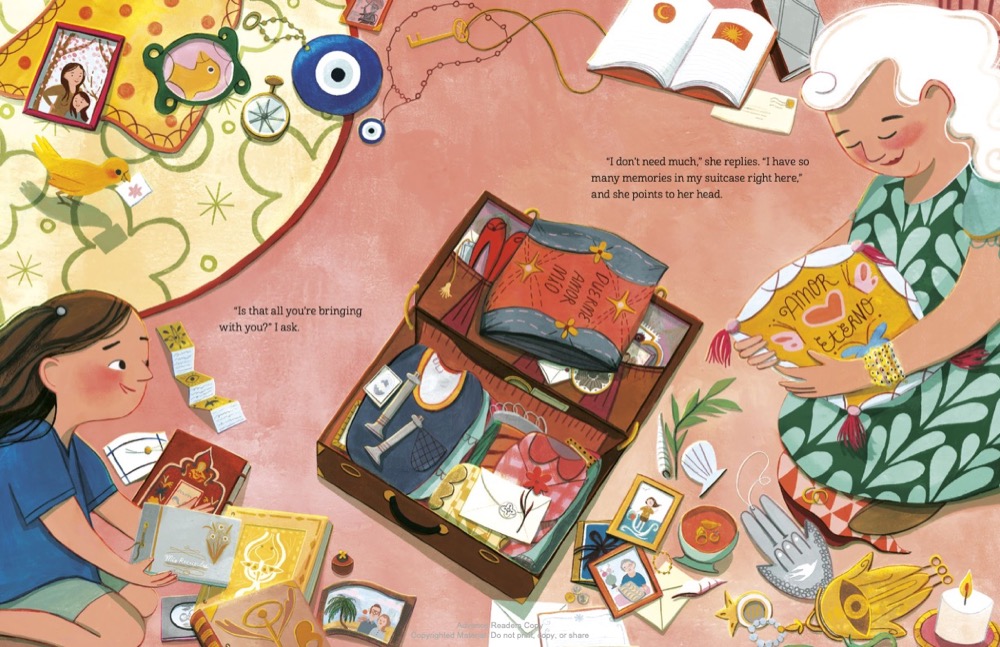

Spread from “Tía Fortuna’s New Home” by Ruth Behar. Illustration by Devon Holzwarth (Random House Kids, 2022).

By Hannah S. Pressman

“Today is Tía’s last day at the Seaway.”

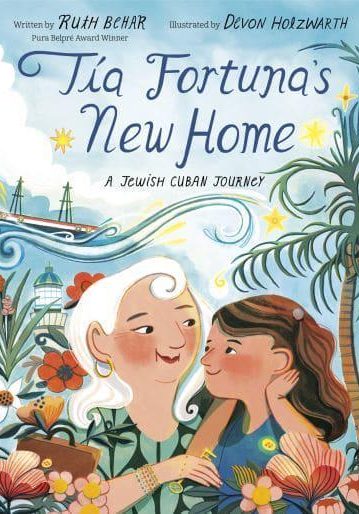

This statement appears early on in “Tía Fortuna’s New Home“, the new children’s book from renowned Cuban-Jewish anthropologist Ruth Behar. Through the voice of Tía Fortuna’s young niece Estrella, Behar has created a poignant tribute to Sephardic families past and present. Anyone familiar with Sephardic history will recognize, in Tía Fortuna’s departure from her beloved casita (bungalow) in Miami, echoes of other departures in Jewish history, some voluntary and some decidedly not.

The long-ago expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula and horrifying events of the Spanish Inquisition loom large in Sephardic collective memory. Leaving a place behind while carrying its essence with you — in the form of recipes, ritual objects, a mother tongue, or even transmitting legends about safeguarding a key to one’s former home — is a recurring theme in Jewish historical narratives.

Yet what Behar achieves in “Tía Fortuna’s New Home,” whose target audience is children ages four to eight, is to take those violent historical disruptions and to evoke them emotionally, rather than literally, through a tender story about an intergenerational relationship. As a result, her book effectively communicates to young children that Jews have had to leave many places, many times; however, as Fortuna tells Estrella, “We come from people who found hope wherever they went.”

