Winner, student category – 2024 “Muestras Konsejas” essay competition. See all winning essays.

Family photo. First row from left to right: Nava, Avram Hatem, Emel, Roza Hatem. Second row from left to right: Doron, Eliza.

By Liza Cemel

Liza Cemel

26th October of 1962 Jak from Antakya and Eliza from Çanakkale, whom I am proud to call my namesake, united their lives. That story on its own is timeless and is not bound by space. It is also a story of the birth of a new and large family, two different lives, two different cultures, and two different families becoming one. It is a story of how the distance between two cities,

Antakya and Çanakkale, a distance which seems so great, can be bridged by love. Unexpected encounters can sometimes be the greatest sources of peace.

It was also the time Eliza moved from her home, from her family and from her one and only sister, Nava, at the age of 16. Bittersweet. Ladino followed her in her validja. She never forgot the cultural richness she brought with her from Çanakkale.

1963, they reunited in Çanakkale, this time with Jak and Eliza’s little baby, Emel.

It was not so long after that they reunited and found their way back to each other, but only to say goodbye…

Another year, another separation. June 1965 was a turning point in Nava’s life. Nava and her parents set off from Çanakkale to Istanbul and then for the destination of Israel. As there were no direct ships, the ship made a short stop in İskenderun, where Nava and her parents Roza and Avram Hatem could meet Eliza, Jak and little Emel. They approached the ship with a little boat to meet with Nava and the parents. The distance became as close as 200 meters, only to make it 862.4 km…

It was an encounter of about half an hour. After 59 years, Nava still recalls how exciting it was to meet them. Their mom Roza gave Emel a white dress as a present. Perhaps Emel was too young to remember this, but it meant a lot for Nava’s memory of that moment.

From Çanakkale to Antakya… From Çanakkale to Israel…

Shores of the Mamara Sea in the port of Çanakkale

To reunite in Iskenderun. City of the port. City of so many reunions and separations.

I have always seen İskenderun as Antakya’s sister city. Sometimes in rivalry, mostly hand in hand. Me and my family were in Antakya, beside the summers in İskenderun and in Arsuz. The two districts are within the province/city of Hatay and the ancient settlements of Antioch (Antakya) and Alexandretta (İskenderun) constitute the two largest populations. İskenderun has one of the largest ports of Turkey and thus has an important position in maritime trade. Nava’s İskenderun and Antakya connection started with Eliza’s and Jak’s love story. Antakya was a paradigm for coexistence. A place that always has been shown as a model. Such an ancient settlement was honored with such a diversity. Çanakkale likewise: “We have nostalgia for a peaceful life, for the house, the synagogue, the holidays, the Hamam, the promenade on the beach and the picnics we used to have in the area of ancient Troy which is close to Çanakkale and also in places like island Bozcaada, Gelibolu…” says Nava.

Çanakkale promenade

Neighborliness is special in both cities. Good neighbors are like gems, always preserve their value and come wherever you go, of course in your validja.

Although Nava also recalls that the atmosphere towards Jews was at times negative. She adds: “No wonder why many moved in the 60s. As everywhere, some didn’t like the Jews. I recall a case that some family’s children, presumably, that lived near our street threw stones at some Jewish house.” I think it was the pattern to swallow all unpleasant and hostile situations, keep the “Kayades3” and just to look forward.

Year 1966. June. Towards the end of the springtime, the upcoming summer was about to bring good news, new beginnings, and endings.

My grandmother was pregnant with my mother. In fact, the young couple was excitedly counting the days, and my mom was almost ready to bloom like a flower from her mother’s womb.

Port cities have seen a lot: goodbyes, reunions, hugs, heartbreaks, regrets, fear, stress, grief, lamentation, excitement… maybe even have seen too much sometimes.

İskenderun was one of them. The historically rich city is also known as Alexandretta and Scanderoon, but in my world, it has almost been İskenderun.

İskenderun also has witnessed “Muestras Konsejas.” At a crossroads of life and stories, it has heard a variety of languages since its existence. Ancient Greek, Aramaic, Persian, Latin, Classical Arabic, Judeo-Arabic, Hebrew, Ladino, Assyrian, Armenian, French, and Turkish… are only some of them. The intersection of cultures, beliefs, civilizations, families, foods, languages, and arts is impressive.

Immigration. For some, it is a tough decision, and for others, it is a quick one.

Quick, as much as a sudden, “Aprontaremos las validjas.” Throughout Jewish history, we were forced to leave what we used to call “homes” wholeheartedly. Negative sentiments, hatred, expulsion, disentanglement, persecution, forced labor, torture, rape, and murder against Jews were never enough to destroy Jewish people, Jewish history, and Jewish culture. Las validjas were always ready to fit the dearest memories, most fragile emotions, the smell of the most loved ones, favorite books, and the photos that feel closest to reality. Because that was the only way to be reborn from the ashes and never to stop recreating. Destruction and creation go hand in hand, and endings are good friends of beginnings. Some new beginnings were more willingly done, yet still leaving homes was due to distress, and loved ones and memories behind resulted in distress.

