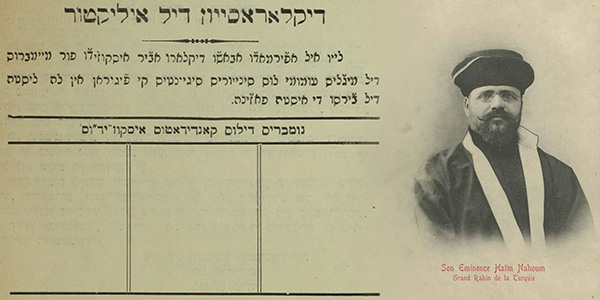

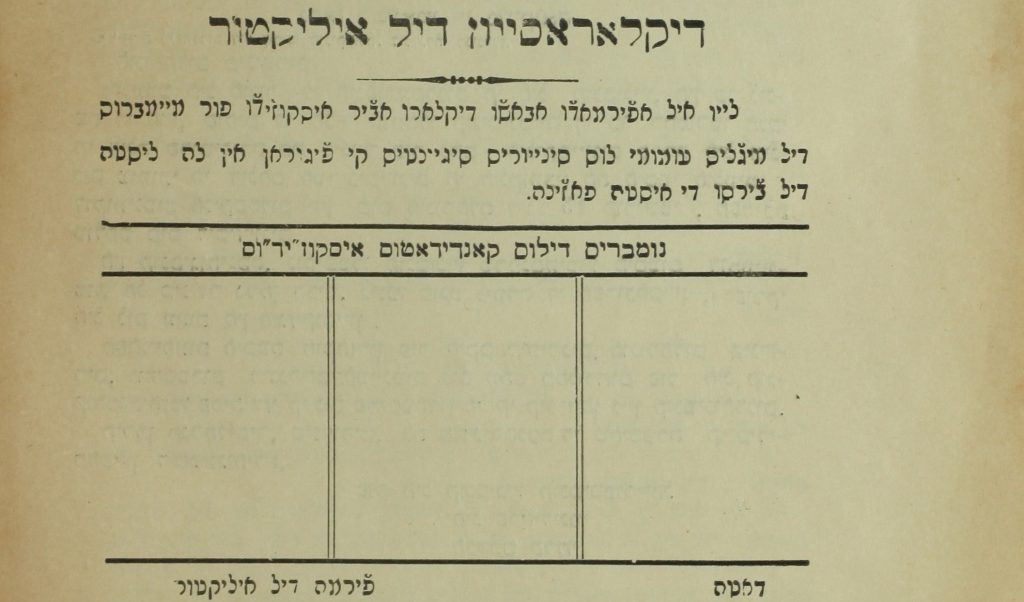

Left: Blank ballot for electing members to medjlis umumi. (ST00472, courtesy Richard Adatto) Right: Postcard portrait of Haim Nahum in traditional dress. (Public domain)

By Makena Mezistrano

Using artifacts from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, ‘From the Collection’ introduces the people, places, customs, and ideas that shaped the experiences of Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire, the United States, and beyond. Keep up with ‘From the Collection’ by subscribing to the Sephardic Studies Program newsletter.

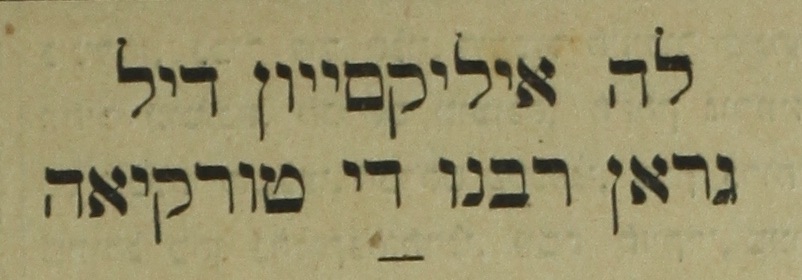

Having just lived through an unforgettable United States presidential election, I was drawn to the following headline in El Tiempo, Istanbul’s leading Ladino newspaper: la eleksion del gran rabino de Turkia.

El Tiempo headline announcing the election process for a new hahambashi, or chief rabbi, of the Ottoman Empire. (ST01103, courtesy Richard Adatto)

Though buried on the fifth page of the December 28, 1908 issue of the paper — relegated to second place behind the latest developments in Ottoman politics — the election of a new chief rabbi, also known as hahambashi (a combination of the Hebrew title for rabbis used by Sepharadim, hakham, and the Turkish başi, meaning “head”), became front page news within a year. On January 25, 1909 the lead story in El Tiempo, which spanned across half the issue, announced Haim Nahum as the new official representative of Ottoman Jewry. For the first time in the history of the position, the elected hahambashi would not only be a religious figure, but a diplomatic one as well.