From anthropology to children’s literature

Award-winning author Ruth Behar, a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan. (Photo by Gabriel Frye-Behar)

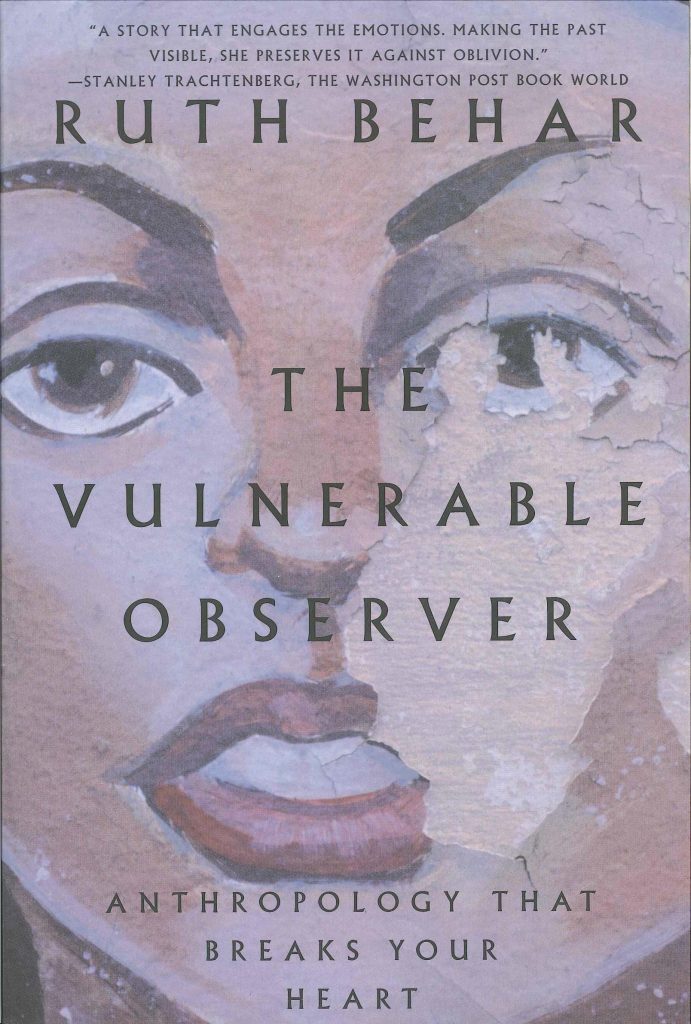

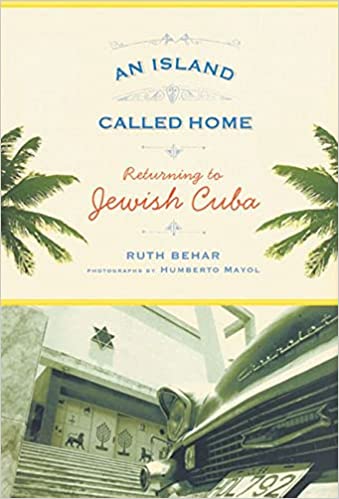

Across a multi-genre writing career including academia, memoir, and poetry, Ruth Behar has emphasized the importance of traveling and coming home. With influential works such as “The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart” (1996) and her pioneering study of Cuban Jews, “An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba” (2007), she has mapped a field of ethnography that emphasizes border-crossing and self-investigation. Behar has been recognized with a MacArthur “Genius” Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and, this past year, election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The self-described “diasporic anthropologist” is currently the Victor Haim Perera Collegiate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan.

Pivoting to children’s literature has enabled Behar to explore some of the same themes as her anthropological scholarship through a new lens: she now filters the seismic shifts of Jewish history, as well as the internal earthquakes of coming-of-age, through the eyes of young characters for the benefit of young readers. She is relishing this new branch of her writing: “It’s so great to be able to communicate with a child. We were all children once; it’s this country that we all lived in once, but then we move on to live elsewhere. To be able to communicate with a young person is such an incredible experience.”

