An AP photo from June 1939 shows German Jewish refugees returning to Belgium after being denied entry to Cuba and the US.

By Michael Rosenthal

This past February I read an article on the BBC website reporting that some onlookers had cheered as a fire burned down a shelter for migrants in Bautzen, Germany. While this incident was appalling in itself, it also had special resonance for me, as my father was born in Bautzen and had been forced out of Germany not long before the Second World War. Unlike many other members of his family, he and his parents survived the Holocaust because they were able to get visas into Colombia; the US was closed to them already.

Was this 2016 arson incident similar to what had happened in 1938 when synagogues were burned, businesses destroyed, and Jews driven out of the towns in which they lived? Or was the persecution of a minority that had lived there for hundreds of years something different altogether?

It is surely a mistake to assume that one event has the same cause of another one eighty years ago, even if they resemble one another. On the other hand, to understand an event does not only mean looking at the set of its immediate or proximate causes; it also means to look for patterns and structures that give it meaning. It is clear to me that the response of many people in Germany, including its government, to the current immigration crisis is being shaped, whether consciously or not, by its past. When Angela Merkel took the political risk to admit a million refugees into Germany she was mindful—along with millions of citizens—that postwar Germany has thrived precisely because it has rejected the chauvinist and xenophobic political forces that led it into a disastrous war more than seventy years ago.

The same is true, I think, of our discussion in the United States. We could think of our debates over Syrian refugees or Mexican immigrants as unique cases, and in some senses they are. On the other hand, it is difficult to exclude our personal and collective histories from the debate. When I think of Syrian refugees it is hard for me, at least, not to think of my father’s family being barred from the United States just when they needed the refuge the most. Likewise, when I think of Mexican migrants, it is hard not to think of my father and his family coming to Los Angeles later after the war to seek opportunity. Were they so different in this regard from the landless peasant in Oaxaca who makes the perilous journey north? I am certainly not the only one who believes that our historical experience should inform our contemporary policies.

Viewing the Immigration Debates in Historical Context

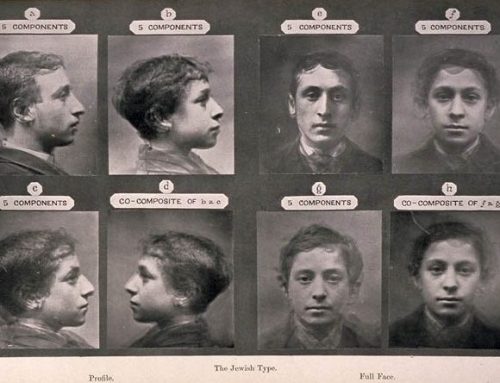

If we look at the situation from a scholarly perspective, it is impossible not to consider the history of debates over immigration that go back to the nineteenth century. Many people were opposed to allowing Catholics—Irish, Polish, and Italian—to enter the US, in part on religious grounds. And can we really understand the issue of Mexican migration without looking at the long history of disputes over the border and colonialism in the Southwest? Moreover, the terrible legacy of slavery and racism casts a shadow over all our political debates, much like the Holocaust does still in many parts of Europe.

If we pose the question in the starkest form—should the United States (or any other country, for that matter) discriminate among potential immigrants on the basis of religion?—the answer is really crystal clear to me. It is “no.” Whether we look directly at our Constitution, which promises religious freedom in the first amendment; or to the history of our country, which was founded in part as a refuge for those who had been religiously persecuted and subsequently absorbed millions of people of all faiths and backgrounds; or to the liberal principles that underlie our government, which to use one prominent example from the Anglo-American philosophical tradition, John Rawls, demand that we set aside the contingent features of our identities (such as gender, economic class, or religious beliefs) when we determine the fundamental principles of justice—all of these reveal a fundamental American imperative not to discriminate on the basis of religion.

It would be easy, then, to dismiss the opposition to allowing mass immigration of Muslims from Syria, for instance, since it appears based on some form of prejudice that is contrary to our highest principles. Too easy, in fact. Just as it is important to look at the nuances of the historical question about immigration—to see the deep layers of the past involved in the response of the present—so too must we consider the question whether there are principles that might justify excluding immigrants from our shores. If we are to get beyond moralizing about the situation and try to understand what is truly at stake, then it is important to recognize that those who oppose allowing the mass immigration of people who are different ethnically and religiously from those who are currently the majority in a country might have some legitimate reasons.

The key to understanding this opposition is, I believe, the very nature of the modern nation state. On the one hand, it is what Germans call a Rechtsstaat, an entity determined by law and the principles that found the state. For us, this is the US Constitution, and it sets out the ideals by which we ought to live. On the other hand, the state is also a nation, that is, it incorporates various key aspects of people’s contingent identities into its very definition. In Europe this often means incorporating ethnic, linguistic, and religious features into the state’s basic principles. Thus, for instance, the British included what appear to us as antiquated forms of government into their system—monarchy and aristocracy—as well as dominant religious institutions. As a result there is a Queen, who is head of the government and head of the official Church of England. In Germany, after the second World War, the government accepted German-speaking refugees into the new German state at least partly on the ground that they belonged to the nation, even if they had never actually lived in that particular state.

Moreover, nation states are not wholly abstract entities, but almost always extend over a particular physical territory, which means that they have boundaries and borders that are also part of people’s political identities. We think that it is legitimate for the state to exert control over its territory.

