Runner up, student category – 2024 “Muestras Konsejas” essay competition. See all winning essays.

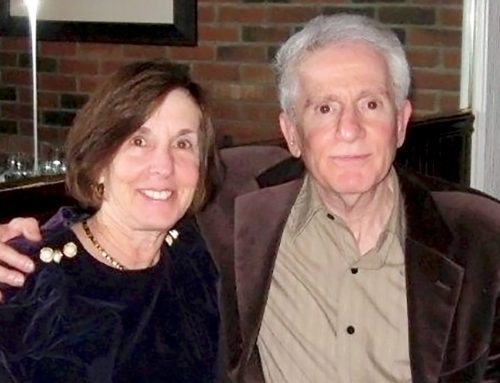

A horse-drawn carriage on Buyukada (“Big Island”), an island close to Istanbul

By Nesi Altaras

Nesi Altaras

Until I moved to the U.S. at 18, I lived my entire life in Istanbul, my city of birth. Ours was the largest Sephardi community that continued an uninterrupted existence from Ottoman times to the present and in Istanbul, to be Jewish was to be Sephardi. And to be Jewish in early 2000s Istanbul meant being assiduously traditional while also being extremely practical. Our execution of tradition came not necessarily from cherished belief but simply because it is tradition. This was especially evident at weddings, brit mila, and funerals, where I would ask “Why did they do that?” and the answer from my parents was simple “That’s what is done.” But when it came to daily life, we were quite flexible. When the way things had been done got in the way of the most pragmatic way of going about our lives, doctrine could easily be elided. We never went to synagogue on Kipur and when I asked why not, my dad would wisely say that since the nearest synagogue was not walking distance, we would have to drive, and if we drove to synagogue to hear the shofar, we would actually be breaking the rules of that day. Hence, it was better not to go at all. Never mind that we spent the day at home watching movies.

As a child, I spent my summers on Buyukada, an island off the coast of Istanbul, where Jews would flock over the summer. To this day, it is one of the only places you could overhear Ladino on a street. On this quasi-Jewish island, we children enjoyed freedoms that we could not conceive of in the city. Since there were no cars and friends everywhere, we biked all over this rock called “Big Island” in Turkish, which was actually only 13 kilometers around, only the north half of which had houses. After spending our day at the beach or at a pool and playing endless rounds soccer, some of us prepubescent boys would go to the synagogue once or twice a week. The island synagogue Hesed LeAvram was an imposing and decorated building in bright yellow. Not that anyone could see it – it was covered by high metal walls and topped with barbed wire. Even the street was cut off on both sides by metal gates that forced us to get off our bikes and lock them to a tree a few steps away. Despite its invisibility, the kal was enough of a landmark that people would use it to describe addresses: “The Halfons live one street up from the kal.”

On some summer afternoons, there would be Talmud Torah at this kal. This Talmud Torah was not a full-fledged school like in the days of our great-grandparents but a series of weekly classes to acquaint us with the basic stories of Jewish texts, the Hebrew alphabet, and key concepts of Judaism. Kids of different age groups would sit on either side of the courtyard, past the blast-proof doors at the front, or in different sections of rows inside. The amores were men in their twenties, who (looking back) I hope were paid at least a little for their time trying to teach unruly kids on their summer break. I was one of those kids. My mother, as traditional-but-not-religious as any sefardita could be, directed me to go to Talmud Torah, and for a few summers I did. The little I learned in the way of Hebrew letters in those afternoons served me well all the way up to my bar mitzvah.

During one of our classes at Talmud Torah, sheltered from the heat inside the air-conditioned kal, our amore outlined for us kids the rules of kasherut. He told us to follow those rules and good little Jew that I was, I went home and declared to my family that I was now going to keep kosher, “because that’s what we are supposed to do.” It is surprising now to think such a paltry explanation made sense to my child self when no one I knew kept kosher. The abstract Jew kept kosher, but the actual ones surrounding me did not. The abstract Jew went to services, the living ones did not. There seemed to be a normative Jewish way to do things and then a practical way, our manner of being Jewish. Only in retrospect do I recognize this mode as Sephardic or specific to Turkey. My childhood attempt at keeping kosher was not a rebellion or the result of a search for fulfillment. The declaration that I was going to keep kosher was still abstract, not tested by any real-life situation. Clearly sensing that this commitment was not going to last too long, my mother heartily agreed, “Of course you can keep kosher if you want. Good for you.” She did not commit to keeping kosher herself but was happy to let me do as I saw fit.

Shortly after my announcement of Kosher Status we sat down for dinner, which was kabak dolmasi (stuffed zucchinis). The zucchinis on that side of the ocean have lighter green skins, which we use to make kashkarikas, a cold, sour appetizer that uses up zucchini peels. In the summer, instead of lemon, my grandmother would put sour green plums in her kashkaras that she collected from the plum tree in the garden of her island home. After being peeled and the peels used productively elsewhere, the zucchinis were scooped out and stuffed with filling of meat mixed with rice. The zucchinis were arranged to stand upright along the side of the pot and their insides were dumped in the middle. Covered with water and tomato sauce, they would cook until the rice grains poked out a bit like little meerkats.

These dolmas, like almost any food in my opinion, go great with yogurt. So after getting my plate, I naturally asked my mother to pass me the yogurt. I was shocked to hear “Are you sure?” My mother told me that I could not have yogurt: “If you’re keeping kosher, you can’t put dairy on meat.” That meant all the food that required yogurt from manti to iskender would be left dry. This was a scary thought. It was only a few hours before that I had been taught the precepts of Jewish dietary law. However, that had only been in the abstract – sure I’ll agree to any rules that we are supposed to follow because it is tradition. Outside of mealtime I had agreed to not eat dairy and meat together. But at dinner it became very concrete, and the stakes were extremely high. Yogurt was at stake. I made up my mind quickly: “I’m not keeping kosher anymore!” And heaped a mountain of yogurt on my dolmas.

Presented in partnership with the Sephardic Brotherhood of America, the 2023-2024 “Muestras Konsejas” writing contest opened a new space for the telling of Sephardic stories. Writers were asked to share an original work of prose (fictional or memoiristic) that gives voice to the experiences of the Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jewish communities (whether from family lore, lived experience, community heritage, life stories, etc.). Stories from all over the world were read by an expert panel of judges, who selected four finalists (across both “General” and “Student” submission categories) as the inaugural winners.

congrats to all the participants sweet idea so much talent given to us thanks to all of them keep it coming Alberto (abramiko behar)