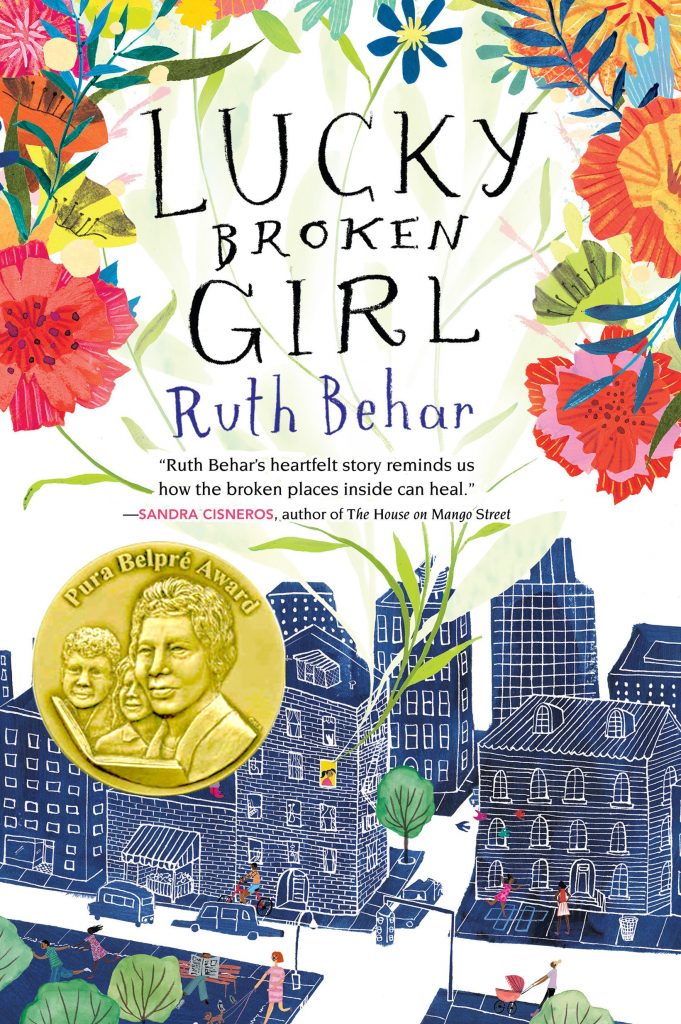

Behar began her career as a children’s author in 2017 with “Lucky Broken Girl,” a middle-grade novel based on her own experience as a Cuban immigrant in New York City. Ruthie, the “broken girl” of the title, is confined to her bed for months after a car accident, just as Behar herself was in the 1960s. “Lucky Broken Girl” won critical acclaim and many accolades, including the 2018 Pura Belpré Author Award from the American Library Association, which recognizes a Latino or Latina author and illustration for an outstanding portrayal of the Latino cultural experience.

Covers of Behar’s published works, from 1996 through 2020.

Behar followed that up with “Letters from Cuba“ (2020), an epistolary novel tracing the attempts of a Polish-Jewish family to escape Europe and start new lives in Cuba at the onset of World War II. The main character, a determined young seamstress named Esther, was inspired by Behar’s maternal grandmother of the same name. (See this 2015 profile for more about Behar’s Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish roots.) “Letters from Cuba,” which now also appears in a Spanish edition, was named a Sydney Taylor Notable Book by the Association of Jewish Libraries in 2021.

Buoyed by these initial successes, Behar nevertheless found writing for the pre-K set to be, in some ways, a tougher assignment than writing for tweens. Since far fewer words are allotted for the story, developing a picture book requires a constant evaluation of what is essential for the narrative. The language must be at just the right level for a five-year-old to comprehend, and Behar wrestled with how to share Sephardic heritage, both its lightness and its shadows, with younger audiences.

Despite the challenge of this task, she says, “I do feel that I have a responsibility to tell the Sephardic Cuban story as I know it. It’s the one that’s closest to me; it’s definitely a topic that I’ve studied anthropologically. With “Tía Fortuna” it was an opportunity to come back to that knowledge, but from the point of view of a certain innocence — trying to imagine the child I was, and a child today trying to understand this heritage.”

A new wave of cultural representation in children’s literature

Cover of “Tía Fortuna’s New Home,” written by Ruth Behar and illustrated by Devon Holzwarth (Random House Kids, 2022).

Representation matters a great deal to children, says Natalie Engel, a content executive at PBS Kids. She has been involved in creating groundbreaking series such as “Molly of Denali,” about an Alaska Native girl in the fictional town of Qyah, Alaska, and “Alma’s Way,” which depicts a young Puerto Rican girl growing up in the Bronx. “Alma’s Way” was created by Sonia Mazano, who is probably best known as Maria on “Sesame Street,” and the show — which is also available in Spanish — has been warmly received by the Latino community since its October 2021 debut.

“Studies show that when a child sees a positive representation of themselves, their community, their culture, or their race, it has such an impact on not only their self-esteem, but also their engagement and their ability to learn,” she says.

When portraying under-represented communities, Engel and her team aim for authenticity on every level. They often draw on the lived experiences of people in the writing room, which for example led to “Grandpa’s Drum,” an episode of “Molly of Denali” that emphasizes intergenerational relationships and traditions.

Engel, herself a mother of two young children, sees this as an exciting time for increasing the diversity of children’s content across different platforms: “Media is a great jumping-off point for conversation and for a shared experience. That’s why it’s great to see so many more kinds of ways in, even if it’s not a character who is representative of your experience.”

Perhaps, as Engel suggests, we are at an inflection point in the broader cultural landscape; the inclusive approach practiced by PBS Kids may become more achievable for heritage institutions in media and publishing. Yet there is much more work to be done to foster inclusivity, both generally and within Jewish children’s media, which, despite an increasingly diverse global Jewish community, skews almost completely towards Ashkenazi cultural depictions. “Tía Fortuna’s New Home,” with its vibrant synergy between Jewish and Latin cultures, is positioned to showcase a Sephardic family for a new generation of readers — and to inspire a new generation of writers, too.

Illustration of young Fortuna in Havana from “Tía Fortuna’s New Home.” Illustrated by Devon Holzwarth (Random House Kids, 2022).

