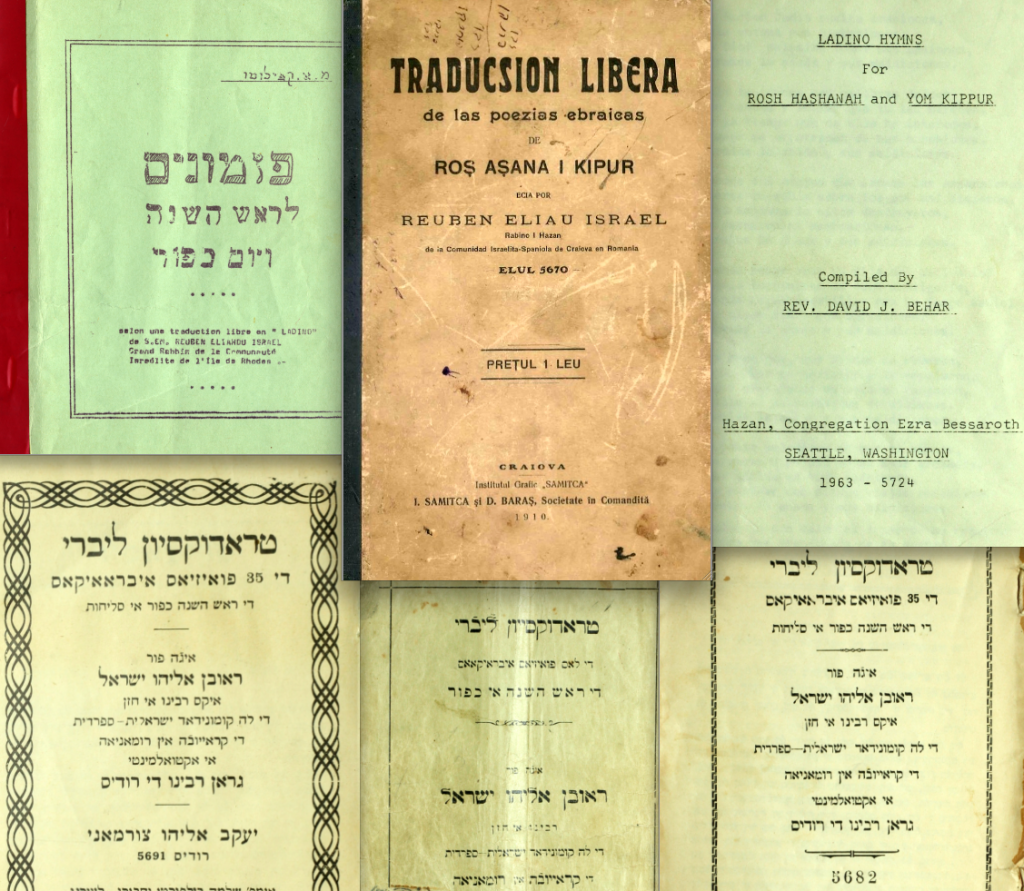

Rabbi Reuben Eliyahu Israel’s Traduksyon livre de las Poezias Ebraikas de Rosh Ashana i Kippur. Left to Right: Brussels, 1973; Craiova, 1910; Seattle, 1963; Rhodes-Livorno, 1931; Izmir, 1910; Izmir, 1922

The congregants complained to the rabbi that they didn’t understand the prayers in Hebrew. “They say with regret that the prayers of the High Holy Days do not make any impression upon us; to the contrary, these prayers are even terribly boring for us, and we have to spend so many hours in the synagogue singing and reading in a language that is totally unknown to us.” Hearing this, Rabbi Reuven Eliyahu Israel took it upon himself to translate the most important poems in the holiday liturgy into the spoken language of the Sephardic Jews, Judeo-Spanish, in order “to lift us out of our lethargy and awaken in us sentiments of piety and devotion.” In short, he sought to inspire in his congregants a deep understanding and a sense of spiritual connection during the High Holidays—a connection that echoes into the twenty-first century.