Electing a chief rabbi

Beyond the political dimension of his position, Nahum was an unprecedented choice. Unlike the acting chief rabbis before him, Nahum was educated in the French-Jewish school system of the Alliance Israélite Universelle and ordained in Paris. His tenure as hahambashi coincided with the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, which rendered non-Muslims equal under the law and also brought increased freedom of the press — a shift that placed religious and political leaders under more public scrutiny than ever before. Throughout his tenure Nahum’s name frequently appeared in the local Jewish press: editors were embroiled in fierce debates over his often critical attitudes toward Zionism; some articles even resulted in public defamation lawsuits between journalists.

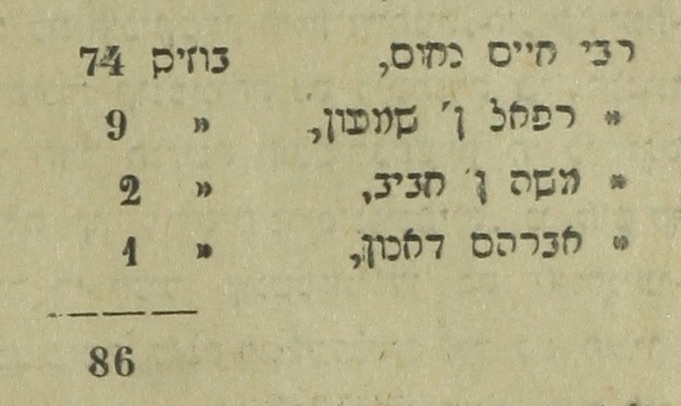

Vote tallies from the January 25, 1909 issue of El Tiempo showing Nahum’s victory in the race for chief rabbi. The last candidate on the list, Avraham Danon, was Nahum’s father-in-law. (ST01103, courtesy Richard Adatto)

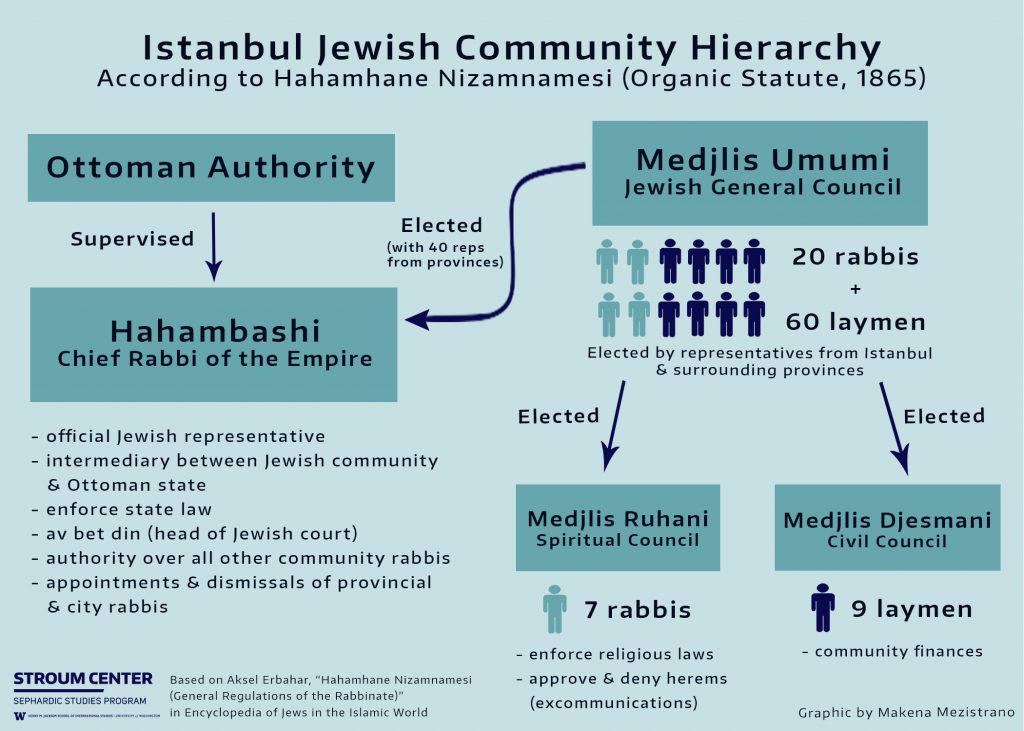

But the most noteworthy feature of Nahum’s appointment is the very word that drew me to the aforementioned headline in El Tiempo: eleksion, or election. Even though the office of the hahambashi had technically existed in the Ottoman Empire since 1835, Nahum was the first (and only) individual to be elected to this position by a representative committee known as the medjlis umumi — the Jewish general council of Istanbul — and its religious/spiritual arm, the medjlis ruhani.