Inside the Çanakkale synagogue

I am someone nostalgic, even sometimes living in the past. Always wished to have a time machine. I needed to see how life was back then. I was just so curious about how our lives today were shaped by our past; how we think, feel and act. A time machine would have given me enough information to “grasp” my family’s history, which otherwise is difficult to acquire…

Time is value, time is stories, time is suitcases. In the end, life is what you choose to take it with you, when no time and space is left. Symbol of las validjas is all about our squeezed yet so precious stories.

I am inspired by las validjas and for that introduced lexicon, I should thank my thesis process and Rıfat N. Bali, an independent scholar on Turkish Jewry. While I was doing readings, I came across to this title “Aprontaremos Las Validjas” (Shall We Start Packing the Suitcases?) in the epilogue of the book “Turkish Jews and their Diasporas: Entanglements and Separations.” At that moment, I was impressed by the term and thought it resonates with my family story, and probably with many others too. So the rhetorical question is: “Aprontaremos las validjas? Shall we start packing the suitcases?” Further questions arise from such a question. Did Jews mentally leave Turkish cities? Are they always prepared to leave with suitcases in case something unfortunate happens? Always-on-the-way Jews were always ready to leave, and to bring their culture and memories with them. It is no different for the case of Çanakkale and Antakya Jewry.

Indeed most of Turkey’s Jews packed their suitcases and left long ago.4 My reference is mostly relating to a traveling identity, an identity which is brought by the members and is shaped with their new established places.

By June 1966, my grandma and her sister were already separated by distance. My grandma was already living in the vicinity of İskenderun, in another culturally rich city, Antakya, historically known as Antioch. She herself, at a young age, moved to the other side of the country to unite lives with my beloved grandpa, who then she knew little. On the other side of the coin, their meeting also marked the birth of the multicultural, new, large family of two different cultures: families and lives, which became one.

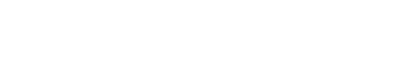

Roza and Avram Hatem (parents of Eliza & Nava) with Nava visiting Antakya, Turkey. Pesach, 1965.

Considering today’s conditions, it may seem like a simple plane ride, but in the ’60s, from Çanakkale to Antakya was a considerable distance. Today, the car ride is approximately 15 hours and 1,275.2 km (792.4 miles). My grandpa’s father was a manufacturer in the Antakya Bazaar, and his mother was a housewife. He was the middle child of six siblings, and his childhood was spent in a crowded family environment, playing şeş beş. When he came of military age, he was assigned to fulfill his military duty at a primary school in Çanakkale, as per the conditions of the time. He could not have predicted that his life would change so dramatically in Çanakkale, where he would stay for only two years. Madam Bibinuta, the boarding house owner where he stayed as a boarder, took a liking to Antakya-native Jak and embraced him like a son. She loved him so much that Jak became like part of the family, no longer just a temporary guest. She introduced him to Eliza, the beautiful daughter of a family from Çanakkale, whom she knew well. It was such a fitting match that their respectful and loving relationship lasted for 58 years, constantly growing more robust. They became a couple that those around them looked up to and emulated. Despite their differences, they found common ground in the shared Jewish heritage that had been passed down through generations.

If Çanakkale was the turning point for Jak from Antakya, then Antakya was the turning point for Eliza, from Çanakkale. Eliza, who speaks Turkish and Ladino, completely changed her life and became a bride in Antakya. She began speaking Judeo-Arabic like a native, even though she had never known the language before. She was an expert in the local Antakya cuisine. (She still is today!) Even though she left home at the age of 16, she still speaks Ladino with her family, never forgetting her Çanakkale and her cultural richness. She cooks both Antiochian and Halabi food, as well as Sephardic food.

Eliza (left) and Nava (right), sisters, in front of the entrance of the Mekor Hayim Synagogue in Çanakkale, October 2015. The synagogue was built about 200 years ago and its restoration began in 2000

Her sister was 10 years old when she, her parents, and her brother were on a boat to Eretz Israel. Despite the long-told tale of the peaceful and “tolerant” lands and rulings in today’s Middle East and North Africa, it was always relative. A combination of negative attitudes towards the Jews in Çanakkale in modern-day Turkey and the spark of Zionism paved the way for such a movement. Two sisters lived two completely different lives. Whether “geography determines fate” still remains an open question among people; it indeed plays a crucial factor. Two distinct realities shaped my grandma’s and great-aunt’s lives. Ladino connected them both. Whenever I see them together in person or now on a video call, there is an incredibly inseparable connection between them. Through a unique language, their souls, past and current lives, knitted together.