In 1910, Israel published two editions of Traduksyon livre de las Poezias Ebraikas de Rosh Ashana i Kippur (the introduction is quoted above): one in Latin characters to cater to his small, more assimilated and Europeanized congregation in Craiova, Romania; and one in Hebrew characters for his more traditional native community on the island of Rhodes, which was still part of the Ottoman Empire at the time. Since then, at least eleven versions of Israel’s Free Translation of Hebrew Poems for Rosh Ha-Shana and

While quite popular here in Seattle, very few exemplars have been preserved elsewhere in the world: Worldcat, the most comprehensive library catalog, indicates that only five copies of the first edition are available in libraries today. Our collection proudly adds another three first-edition copies to the list as well as a previously unstudied edition—that very first edition published in Romania that was thought to have been lost.

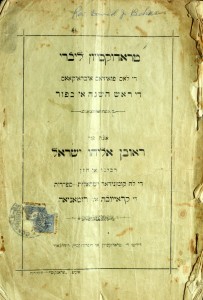

Rabbi Israel’s Traduksyon livre de las Poezias Ebraikas de Rosh Ashana i Kippur (Free Translation of Hebrew Poems for Rosh Ha-Shana, and [Yom] Kippur) published in Izmir, 1910. Note the signature of Rev. David J. Behar at the top, an indication that this text was once in his possession. (Courtesy of Larry Azose)

At the same time, Israel described his poems as preserving the tradition, as tradusidos tekstualmente del ebreo, “textually translated from the Hebrew.” He meant that his translation, even though more easily understood, nonetheless closely mirrors the original Hebrew in terms of content and meaning, and with a cadence and rhythm that would accommodate the traditional melodies used for the Hebrew liturgy. Although his translation was original, Israel stressed: “I went to great lengths to harmonize my words with the traditional tunes used among us.”

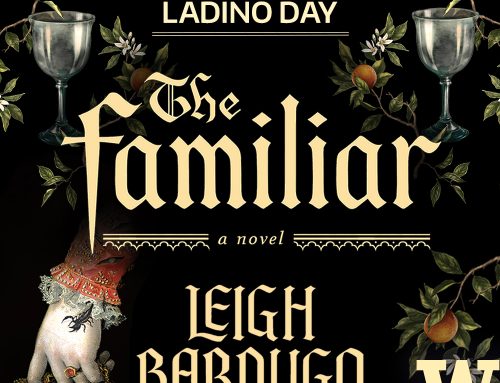

Israel’s strategy of seeking to reconcile tradition and modernity bore fruit. Jews in Rhodes incorporated the Craiova-inspired translation into their High Holiday services and brought it with them to the new communities they established in the twentieth century as part of a far-flung Rhodesli diaspora. Rhodeslis printed new editions of Israel’s translation in major hubs of Rhodesli settlement, including Buenos Aires, Brussels, Jerusalem, and Seattle. Just in Seattle, the book underwent four updates. Notably, none of these editions reproduced Israel’s original introduction that explains why he undertook the translations in the first place, but instead contain just the translations themselves.

Like the first edition in Craiova, the editions by Salvador Tarica in Buenos Aires (1937) and Reverend David J. Behar in Seattle (1963) were printed in Latin characters to make them easier to read by congregants less comfortable with Hebrew. In the United States, the new edition was of great significance because many Sephardic congregations, including those established by Rhodeslis, adopted a new High Holiday prayer book published in New York by Reverend David de Sola Pool, the spiritual leader of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue. He sought to standardize the American Sephardic liturgy and in the process excluded all passages in Ladino.

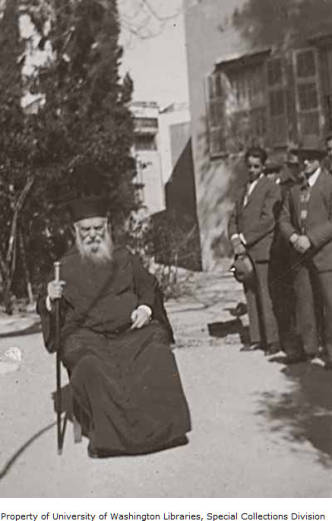

Rabbi Reuben Eliyahu Israel on the Island of Rhodes, May 1929. (Courtesy of the WSJHS collection at the University of Washington Digital Collections)

As a way to compensate for this loss, Reverend Behar’s transliteration and reprinting of Israel’s High Holiday translation was intended to supplement the de Sola Pool prayer book and revive the Rhodesli tradition. When Hazzan Isaac Azose, who succeeded Reverend Behar at Seattle’s Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, published his own High Holiday prayer books, with the goal of restoring the Rhodesli traditions that had been excluded from de Sola Pool’s prayer book, he unsurprisingly included many of his own adaptations of Israel’s Ladino translation of the High Holiday poems. They continue to be sung today at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth.

