Cheers to 40 years: The crowd mingling during cocktail hour at the Harley and Lela Franco Maritime Center during the Stroum Center’s 40th Anniversary Gala. May 13, 2014. Photo by Meryl Schenker Photography.

On the 13th of May, the UW Stroum Center for Jewish Studies hosted a Spring Gala to celebrate the 40th Anniversary of Jewish Studies at the University of Washington. The event provided Jewish Studies faculty, staff, students, and graduate fellows the opportunity to meet the Seattle Jewish community that so generously supports our program. It was a night full of incredible stories, sharing experiences, and good conversations.

To make it easier for the community to mingle with the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellows, each fellow was assigned to an interactive station. As a Graduate Fellow from Turkey, who works on politics in Arab countries and Israel, my responsibility was to accompany the station where a type of hard liquor called arak was being displayed and served, and to give Gala participants some historical context about the unique geographic and political origins of this drink.

Arak is an anise-based distilled hard liquor that has between 45 and 60% alcohol. There is a very similar drink in Greece called ouzo, and likewise there is a drink called raki in Turkey. More than just a place to clink a glass and say “l’chaim,” my Gala station became a meeting point of stories, histories and memories from different parts of the Near and Middle East region. The starting point of almost every conversation I had that evening was the arak station’s introductory sign: “Did you know that the most famous raki (anise aperitif) in the Ottoman Empire was manufactured by a rabbi?” This famous raki-maker of the Ottoman Empire was a man named Rabbi Meir Jacob Nahmias (1803-1887), who was living in Thessaloniki, which was then a city of the Ottoman Empire.

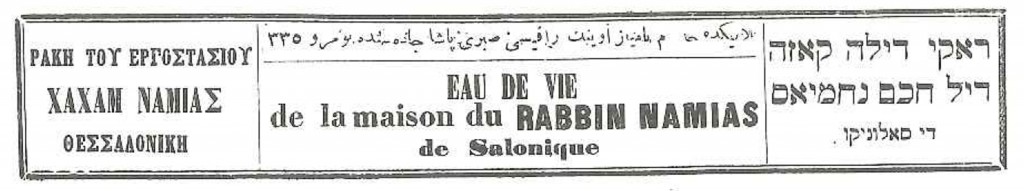

Advertisement for Rabbi Namias’ famous raki, an anise liquor popular in the Ottoman Empire. The languages on the ad (left to right) include Greek, Ottoman Turkish, French, and Ladino. From the Ladino newspaper “El Avenir” of Salonica, 1900.

Rabbi Nahmias is a challenge to the way we imagine identities today. After the rise of nationalism and nation states, and the deepening of religious and ethnic divides, we tend to imagine ethnic-national identities as de facto and fixed concepts. Rabbi Nahmias wore so many different hats that he forces us to reconsider what identity is, and how fluid it can really be. He was a Jewish Chief Rabbi, he was an Ottoman subject, he was from Thessaloniki—and he was making premium raki (that’s the Turkish name of arak)! More than a century after his death, Rabbi Nahmias opened the door for us, at this year’s Jewish Studies Gala, to taste and discuss this liquor, whose story reflects the cross-cutting paths of Jews, Muslims, and Christians, as well as Arabs, Israelis, Turks and Greeks. Rabbi Nahmias’ story helped us to think and comment on the limits and intermingled nature of Jewish identity, as well as to share incredible family stories of Sephardic members of the Seattle Jewish community, many of whom came from the Ottoman Empire to Seattle.

Rosa Eskenazi was a famous Jewish-Greek singer.

Rabbi Nahmias is not the only figure who reminds us to consider how artificial and built-up our perception of the world and identities may be. Ethnic, linguistic and religious combinations that seem to be impossible today were once natural for many people; Roza Eskenazi was one of them. The famous Jewish-Greek rebetiko singer Roza Eskenazi was born in Constantinople (Istanbul) in the mid-1890s. Her exact date of birth is unknown as she hid it throughout her career. Shortly after the turn of the century, Rosa and her family moved to Thessaloniki. Her incredible voice was first discovered by the owner of the local tavern.

Eskenazi’s life was full of ups and downs. She fell in love; she lost her husband; she left her son to the nursery to maintain her career as a performer. However, she never stopped singing and ultimately became a famous rebetiko singer in the tradition of Greek urban folk music. As a Jewish Ottoman woman born in today’s Turkey and living in today’s Greece, Roza Eskenazi was speaking and singing in both Turkish and Greek. Her music features tunes from Jewish, Turkish and Greek music.

Eskenazi’s most important contribution was her recording and making popular the Smyrna (Izmir) school of rebetiko. She made this almost- forgotten musical style a part of the popular culture. Before the outbreak of World War II, Eskenazi toured the Balkans and the Near East. She became a bridge between people by connecting them to each other with the soft tunes of her music. One of her most famous songs is “To Kanarini” (The Canary), which she recorded in 1934. Here is the famous “To Kanarini,” for all the arak and rebetiko lovers, for everyone thinking about their mingled identities and our roots in the past.

Leave A Comment