By Devin E. Naar

A Jewish friend from Greece just sent me a holiday message: “Hag Sameah, although we Greeks don’t really like Hanukkah!” Indeed, it is only for Jews in Greece that Hanukkah seems to pose an existential problem, as it is typically considered a holiday commemorating the Jewish victory over the Greeks and their policies of forced Hellenization and religious persecution. It’s a holiday that splits the identity of the Greek Jew into two seemingly contradictory, mutually hostile parts.

Marcel Nadjary, pictured at the outset of the war several years prior to his deportation to Auschwitz. Source: The Jewish Museum of Greece

I received that message from my friend as I was reading about a new discovery in Auschwitz announced recently by the BBC and several other news outlets: A long-lost letter penned and buried in 1944 by a prisoner in Auschwitz was just decoded for the first time. Media coverage has focused on the devastating details revealed about the experience in the Sonderkommando, the brigade of Jewish prisoners charged with the gruesome task of transporting corpses from the gas chambers to the crematoria at Auschwitz.

But the fact that the letter was written in Greek by Marcel Nadjary, a Jew from Salonica (Thessaloniki) who had served in the Greek army, has gone without comment. Not only that, the letter is infused with enthusiastic expressions of Greek patriotism, concluding with the dramatic line: “I’m dying happy, because I know that at this moment our Greece is free. My last words will be: Long live Greece.”

If the Greek-Jewish relationship is somewhat fraught, as my Jewish friend in Greece recalls every Hanukkah, how could a Greek Jew from Salonica so unproblematically embrace his Greek identity in such horrific circumstances more than seventy years ago? A rare book published in Salonica during the war, in 1941, and preserved here in Seattle as part of the UW Sephardic Studies Collection, offers new insight into this pressing question.

Let’s remember that the story of Hanukkah also involved a kind of civil war that pitted the pro-Greek Jewish aristocracy against Judah Maccabee and his traditionalist opposition. The tale of the Maccabees is preserved in Greek (not Hebrew), and many Greek terms entered the Jewish lexicon, such as synagogue and bima (“tribune” or “platform”). Nevertheless, the Hebrew term, lehityaven, literally meaning “to become Greek,” is used to mean “to assimilate” (Yavan is the biblical place name for Greece).

Title page of Siddur Sha’are Tefilah. (From the collection of Albert Adatto, ST00348)

Although achieving independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, the modern state of Greece only gained a substantial Jewish population only in 1912/13. As I describe in my book, Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece, Greece captured one of the most significant port cities in the eastern Mediterranean during the Balkan Wars: Salonica. Designated the “Jerusalem of the Balkans,” Salonica was home to a robust population of predominantly Ladino (Judeo-Spanish)-speaking Sephardic Jews, descendants of those expelled from Spain and Portugal after 1492 whose rabbis transformed the city into a famed center of Jewish scholarship.

Until the twentieth century, Jews constituted the plurality—if not majority—of the residents of this multicultural city. Never restricted to ghettos, Jews could be found in every social strata: from merchants and teachers to tobacco laborers and stevedores, gangsters and prostitutes. Jewish workers organized the largest Socialist movement in the region. The Jewish imprint on the city was so profound that commerce ceased every Saturday in observance of the Sabbath. Zionist leaders like David Ben-Gurion saw in Salonica a model for a self-governing Jewish society that he hoped would arise in Palestine. In fact, as an alternative to the incorporation of the city into Greece in 1912, local leaders proposed that Salonica be transformed into an international city with a Jewish administration—a kind of Jewish city-state. It was not to be.

Could the divide between Greeks and Jews be bridged in the new context of the Greek state? For modern Greeks, Orthodox Christianity had formed the core of national identity: the war of independence was launched in the name of “faith and fatherland;” the country’s constitution—still today—is articulated in the name of the holy trinity; and, like other European countries, the national flag incorporates the cross. Could Ottoman-born Ladino-speaking Jews become “Greek”? Would learning Greek—the “beautiful language of Homer”–and a willingness to defend their new homeland be enough? Could one become Greek without being Orthodox Christian, or without Greek “blood” coursing through one’s veins?

Like elsewhere in Europe, the Greek state imposed new measures to try to “nationalize” its minority populations, including Jews. Jews themselves were divided over how to respond, as evidenced by the many Jewish political parties that emerged, including secular and religious Zionists, diaspora nationalists and localists, socialists and communists, and even Jewish fascists. They disagreed vehemently, sometimes violently, yet all continued to participate in the governance of Jewish communal institutions—schools, neighborhoods, orphanages, a hospital, insane asylum, and many other philanthropies. All parties engaged with the ideas of nationalism and sought to reimagine themselves as “Hellenic Jews” or as “Jewish Hellenes.” The vast majority held Greek citizenship, yes, but could they be accepted as part of the Greek nation?

