the Hebrew words of the Keddusha, an important part of the Musaf prayer. After his consternation wore off, Isaac realized – as did most of the other congregants – that the adaptation worked beautifully musically – and that’s what counted.

Isaac Azose specializes in the unique Sephardic liturgies of Turkey and Rhodes, as practiced in Seattle, Washington. He has published Sabbath and holiday prayer books to document both traditions and produced a CD of the liturgical music of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, where he served as hazzan for over three decades. He has also released a 2-CD set of Ladino songs, Ladino Reflections. For further information, see: https://www.isaacazose.com/

Isaac Azose specializes in the unique Sephardic liturgies of Turkey and Rhodes, as practiced in Seattle, Washington. He has published Sabbath and holiday prayer books to document both traditions and produced a CD of the liturgical music of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, where he served as hazzan for over three decades. He has also released a 2-CD set of Ladino songs, Ladino Reflections. For further information, see: https://www.isaacazose.com/

Maureen Jackson received her PhD at the University of Washington and served as the Hazel D. Cole Fellow in the Samuel & Althea Stroum Jewish Studies Program in 2008-2009. She is currently a Harry Starr Fellow at Harvard University. Her first book, Mixing Musics: Turkish Jewry and the Urban Landscape of a Sacred Song, is forthcoming in June from Stanford University Press.

Maureen Jackson received her PhD at the University of Washington and served as the Hazel D. Cole Fellow in the Samuel & Althea Stroum Jewish Studies Program in 2008-2009. She is currently a Harry Starr Fellow at Harvard University. Her first book, Mixing Musics: Turkish Jewry and the Urban Landscape of a Sacred Song, is forthcoming in June from Stanford University Press.