While she hopes that Sephardic audiences will embrace “Tía Fortuna,” Behar also imagines a larger readership — particularly because there are so few Sephardic-themed books for children. She notes, “It’s a heritage that’s endangered in the way that many other languages and cultures are. Showing this diversity of Jewish culture is important as well. The goal is communicating the culture for one’s own culture, but also sharing it with others so that it doesn’t become completely insular.” Having recently attended the Latinx KidLit Book Festival, Behar aims to keep celebrating cultural commonalities with the Spanish-speaking world.

Reflecting the unique Ladino dialect of South Florida

A critical part of Sephardic heritage which is represented in Behar’s new book is Ladino (Judeo-Spanish or Judezmo), the ancestral language that Sephardic Jews carried with them when they fled the Iberian Peninsula in the fifteenth century. The dialogue in “Tía Fortuna” includes phrases that are particular to Ladino’s unique makeup, like mazal bueno (good luck, a combination of Hebrew and Spanish).

As a Ladino student myself, I paid attention to the language layers in Behar’s book and noticed the appearance of both Spanish and Judeo-Spanish. This reflects the Sephardic community of South Florida, particularly in Miami-Dade County, says Bryan Kirschen, Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Linguistics at Binghamton University. Kirschen is one of very few sociolinguists to have studied the Judeo-Spanish spoken in Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, and Broward counties. Kirschen analzyed how contact with Cuban Spanish influenced South Florida Ladino speakers and concluded in a 2019 article that “Sephardim have continued to preserve a variety of Spanish unlike any other in the area.”

In the broader picture of documenting Ladino for future generations, what is the potential value of a picture book that includes Ladino words and Sephardic folkways? As a language activist fully aware of Ladino’s endangered status, Kirschen believes that children’s literature could play an important role.

He says, “New works about Sephardic life serve a number of important purposes; they demonstrate that there is no one way to be Sephardic or even speak (Judeo-)Spanish. Such resources provide a toolkit for audiences, in this case younger ones, bringing oral and written practices to life. This is particularly meaningful for Sephardic children, many of whom navigate their cultural and linguistic heritage from an early age.” Like Engel, he believes in the long-reaching impact that representing a community, in all of its specificity, can have on young people.

A memento of Miami’s past and present

Miami’s Champlain Towers before the collapse in 2021 (Wikimedia Commons).

Incorporating Spanish, as well as Judeo-Spanish, directly into the story of “Tía Fortuna” was one way for Behar to accurately depict the distinctive texture of life among the Cuban-Jewish community in Florida, an area that she knows well. The Seaway where Tía Fortuna lives in the book was a real-life Miami residence near where Behar’s aunt lives, built in the 1930s and consisting of a group of two-story apartments; it is located near the site of the recently collapsed Champlain Towers. Just as in her book, the Seaway is slated to be demolished, with a luxury development to be built in its place.

“It was important to me that there was a documentary aspect to the book, that the Seaway be realistic,” Behar explains. “I think the book is going to be meaningful for people in Miami because of that.” She sent photographs of the building to her illustrator, with whom she closely collaborated to bring authenticity to all aspects of the illustrations.

Attentive readers may notice that Behar dedicated “Tía Fortuna” to her granddaughter, who was born last year just as she was wrapping up work on the book. She plans to write another book specifically for her first grandchild, reflecting, “A large part of this is the power of stories, the power that stories have for us both when we’re young and when we’re older. Stories are really the way we pass on heritage, and the way we share our heritage.”

With this beautifully realized book, a piece of Behar’s family history in Miami, and a symbol of a bygone era on the Florida coastline, will be memorialized forever. “My home will be a memory,” Tía Fortuna gently tells Estrella, who is understandably upset that the lovely pink casita will be destroyed. At the end of the book, she presses the casita key into Estrella’s hand, echoing the gestures of generations of Sephardim who have held onto pieces of the past, crossing borders and starting over, writing letters and speaking Spanish, with hearts full of esperanza — hope.

Listen to Ruth Behar at the University of Washington

-

Sephardic Places: Loss and Memory, 2015 Stroum Lecture

-

Sephardim: Longing and Reinvention, 2015 Stroum Lecture

Related Event: The University Book Store will host Ruth Behar and Hannah Pressman for a conversation about “Tía Fortuna,” Sephardic children’s literature, and more on Thursday, February 17th at 4:30 pm Pacific. RSVP for this virtual event.

Hannah S. Pressman is the Director of Education and Engagement at The Jewish Language Project, and writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (Koç University Press/University of Chicago Press, 2021). She is currently at work on “Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey,” a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Hannah S. Pressman is the Director of Education and Engagement at The Jewish Language Project, and writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (Koç University Press/University of Chicago Press, 2021). She is currently at work on “Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey,” a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.