Tensions mounted in the 1920s and 1930s even as more Jews—especially the youth born after 1912—began to see themselves as part of Greece; they learned Greek at school and the young men served in the military. But with the influx of a hundred thousand Orthodox Christian refugees into Salonica in the 1920s, following a war between Greece and Turkey, Jews no longer constituted the plurality of Salonica’s inhabitants. Seeking to gain an upper hand in the city’s commerce, refugees lobbied the government to implement a Sunday closing law—to disadvantage Jews in commerce or compel them to be less observant. During the depression, they launched the city’s first pogrom, in 1931.

Tensions between the two populations mounted, not necessarily because the Jews weren’t becoming “Greek”, as is often claimed, but rather because they were becoming Greek while remaining Jews. They were changing the meaning of what it meant to be Greek: not Orthodox Christian, not of Greek “blood,” but rather residents of Greece, holding Greek citizenship, speaking Greek (not to the exclusion of other languages), and expressing a sense of patriotism.

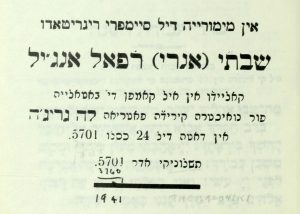

Dedication in Sha’are Tefilah in memory of Shabetai (Henri) Rafael Angel, a Jewish soldier who died in battle fighting for “our beloved homeland, Greece” (kayido en el kampo de bataya por nuestra kerida patria, la Grecha)

As the Second World War began, the dynamics at play in Greece were unlike those elsewhere in Europe. As Jews were being expelled from universities and the professions across the continent, in Greece, Jews were being integrated into public schools in unprecedented numbers. The Greek state—which never implemented separation of Church and state—even collaborated with the Jewish community to compose new textbooks, in Greek, about Judaism to be used in public schools! A Jewish intellectual, Michael Molho, argued in 1939 that while Jews persecuted across the continent were crying out from the “valley of tears,” cheers of “hallelujah” were shouted loudly from Greece.

Continuing to plan for a Jewish future in Greece, even once the country entered the war against Italy in 1940, Jewish leaders in Salonica published a new prayer book, Sha’are Tefilah, in March 1941. One of the pioneers in the field of the Sephardic Studies in the United States, the Istanbul-born and Seattle-based writer Albert Adatto acquired an exemplar of this rare book, thereby enabling us to access the long-lost world of Jewish Greece on the brink of destruction.

Remarkably, the editors of the prayer book—Salonican-born Jews who had been educated in Palestine—dedicated it to a Jewish soldier who had fallen on the battlefield defending “our beloved homeland, Greece.” Written not in Greek, but rather in Judeo-Spanish, the dedication aimed to show to Jews themselves that they ought to think of themselves not only as religiously Jewish and culturally Sephardi, but as Greek patriots, too. They believed that all of these allegiances could be held simultaneously.

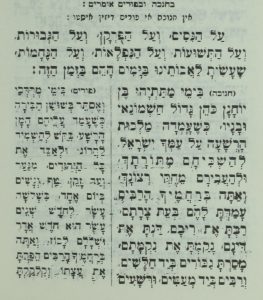

The Al ha-nissim prayer from Siddur Sha’are Tefilah. It omits the standard reference to the “wicked Hellenic government.” (ST00348)

But in order to accommodate their Jewish and Greek identities, they made two noteworthy changes to the prayer book. In the Al ha-Nissim prayer added to the Hanukkah liturgy that refers to the miracles associated with the holiday, the traditional reference to the “wicked Hellenic government” is quietly changed to the “wicked government.”

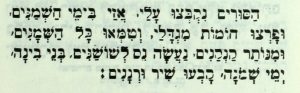

More remarkably, in Maoz tzur (“Rock of Ages”), the popular Hanukkah song, the reference to the enemy as Yevanim (“Greeks”) is replaced by Suriim (“Syrians”). The editors accomplished this clever switch by reference to the historical record. The Seleucids, the Hellenistic empire in control of Judea at the time of the Maccabees, were indeed culturally Greek, but they were geographically based in Syria. Hence the Salonican Jewish leaders could transform the “Syrians” into the Hanukah enemies and thereby more easily embrace Greece as their beloved homeland.