The medjlis ruhani in particular was critical in the state’s aspiration to transform the hahambashi into more of a political role, and to diffuse the chief rabbi’s authority in Jewish law, or halakha, across the medjlis ruhani. The chief rabbi no longer had executive power to issue religious excommunications, or herems, without the approval of the medjlis ruhani; even when halakhic questions were submitted to the hahambashi, the spiritual council collectively undertook most of the research and then submitted its conclusions to the chief rabbi.

A representative Jewish election committee

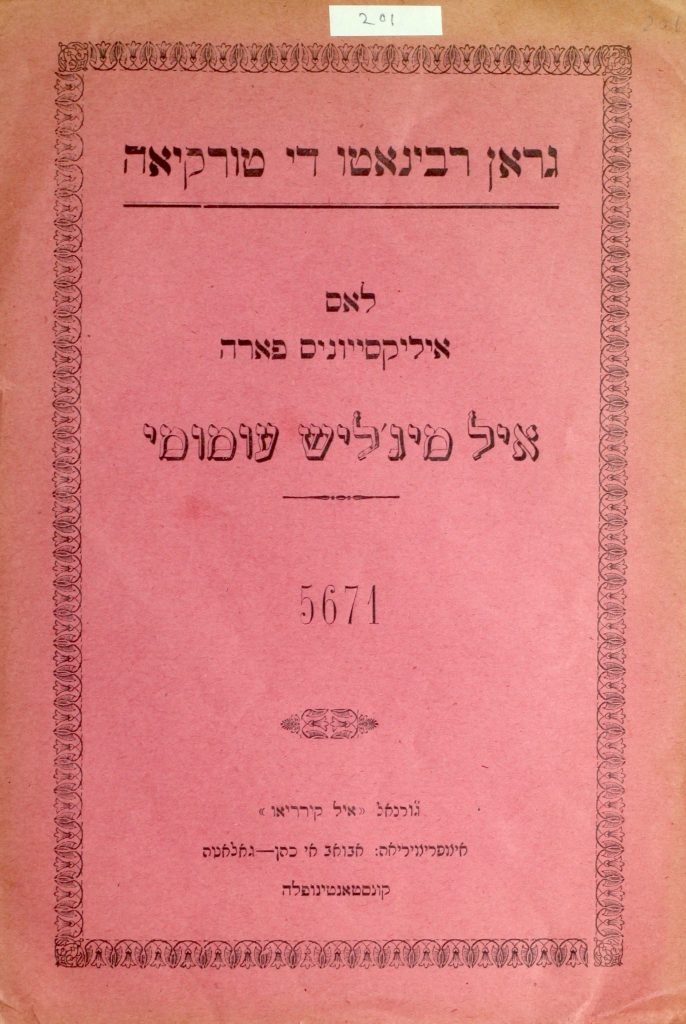

Las eleksiones para el medjlis umumi — a small, pink booklet published in Istanbul in 1910 that wound up in Seattle — reveals more about these community councils.

Cover of Las eleksiones para el medjlis umumi, a booklet of bylaws and reports for the Jewish communal council of Istanbul. (ST00472, courtesy Richard Adatto)

Understanding the reports and bylaws in the booklet, and their implications, must be contextualized in terms of how these committees were formed. The medjlis umumi and its subdivisions, which, besides for the religious council, also included the medjlis djesmani (civil council), were part of a major shift in Jewish communal organization in the Ottoman Empire mandated by the state. Often referred to as an “organic statute” and known in Ottoman Turkish as Hahamhane Nizamnamesi (literally meaning “regulation of the rabbinate”), this top-down reform created a hierarchical structure for Istanbul’s Jewish community in 1865 (modeled on those created for Greeks and Armenians in 1862 and 1863, respectively).

Within this new structure, the hahambashi was still recognized by the sultan and served as the community’s primary interlocutor as he had since the position was created in 1835, but he now had to be elected by the medjlis umumi and the medjlis ruhani, along with forty additional representatives from outside the capital. While Nahum had authority over all of the empire’s Jews with this election, the specific hierarchies of the organic statute (outlined below) technically only applied in Istanbul. To be sure, similar Jewish governing committees were adopted in Salonica and Izmir, for instance, albeit with variant titles and areas of responsibility.

The medjlis umumi and its subdivisions provided Ottoman Jews with new avenues to explore and negotiate their place in the empire’s capital, some of which are illustrated in Las eleksiones. As a document that defines the qualities and characteristics of a representative body, Las eleksiones is a window into how Ottoman Jews conceptualized authority, citizenship, and Jewish representation at the turn of the twentieth century.