Since Nava came to Israel, they ceased speaking Turkish, they only spoke Ladino at home, something that made her forget Turkish to a great extent and at the same time made her stay connected to Eliza through their mother-tongue Ladino. “We often reminisce about our lives in Çanakkale and even visited there together several times as part of the visits organized by Selim and Aron5.”

Nevertheless, one continued her life as a housewife in a rather rural area of Turkey, at the southernmost point, flourishing with the area’s welcoming people, delicious Jewish Halabi recipes, mastering Judeo-Arabic, contributing to the crowded family, and raising children. On the other hand, my great-aunt worked her whole life at a big technology company, and she even recently completed her master’s degree in Ladino Studies. She is considering furthering her research and at the moment she writes articles on platforms such as Aki Yerushalayim. She immigrated at a young age and never got the chance to raise her children in a crowded family environment. She plays a significant role in Israel’s local, regional, and national Ladino and Sephardic Cultural Circle.

Neither of them is better than the other; they feed each other and grow together. It is a living example of a human mechanism and a support system.

“The boat” that was deemed to take my grandma’s family took off long ago, and she was there to watch the ship sailing away despite the furious speed of the waves, probably thinking, “No ay kualo azer.” herself. I knew her well and had the honor of being named after her. But she always managed to stay pragmatic while being very vulnerable and emotional.

In the order from left to right: Eliza, Bertha (Eliza and Nava’s cousin), Nava, Roza (Eliza’s daughter/my mom), Güneş (Eliza’s childhood friend from Çanakkale), Jak (Eliza’s life partner), from organized heritage visits to Çanakkale, in 2015.

This was one of many stories. Other family members also moved to the Americas. My grandma’s aunt immigrated to the U.S.A. Another sister of hers immigrated to the USA at an older age as well; her son, who used to live in İstanbul, ended up there, too. This did not happen in a vacuum. Tachlis, we don’t always have control over the threads of our lives and sometimes we can’t even predict where our decisions and plans will lead us.

“The spoken word flies away; the written word remains.” I believe that preserving history is of vital importance, especially in such disappearing Jewish communities where the number of Jewish community members has dwindled to fewer than ten fingers. The intimidating truth is that some of our most valuable family stories stayed unrecorded, becoming as sensitive as a thin thread, as fragile as an old family porcelain, and as vulnerable as a heart… No one is left to tell stories of the past that were passed down by word of mouth. I aspire and dedicate myself to doing so.

As vulnerable as it is, I feel an urge and a responsibility to engrave these stories in history. It is a contrast but not a dilemma for me. I know I am the one that will be taking over this mission. It is not a difficult decision nor a burden, it is almost a must, but a desired one. My ancestors may have not noted these down, maybe not even tried, nor even have thought of it. I used to hold them accountable, but I am aware that that does not help anyone. I, myself, have a chance to change something in the course of my time machine. I might have a positive influence for the forthcoming generations, to know more about “our validjas.” It seems to be a waste of time to complain in the remaining time. Our culture teaches us curiosity with questions and ideas with action. I want to be true to myself, to my family, to my culture and to my validja… With this validja, I am carrying memories and passing them on. If we need to re-pack las validjas, we will. Because that’s what we have always done. But “presiozas” will be with us forever…

Dedicating this piece to my presiozas; to two unique sisters who re-found each other and never left their validjas…

Kon paz i amor… Barış ve sevgiyle…

…בשלום ובאהבה

1 Expression for suitcase in Ladino/Judeo-Spanish.

2 Distance between Antakya and Israel (536 miles). Even though the distance between Çanakkale and Israel is 2.096,7 km (1.303 miles), the distance between Antakya and Israel is taken as a consideration, since that’s where Eliza and Nava, respectively, lived after separating.

3 “Silence” in Ladino. Also used as an expression in the Jewish community in Turkey to indicate community policy.

4 “Even after a century of republican government, the promise of a polity based on equal citizenship for all its citizens has failed to materialize.”(Öktem, Kerem, and Ipek Kocaömer Yosmaoğlu, editors. Turkish Jews and Their Diasporas: Entanglements and Separations. Springer International Publishing, 2022. p. 24)

5 Organized trips for elderly Jews originally from Çanakkale.

Presented in partnership with the Sephardic Brotherhood of America, the 2023-2024 “Muestras Konsejas” writing contest opened a new space for the telling of Sephardic stories. Writers were asked to share an original work of prose (fictional or memoiristic) that gives voice to the experiences of the Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jewish communities (whether from family lore, lived experience, community heritage, life stories, etc.). Stories from all over the world were read by an expert panel of judges, who selected four finalists (across both “General” and “Student” submission categories) as the inaugural winners.

This essay made my day. I’ve been researching my family history in Çanakkale during the past year and was delighted to read about another family’s diaspora from the Dardanelles, and especially to see the photos of the bus pilgrimage to Çanakkale with Selim. Thank you Liza! I hope to attend the bus trip in 2025.