By Makena Mezistrano

On December 5th, 2019, nearly 400 students, faculty, and community members gathered in the HUB Lyceum for the seventh annual International Ladino Day. This year’s program traced Sephardic life cycle customs from the Ottoman Empire to the Pacific Northwest and was inspired by a refran, or Ladino saying: de la fasha asta la mortaja. While in English this concept is expressed idiomatically as “from the cradle to the grave,” the Ladino version invokes two garments and celebrations at the beginning and end of life unique to Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire: “from the swaddling cloth to the shroud.”

Prepared by expecting mothers and their families and friends at a joyful celebration known as the kortar fashadura, the fasha is the swaddling cloth wrapped around a newborn baby. Similarly, the mortaja is the burial shroud that envelopes the deceased — this, too, is prepared while a person is still alive at a similarly festive event known as the kortar mortaja.

Under the theme of life cycles, Ladino Day 2019 featured multigenerational performances of Ladino songs by the Ladineros, Seattle’s long-standing Ladino conversation group whose members are among the last generation of native Ladino speakers, and the recitation of a Ladino speech by Anna Jacoby, a sophomore at the Seattle-area Northwest Yeshiva High School.

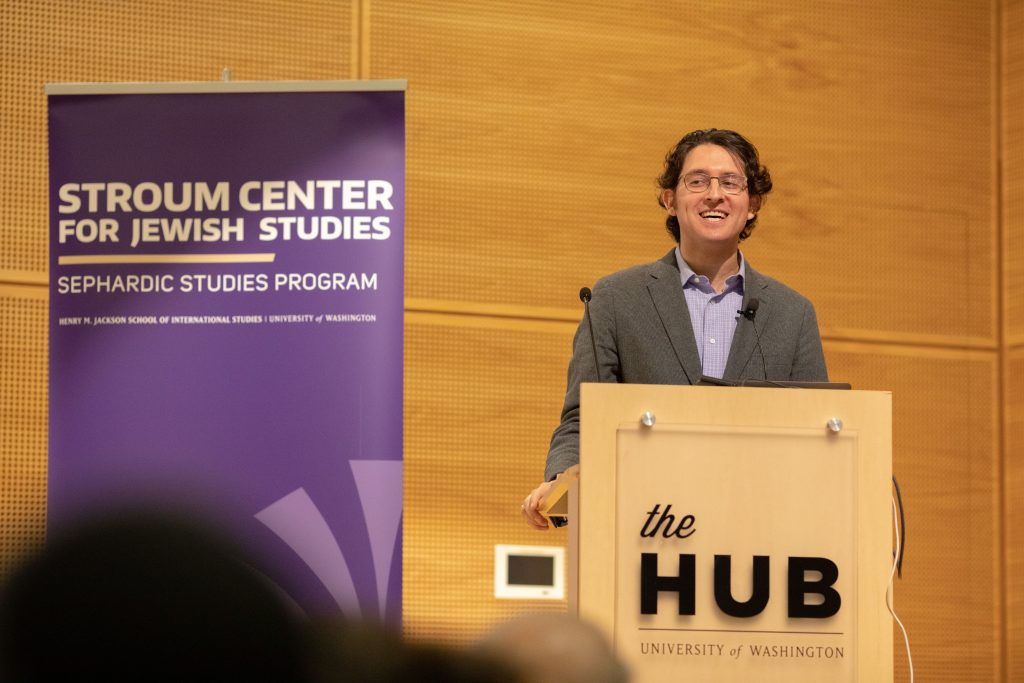

Their presentations were interspersed throughout a multimedia talk by Dr. Devin Naar, Chair of the Sephardic Studies Program, who incorporated digitized artifacts from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, including handwritten manuscripts, photographs, audio, and video footage. These artifacts — and many more — were also curated into an online digital exhibition titled Exploring Sephardic Life Cycle Customs developed by the Sephardic Studies Program and unveiled as part of Ladino Day.

Dr. Devin Naar, Sephardic Studies Program Chair.

“At one, I was born”: A Sephardic baby-naming ceremony

The Ladineros then took the stage to frame Dr. Naar’s talk, beginning with an enthusiastic rendition of the popular Ladino folk song A la una yo nasi (“At One I was Born”). Each of the four lines of the song’s refrain references a defining moment in the life cycle, including birth, coming of age, engagement, and marriage.

The song is also significant because while many people assume its lyrics were transmitted over the centuries since the expulsion of the Jews from Spain until the present, Dr. Naar drew on the latest ethnomusicological scholarship by professor Edwin Seroussi at Hebrew University to suggest that it is actually a relatively new song in the Ladino repertoire, learned by Ottoman Jews from Spanish troubadours who traveled the Balkans in the late 19th century.

Beginning with the first line of the refrain — A la una yo nasi (“At one, I was born”) — Dr. Naar started with birth. While Jews everywhere observe many important rituals after a baby is born, including berit mila (circumcision) and pidyon ha-ben (a special ceremony for newborn sons), Dr. Naar highlighted the fijola , more commonly known as zeved ha-bat — a naming ceremony for a baby girl that originated in medieval Spain. Accompanying this segment of Dr. Naar’s talk, the Ladineros sang a Ladino rendition of Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs) traditionally sung at a zeved ha-bat.