Engaging with state law

In a letter to the president of the civil council (medjlis djesmani) recorded in this booklet, the medjlis umumi reports that, with the right members elected to these committees, they will “raise the prestige of the Jewish nation in Turkey” (a relevar el prestidjio dela nasion Djudia en Turkia). They should be “the most notable members of the community” (los mas notavles del lugar). Only law abiding citizens — or, more literally, “not criminals” — are eligible candidates for the medjlis umumi (ke no fueron kondanados por krimen ni deleto). Some, but not all, must be well-versed in Jewish law, and fluent in Hebrew (i ke segun la ley algunos de entre eyos deven konoser el Ebreo).

What emerges as paramount, however, in “raising the prestige of the Jewish nation in Turkey,” is for committee members to play an active role in shaping how the state’s legal system was applied to the Jewish community. These Jewish representatives would not only be subjects of the developing Ottoman policies, but would have legitimate, public roles just like the empire’s other communities. To debate and analyze the application of state laws was also an essential exercising of their rights as citizens.

A sample election ballot for voting in members of the medjlis umumi. The Las eleksiones booklet includes detailed instructions for filling out and depositing these ballots, including how to fashion a ballot box (kasha kon burako; a box with a hole). (ST00472, courtesy Richard Adatto)

Fluency in Jewish affairs — and a Jewish language

A formal engagement with Ottoman diplomacy went hand-in-hand with fluency in internal Jewish affiars, as only those most up-to-date with communal activities were eligible for election onto the medjlis umumi — though it is unclear how their familiarity with these affairs was evaluated (ke son kuento es posivle al koriente delos echos dela nasion djudia). Furthermore, all members were required to be fluent in Ladino — identified here as Judezmo, the “Jewish language of the empire” (i ke saven avlar i eskrivir el djudezmo).

The language mandate is of particular importance in a document written in Istanbul in the early twentieth century, when many Jews were advocating for Ladino to be abandoned in favor of French or Turkish. The motivations behind these linguistic arguments varied, but some hinged on how Sepharadim presented themselves in the modern world: While Turkish could signal political allegiance and French could help fashion a European identity, Ottoman Jewish elite often portrayed the mixed linguistic influences of Ladino as a sign of its status as a “bastardized” “jargon” that revealed allegiance neither to the Ottoman state nor a European power.

Amidst these debates, the medjlis umumi required its members to speak a language that would certainly identify them as Jewish, and, in the context of a communal council created by the state, legitimized Ladino in a powerful way as the language of the Ottoman Jewish people. (As a sign of this legitimacy, and contrary to what some scholars have suggested, segments of the Hahamhane Nizamnamesi itself was published not only in Ottoman Turkish, French, and German, but also Ladino.)

The end of empire, the end of the medjlis umumi

Haim Nahum was the only hahambashi of the empire elected by the medjlis umumi. Intense opposition from growing Zionist organizations eventually led to his resignation in 1920, and Nahum moved to Cairo. Subsequently, the committee never conducted an election with the same rigor and process as Nahum’s. As new laws came into effect as the Ottoman Empire dissolved, and the new Republic of Turkey emerged, the medjlis umumi and its subdivisions eventually disbanded in 1926. Yet even with only one formal rabbinic election cycle to its credit, the medjlis umumi shaped how Jews in Istanbul — and the Ottoman Empire at large — navigated the intersections of authority, citizenship, and Jewish representation at the turn of the twentieth century.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Suggestions for further reading

Ịsmaịl Aydıngün and Esra Dardağan, Rethinking the Jewish Communal Apartment in the Ottoman Communal Building in “Middle Eastern Studies,” Vol. 42, No. 2 (2006).

David Bunis, Judezmo: The Jewish Language of the Ottoman Sephardim in “European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe,” Vol. 44, No. 1 (2011).

Dina Danon, The Jews of Ottoman Izmir: A Modern History (2020).

Aron Rodrigue, French Jews, Turkish Jews: The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Politics of Jewish Schooling in Turkey, 1860-1925 (1990).

Daniel J. Schroeter, “The Changing Relationship between the Jews of the Arab Middle East and the Ottoman State in the Nineteenth Century” in Avigdor Levy (ed.), Jews, Turks, Ottomans: A Shared History, Fifteenth Through Twentieth Century (2002).

Hi Makena,

FYI, Haribi, Haim Nahoum actually visited Seattle in June, 1921. I believe that he came to raise funds for the Alliance Israelite Universelle. There was lengthy article in La America of June 3, 1921 regarding his visit. Although the article itself did not mention it, Haribi Nahoum visited a home near the corner of 25th Avenue and East Fir Street. Although I can’t put my hands on it right now there was a picture taken of all the attendees, many of whom I remember.

I will have to mail you the pdf I have of the article from La America separately.