Despite this sense of Greek patriotism cultivated by Salonican Jewish leaders, when the deportations to Auschwitz began in March 1943, local Greek state representatives and Orthodox Christian neighbors neither intervened nor objected. In contrast, the local population participated in the dispossession of the city’s Jews, taking over thousands of homes and businesses. The university and the municipality—not the Nazis—initiated the destruction of the Jewish cemetery that stretched over a terrain the size of eighty football fields and housed more than 300,000 graves. Even though Jewish leaders argued that the cemetery ought to be preserved as a monument of Hellenic patrimony that documented not only the Jewish past, but also the history of the city and the country as a whole, the call fell on deaf ears.

Text of Hanukkah song, Maoz tzur (“Rock of Ages”), from Sha’are Tefilah. This version refers to the “Syrians” rather than the “Greeks” as the adversaries.

At Auschwitz, Jews from Salonica developed a distinctive reputation, as characterized by Primo Levi:

Next to us there is a group of Greeks, those admirable and terrible Jews of Salonika, tenacious, thieving, wise, ferocious and united, so determined to live, such pitiless opponents in the struggle for life; those Greeks who have conquered in the kitchens and in the yards, and whom even the Germans respect and the Poles fear. They are in their third year of camp, and nobody knows better than they what the camp means. They now stand closely in a circle, shoulder to shoulder, and sing one of their interminable chants

Although shaped by Orientalist imagery, Levi’s account notably refers to Salonica’s Jews unquestionably as “Greeks.” One wonders in which language those “interminable chants” were sung? Greek or Judeo-Spanish—or both?

The experience in the Sonderkommando offers a clue. The Nazis compelled a disproportionate number of Salonican Jewish men to participate in the Sonderkommando, in part due to a perception of their exceptional physically fitness, but also because they were isolated. Without knowledge of German, Polish, or Yiddish, Jews from Greece could not easily communicate with other prisoners, let alone the immediate outside world.

Despite their sense of isolation, a number of Jews from Greece nonetheless succeeded in establishing contact with the Polish underground and initiating the only major uprising in Auschwitz, in October 1944. They succeeded in blowing up one of the crematoria. Tales circulated that in the wake of the uprising, Salonican and other Greek Jews in the Sonderkommando dramatically chanted the Greek national anthem prior to being executed for their role in the revolt.

Of course, one must ask: why the Greek national anthem? It is a challenging question to answer.

Marcel Nadjary’s recently decoded letter offers another clue. He requests that his letter, if unearthed, be delivered to the nearest Greek consulate. He then dedicates his missive “to my beloved fatherland, GREECE, to whom I was always a good citizen.” While much of the text does focus on the devastation and unspeakable hardship confronted by the Sonderkommando, it is also overflowing with expressions of patriotism: “At least we Greeks are determined to die like true Greeks, just like every Greek knows how to leave life, by showing until the very last moment, despite the dominance of the criminals, that Greek blood is flowing through our veins.” It is remarkable that he refers to “Greek blood” flowing through his veins, for it was precisely the sense that Jewish “blood” and Greek “blood” were fundamentally different that led to his deportation.

Detail showing how Marcel Nadjary’s letter was reconstructed. On the right is the original page. On the left is a version made legible through digital image correction. Pavel Polian:Institut für Zeitgeschichte (via The Forward)

The letter continues with similarly patriotic statements: “Fate doesn’t want me to see our Greece as a free man… Whenever someone asks after me, simply say that I no longer exist, and that I have gone as a true Greek.” And the letter concludes with Nadjary’s emotional declaration of his last words: “Long live Greece!”

Perhaps Nadjary’s words, plus those of the Sha’are Tefilah prayer book, should no longer make it so challenging for the few thousand Jews remaining in Greece today to celebrate Hanukkah. As these sources reveal, Salonican Jews sought to show that they felt like Greeks even as they remained Jews. It is now up to the Greek state, and the majority of Greek citizens, to embrace Jews and others as equal members of society.

The future of the nation-state remains uncertain across the globe. But if and while it remains the main form of geopolitical organization, we ought to consider the argument made by Greek Jews: that membership in the nation–in any nation–should not be contingent upon one’s blood or religion, but rather one’s engagement with the national culture and embrace of the homeland—combined with the right to be different. That’s an additional Hanukkah message that should resonate today.