With photos and video footage of two Seattle Sephardic baby namings from the 1950s and 1980s, the audience got a taste of what a traditional Sephardic zeved ha-bat would have looked like; most notably, it took place in the home with lots of singing and dancing. In fact, all of the then-babies in each video were present at this year’s Ladino Day: twins Marlene and Charlene Souriano, and Miri Azose Tilson.

“At two, I grew up”: The bar mitsva

The next line of A la una is somewhat open ended: A las dos me engrandesi (“At two, I grew up”). In the context of major life cycle events, Dr. Naar focused in on the bar mitsva — the Jewish coming of age ceremony which, until recently, was reserved only for young boys.

In Ladino, the bar mitsva was known as kumplir minyan, which means “to complete the minyan” — a reference to a young boy now being able to count in a quorum of ten men for prayer known as a minyan.

Anna Jacoby reads from Morrie Capeluto’s 1944 bar mitsva speech in Ladino.

For those who have attended a bar or bat mitsva today, the speech given by the young boy or girl is one of the highlights. Yet in the Ottoman Empire, the bar mitsva speech was a late innovation, an adaptation from an Ashkenazi practice at the start of the twentieth century, and only became commonplace in the Seattle Sephardic community in the 1940s. To learn more check out our new digital exhibition!

When bar mitsva speeches in Seattle became en vogue, they were primarily delivered in Ladino. Anna Jacoby brought this time back to life at Ladino Day by reading selections from Morrie Capeluto’s bar mitsva speech in Ladino. Capeluto was a member of Ezra Bessaroth, and his curtain factory in Seattle’s Central District neighborhood was the original meeting place for the Ladineros when the group initially formed.

Part of my role for Ladino Day this year was to rehearse and prepare with the Ladineros and with Anna. With the Ladineros, I was among a group of the last generation of native Ladino speakers for whom Ladino was a familiar language, and with that familiarity comes a certain flexibility. During rehearsals the Ladineros not only learned and practiced their songs, but they also debated the pronunciation of the lyrics and the cadence of the tune. Sometimes they even revised the lyrics to make them easier to sing.

When I spent time practicing with Anna, our focus was necessarily much different. Until our first session nearly a month before Ladino Day, Anna had never read or spoken Ladino before. Anna’s great-great-grandfather, Jacob Policar, was one of the first Sephardic Jews to come to Seattle in the early 20th century, but his native language was almost alien to her.

As part of our practice sessions, we needed to adopt firmer rules than the Ladineros when it came to pronunciation and word choice: Which letters made which sounds consistently? Where is the accent on this word? Through her diligent efforts, by Anna’s final performance, she was reading Ladino with greater ease.

“At three, I was engaged; At four, I was wed”: Sephardic wedding contracts

A la una ends with marriage, describing both engagement or falling in love (depending on the version of the song), and the wedding. For this section of the presentation, Dr. Naar focused on the Sephardic practice to illustrate and illuminate the ketuba — the Jewish wedding contract exchanged between husband and wife on their wedding day.

The Sephardic Studies Digital Collection (SSDC) retains four ketubot from Tekirdag, formerly known as Rodosto or Rodoschik, a city on the shore of the Sea of Marmara in Turkey. This is the largest collection of ketubot from this region anywhere in the world!

Sephardic ketubot are unique from their Ashkenazi counterparts for many reasons, explained Dr. Naar, relying on the expertise of Shalom Sabar, a professor at Hebrew University. For one, Sephardic ketubot not only included the city in which the wedding took place, but they also referenced its proximity to a body of water. The imagery and iconography included on the ketubot, such as the start and crescent — symbols of the Ottoman Empire and of Islam — and of the tughra, the seal of the sultan — reveal how deeply imbedded Jews were in the Ottoman context, as Dr. Naar first explained in a previous essay.

The ketubot also included a unique monogamy clause: although Ashkenazi rabbis banned polygamy in the 11th century, it was still practiced by Jews in certain parts of the Muslim world. The ketuba thus served as a way for Sephardic Jews to distinguish their practices from those around them — a documentation that proved vital when immigrating to the United States where the practice of polygamy could prevent entry.

Dr. Naar’s display of the ketubot in the SSDC was accompanied by two songs from the Ladineros about a man courting a woman: Dame la mano palomba (“Give Me Your Hand, Dove”), and A la boda i la biskocho (loosely translated as “From the Wedding to the Reception”).

The Ladineros, Seattle’s Ladino conversation group, performed four songs at Ladino Day.

Beyond A la una: The cemetery

A la una captures many important life cycle moments, but it is incomplete: the song does not reference death. Nonetheless, Sephardic Jews observed many rituals related to death and burial — like the kortar mortaja referenced above — and the cemetery was also a central place in Sephardic communities in the Ottoman Empire.

Dr. Naar described how although associated with death, the cemetery served as a place of life, known euphemistically as the bet ahaim (“house of life”). He mentioned the niche employment opportunities that cemeteries offered, and how many of these roles were inspired by positions in neighboring Muslim cemeteries. To learn more about the bet ha-hayim, visit our digital exhibition.

The future of Ladino

Dr. