Remembering Cuba with Pictures

Cuban-born anthropologist Dr. Ruth Behar will give the Stroum Lectures at the UW on May 18 & 20.

For the anthropologist Ruth Behar, a picture is worth far more than a thousand words: it can recall a whole universe of memories and dreams.

Behar, a prolific Cuban-born scholar and writer based at the University of Michigan, has both Sephardic and Ashkenazic roots. Her father’s parents immigrated from Turkey to Cuba in the early twentieth century. They were part of a wave of Sephardic immigrants fleeing the destabilizing Ottoman Empire, the Balkan Wars, and the prospect of conscription in the Turkish army. Her father’s side of the family spoke a combination of Ladino and Cuban Spanish.

Behar’s maternal grandparents, on the other hand, came from Poland and Russia. The Ashkenazic immigration to Cuba began in 1921, as anti-Semitism in Europe crested. Dwindling economic opportunities and strict immigration quotas in the US made Cuba an appealing destination. While Jews arrived from Germany, Hungary, and elsewhere, it was the Polish Jews whose presence made the most lasting impression on Cubans: to this day, polaco [Pole] is the word Cubans use to designate anyone Jewish, and el idioma polaco [the Polish language] is the Cuban name for Yiddish.

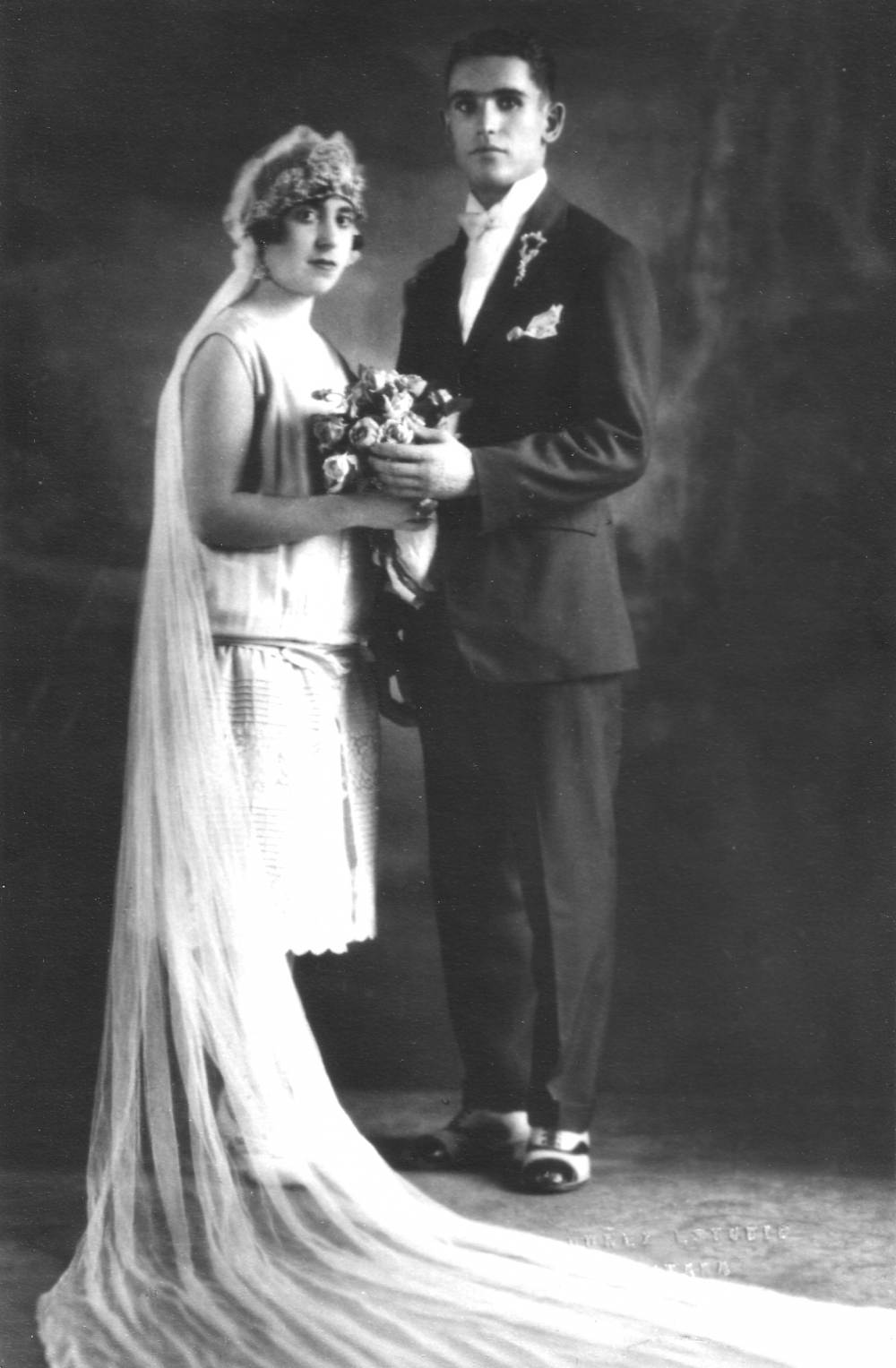

Ruth Behar’s paternal grandparents came from Turkey and were married in Havana. This photograph dates from the mid-1920s.

The black-and-white picture to the left, of her grandparents’ Havana wedding, represents that long-ago era of immigration and cultural transition. Behar explains its significance for her family’s Sephardic history: “This photograph is the only image I have of my paternal grandparents when they first arrived in Cuba from Turkey. They were young and full of dreams. I love my grandmother’s extra-long veil, worn with the knee-length 1920s drop-waist dress. My grandfather looks dashing in the two-tone shoes. They both have such dark mysterious eyes that seem to carry memories of Spain and Turkey.”

The story behind the handsome newlyweds in this photograph contains some unique details, but also connects to the collective experience of many Turkish Jews at the time. Behar elaborates: “My grandmother was Rebeca Maya Shalom and my father Isaac Behar Mizrahi. They both arrived in Cuba in the mid-1920s. They were from the same fishing town of Silivria (or Silivrí) near Istanbul, but they met in Havana. Many from the town of Silivria found their way to Cuba and there was even an association in Havana that honored that memory. My grandfather arrived first with his family. My grandmother came afterward, on her own. She left behind her parents and sisters in Silivría. She had an uncle in Havana who took her in. She played the oud and sang and the legend goes that her playing and singing seduced my grandfather. But after they married and had four children, she never played the oud again. They lived in a tenement in Havana, what is know as a ‘solar,’ where many Turkish families settled. My grandfather worked as a street peddler and my grandmother took care of the house and the children. Their apartment (which remains intact today) was within walking distance of the oldest synagogue in Cuba, the Sephardic synagogue, the Chevet Ahim, which was founded in 1913 on Calle Inquisidor (curiously enough!).”

“Having Heart in What I Do”

Behar interweaves the history of Cuba with her own family’s narrative in her ground-breaking memoir, An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba (2007). And it is in this book that Behar’s special relationship with photographs becomes clear. As she writes in the book’s introductory essay, “Our family moved from Poland and Russia and Turkey to Cuba in the 1920s, and from Cuba to Israel to New York to Miami in the 1960s and 1970s. And the photographs traveled with us. In those days, photographs were made to last and they withstood our uprootings with hardly a rip or a tear. . . . these pictures were a substitute for the Cuba I longed to see with my own eyes but couldn’t.”

The pictures Behar’s family managed to bring with them when they left Cuba became the cherished repository of her attachment to a place she couldn’t remember herself. A child of nearly five when her family left the island for New York, she later found herself wishing she could locate her “lost childhood” and wondering if her family’s few decades in Cuba had all been a dream. The quest to understand her own family’s archive, and to document all the threads of Jewish life left in contemporary Cuba, drove Behar to visit the island dozens of times in the last three decades. In the resulting book, An Island Called Home, there is a striking number of photographs of Cuban Jews holding their own family photographs–displaying with pride, and some visible sadness, the precious traces of the past.

Behar’s expertise on Cuba has made her a sought-after voice in the wake of the recent diplomatic thaw between Cuba and the United States. (This blog post includes links to some of her most recent media appearances on the subject.) Her body of work also includes vital contributions to the field of anthropology, such as The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart and Translated Woman: Crossing the Border with Esperanza’s Story. In addition, she is a respected writer of fiction, poetry, and personal essays, with contributions to several anthologies. This multi-dimensional output has earned Behar numerous accolades, including a MacArthur Genius Award and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

In a recent conversation, Dr. Behar reflected on how she allows herself to play a role in the ethnographies that she writes: “For me, having heart in what I do has always been important. Writing about how I’ve been moved, and wanting to move my readers to feel something as well. That’s been a central part of my work.”

A Language of Home

Finding “a language of home” in the modern era of global migrations is a theme that pervades Behar’s scholarly work, and it is the organizing principle behind “Dreams of Sefarad,” her upcoming Stroum Lecture series at the University of Washington (May 18 & 20). Behar will explore the ideas of exile and loss as the core of Sephardic identity since the expulsion from the Iberian peninsula in 1492. She plans to move between cityscapes in several countries, including Istanbul, Havana, Miami, New York, and Seattle, which are all linked by their relationship to the sea. Much like her anthropological research, the lectures will span genres: history and ethnography will be central, but she will incorporate poetry, song traditions, and personal essays as well. While the lectures will be in English, they will interweave Spanish and Ladino.

Image from Ruth Behar’s documentary film about Cuba, “Adio Kerida” (Goodbye Dear Love).

Behar was curious about her Sephardic heritage as she was growing up in New York in the 1960s and ’70s, but found that Ashkenazi identity dominated American Jewish culture. In a media landscape populated by Woody Allen and Philip Roth, there weren’t a lot of Sephardic representations she could relate to. A turning point came in the 1990s, when she read Victor Perera’s Rites: A Guatemalan Boyhood (1994). Perera’s memoir of growing up Jewish in 1940s Guatemala inspired Behar to focus on her Sephardic identity: she produced and directed Adio Kerida (Goodbye Dear Love, 2002), a personal documentary wherein she returns to Cuba, determined to learn about the everyday lives of the Sephardic Jews remaining on the island.

She says, “When I made my movie I wanted to know what contemporary Sephardic Jews look like. There wasn’t a character in media we could identify.” However, now the Jewish cultural landscape is far different: “We’ve seen a growing migration of Latin American Jews to the US from Venezuela and Argentina. Now the idea of multicultural Jews is more present. Now we’re much more interested in global Judaism and exploring how Jewishness can be diverse too. But when I grew up, it was much more limited.”

Behar is extremely interested in Seattle’s Sephardic community, one of the largest in the country–and one of the last places where Ladino is still spoken. As part of her preparations for the Stroum lectures, she visited Seattle in December, spent several days with community members, and even located some Behar cousins.

What was Behar’s own “language of home” growing up? She replies, “For me, the Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and the Cuban elements came together in an interesting way. I grew up in a polyglot environment, but Spanish was the unifying language of our family. It was the language of home.”

As someone who has been researching my own Sephardic roots for over a decade, I couldn’t resist a last question: what suggestions does Professor Behar have for people who are interested in probing their family’s history, but lack the proper anthropological tools–or even the basic facts behind their family’s mementos? She offers the following meaningful advice: “Old family photographs offer an imaginative window into the lives of our ancestors and are a precious resource, even when we don’t have the stories to go with them. I think just being able to look into the eyes of those who came before us and see the hope and expectation they brought as youthful immigrants is deeply meaningful and uplifting. Offer them your gratitude. Light a candle in their memory. And ask them to give you strength on your journey.”

Editor’s Note: Click here for more information & to RSVP for Ruth Behar’s lectures on May 18 and 20.

Leave A Comment