Interestingly enough, the negative comments about Maoz Tsur made by Amos Oz’s heroine Sonia in “A Tale of Love and Darkness” have been included in Jakov Simpi’s Greek translation but they have been omitted from Nicholas de Lange’s English translation! Basically, Sonia thinks of those lyrics as being “very very bad if not Nazi”, right after the fabulous boat-to-Palestine scene of encountering a Greek lady and her baby, whom she momentarily thinks of being closer to her than the Jewish people, “despite the wicked Jew-hating Antiochus

Epiphanes” — a rather magnificent moment of the novel (section 27 (26 in English translation)) … that Oz masterfully employs to cast fleeting doubts about Zionism and Israel (for one and only one time in the novel, Ibelieve).

I do believe the commentary was very historically accurate and I applaud the scholar for bringing it out I must mention though that The Ottomans unfairly get credit when in reality all the worse he was monetary gain through there laws that applied to both Christians and Jews through heavy taxes another thing is Romaniote we’re almost wiped out when the Ottomans in there earlier processors the subjects arrived in Asia minor they did not do you differentiate between RUM what they called the Greeks since technically speaking the Roman empire shifted to the east and for time the capital was in Constantinople in 330A.D. Joseph Hacker writes extensively about the fate of the Greek Jewish population prior to the Spanish and Portuguese coming. https://www.americanthinker.com/articles/2005/10/ottoman_dhimmitude.html

excuse the typos I must say it’s early

Well written it brings to surface questions that I had until I met some of those Sephardic Jews of Salonica. Hannukah is controversial to the Sephardic Jews since it happened prior to their arrival to the Balkans, as such they weren’t part of it. The Romaniote Jews who existed in today’s Greece since before Jesus walked this earth are a different story on the other hand. One thing that I find of interest here is whether there are ethnography studies that discuss the length of time that it takes for new transplants to feel citizens of their host country and whether it depends on the circumstances that people leave their home country and where they go. Also, does it change with time. So here in America how long does it take to feel American? Do the first generation immigrants ever truly feel American or is it their offspring that does? Look at Yiannis Antetokoumpo. He proclaims to be Greek everywhere he goes, did his parents feel Greek? Does he feel American now that he’s been here a while? Will his kids ever feel Greek or Nigerian? In the case of the Sephardic Jews it would be interesting to know their role during the Greek revolution. At that time they had been in Greece for almost 300 years. Once again excellent work Devin!

Extremely interesting work, Professor

99.9% of Greeks do not know what is Hannukah! I found out when I went to Israel! Greeks do not hate Jews and also Greeks never actively participated at the deportation. At that time it was not known even amongst Jews that deportation meant killing in Auswitch! In fact some Jews in Verroia say they did not know if it was better to be deported or fight in the mountains with Greeks against Germans! In fact many Greeks safeguarded the fortune of Jewish people. In fact Greeks lost 10% of all the population fighting the Nazis. To me this article is an unfair propaganda against the Greeks!

I´m Greek myself and I’m really fascinated with the history of the Jewish diaspora, my forefathers surname was Adamis a surname that has been classified as one of those surnames that Jewish people used to have in Greece. Like the lady before me, I can assure you that the percentage of Greeks who have no idea what Hanukkah is all about is a little more than 99.9% and please renew your views towards how Greeks feel about Jews, I live in Greece and I can tell you by first hand that Israel is viewed quite positive, Greeks love to learn about Israel and at the end is quite difficult to find a country as friendly to Israel as Greece in all of Europe nowadays. Blessings to all of you!

Ironic tonight is Hanukkah and my 2nd year without family, so to speak — lineage German Jew American, how I came across this article — I was reading up as tonight Hanukkah. Greeks have no idea about Hanukkah, ironic — hard to believe — the 8 nights “the oil lasted” — but then again perhaps something if you’re not Jewish you wouldn’t know … but then again you’d have to have your head in a “cloud” because during this month of December “Christmas/Hanukkah” are the 2 holidays people are rushing around and about! Time has passed, I hold nothing against the Greeks, do I remember the Greeks with Hanukkah, yup! Now I’m German – did I resent them yes, did I get past what happened — can I forget … depends. Problem here in the U.S.A. we hope no anger, resentments towards Jewish people; maybe we just need to move forward … not easy, we all have our memories … history does happen, give it to god he remembers – he forgives.

I happen to know what Hanukkah is but only because I’m a history geek who reads a lot. Most of my fellow Greeks however have probably at best only heard it as word, a Jewish festival celebrated around Christmas time, but have no idea what it’s about, or have any idea who Antiochos Epiphanes was…even though theoretically they should know, considering 1 & 2 Maccabees are included in the “deuterocanonical” texts of the Septuagint (Greek Old Testament) which the Greek Orthodox Church officially uses.