It is not always simple to disentangle these two aspects of our nation. For instance, even though our Founders rejected the idea of an official religion, the paradoxical effect of this freedom has been, as Alex de Toqueville noted back in the nineteenth century, that American politics is more deeply influenced by religion than in those countries where religion is officially part of the state. Without the control of a central state church, religion has thrived in the US in a variety of forms. Sometimes religion can lead to bigotry and prejudice, but it can also express and support some of our highest moral ideals. It is inevitable that the freedom to live according to our religious beliefs will be expressed in our democratic politics. It may be that the formal features of the constitutional state need to be invoked to limit the excesses of this democratic impulse to translate religion into politics, but we ought not to simply dismiss all efforts of religious groups to influence the state as illegitimate.

The Sometimes Slippery Goal of Integration

When we discuss immigration, we also need to make two further sets of distinctions. The first has to do with the category in which we place immigrants, who are not all the same. The terminological distinctions between “refugee,” “economic migrant,” “asylum seeker,” etc. are important: they form different legal and sociological categories that often have important practical and moral consequences. However, they are not always easy to make. If a Syrian doctor or shopkeeper, for instance, has lost the ability to practice his or her profession in their native land, due to ongoing civil war, or if a woman does not have access to the same educational opportunities as a man, or if members of a religious minority are restricted in what professions they can pursue, and then decide to leave to seek opportunities elsewhere, then are these political refugees or economic migrants?

Syrian and Iraqi refugees are greeted by Spanish volunteers as they arrive at the island of Lesbos, Greece. October 30, 2015. Photo by Ggia via Wikimedia Commons.

Drawing again from my own story: my father and his family were economic refugees to the US from Colombia in 1947, but on the other hand, they were seeking opportunity because of dire political and religious persecution that culminated in their exit from Germany in 1939. The legal categories are important, but they are not always clear when we examine the particular situation in any depth or historical breadth.

Secondly, we need to distinguish the reasons for letting someone into our country from the difficulties that may arise once they get here. How does a new immigrant become one of “us”? Not surprisingly, religion is often quickly tied to these questions. However, the debates around “integration” also are notoriously difficult to delineate because what counts as integration—who is a social insider versus an outsider—can be very difficult to determine. The legal and sociological mechanisms of integration vary from place to place and over time.

There are myriad examples of people citing lack of integration as a reason to prevent immigration at all. In Austria immigrants from Syria are faulted for their lack of punktlichkeit or punctuality. In Denmark there is the familiar refrain that the newcomers have not learned the majority language (Danish) quickly enough. In the US, we find many of the same kind of complaints, regarding ways of life, culture, language, and religion. Second and even third generations of immigrants are not always, apparently, successfully “integrated.” We could point to the children of African immigrants in the banlieues

But what marks “integration” and how long should it take newcomers to achieve this goal? We must remember that it took a few generations for European immigrants to the US to stop speaking their native languages in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Montana, let alone the streets of New York. And whose fault is it when integration is not achieved smoothly? Most importantly, who gets to determine the timeframe and standards of successful integration?

When it comes to religion, why should a country, whose founders conceived it as a place of freedom, proclaim that continued adherence to a particular religion and lack of integration to the beliefs of the majority is a reason to deny entrance? On the other hand, do our ideals require that religion transform itself in order to meet the criteria of proper citizenship? Are there aspects of some religions that are incompatible with our constitutional principles and historical identity as a nation? In this respect the problem of the integration of immigrants once again reflects the deepest tensions within our nation state.

Jews have taken a variety of paths in their journey as immigrants to the United States. Some have remained stubbornly faithful to the folkways and religious beliefs that they imported with them from abroad. Others have abandoned their religious practice and sought to assimilate as quickly as possible. In recent decades the increasing tolerance of American society towards Jews has speeded this process considerably with intermarriage and secularization taking a toll. (Of course there are several other paths as well.) How can we use our own historical experiences to help us make sense of the current immigration crisis?

I think that our task at the university is to both clarify and complicate the matter. We need to help others recognize that the moral and legal principles of our country are clear and ought to guide us, even and perhaps most especially during a crisis. At the same time, we need to point out the complications, historical and ethical, in the current situation. I have a sketched a few of these issues here, but I have only scratched the surface. We need to hear from thoughtful and knowledgeable people about the largest immigration crisis since the end of World War II.

It is to that end that I have organized a panel on “Immigration, Religion, and Human Rights” on Thursday evening, October 27th, at 7pm in the HUB. I have invited two philosophers, a sociologist, and a historian to offer a variety of perspectives on this topic. More information on the surrounding conference at the Simpson Center for the Humanities is available here. Whether you agree or not with what I have said in this article, if you find at least some of these questions interesting and important, then I hope that you will join us.

Michael Rosenthal is the Samuel and Althea Stroum Chair in Jewish Studies. He teaches and publishes in the areas of early modern philosophy, ethics, political philosophy, and Jewish philosophy. His current research focuses on the philosophy of Benedict Spinoza.

Michael Rosenthal is the Samuel and Althea Stroum Chair in Jewish Studies. He teaches and publishes in the areas of early modern philosophy, ethics, political philosophy, and Jewish philosophy. His current research focuses on the philosophy of Benedict Spinoza.

Leave A Comment