Until now, the original Romanian edition had not been studied—Jerusalmi did not consult it in his scholarship and only one copy was known to exist, housed at the National Library of Israel.

That changed recently when our Sephardic Studies Program received an email from a woman in Johannesburg who disclosed that she had a copy of the original Romanian version, with Romanian footnotes no less! Her grandmother, Olga Benatar, was born in Rhodes and had left the island with her family in 1910 to live in Heliopolis. In this ancient city, which Sepharadim identified as the biblical city of Raamses, now a suburb of Cairo, she married a Libyan Jew, Joseph ben Haim Naim of Tripoli, whose mother had emigrated from Livorno, Italy. In September 1928, together with her husband and two daughters, the family left Egypt and settled in Johannesburg where another center of Rhodesli settlement had been established. With them went the book.

![Rabbi Reuben Eliyahu Yisrael’s Traducsion Libera de las poezias ebrraicas Ros Asana I Kipur (Free Translation of Hebrew Poems for Rosh Ha-Shana, and [Yom] Kippur) published in Craiova, Romania, 1910.](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/1.-Craiova-1910-I.-Samitca-şi-D.-Baraş-ST001397-Traducsion-Libera-de-las-poezias-ebrraicas-Ros-Asana-I-Kipur--187x300.jpg)

Traducsion Libera de las poezias ebraicas Roş Aşana I Kipur (Free Translation of Hebrew Poems for Rosh Ha-Shana, and [Yom] Kippur) published in Craiova, Romania, 1910. (Courtesy of Linda Lurie)

The irony is that while Israel created his “free translation” so that the High Holiday poems could be understood by everyone in what was then their spoken language, Judeo-Spanish, now few remain who can understand that language. Instead, the poems continue to be chanted in Judeo-Spanish not because everyone can understand, but rather because that is now the established and honored century-old custom of the Rhodeslis. Hazzan Isaac Azose recorded several of these songs and has kindly provided his rendition of Little Sister, Ahot Ketana (La Nasyon Djudia) originally composed in Hebrew by the 13th century poet Abraham Hazan of Gernona, available here:

![Ahot ketana from Traducsion Libera de las poezias ebraicas Roş Aşana I Kipur (Free Translation of Hebrew Poems for Rosh Ha-Shana, and [Yom] Kippur) published in Craiova, Romania, 1910.](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Ahot-Katana-by-Abraham-Hazan-Girondi-13th-century-Spain-ST001397-Traducsion-Libera-de-las-poezias-ebrraicas-Ros-Asana-I-Kipur-9-663x1024.jpeg)

Ahot ketana from Traducsion Libera de las poezias ebraicas Roş Aşana I Kipur published in Craiova, Romania, 1910.

Anyada Buena, Dulse i Alegre! May you have a good, sweet and happy New Year!

We are extremely grateful to the following individuals, families, and synagogues for providing the Sephardic Studies Program at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies with over 20 copies of the multiple editions of Rabbi Israel’s liturgical poems.

Our sincere appreciation to: Linda Lurie, Larry Azose, Grace Azose, Al Maimon, Leatrice (nee DeLeon) Gutmann, Myrna Barkey Mitnick, Hazzan Isaac Azose, David Behar and his father Elazar Behar (z”l) from the Reverend David J. Behar collection, Naomi Strauss from her father Rabbi Dr. Isidore Kahan’s collection, David and Joy Maimon from the Prof. David Romey collection, and Richard Adatto from the Albert Adatto collection as well as Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation.

This was very informative. I did not know that this literature still existed. Thank you

Eleanore Reznik

I love listening to Sephardic liturgy, it just brings such great memories of my childhood at Teferith Israel in Los Angeles,going to temple with my Greek Romaniot grandmother.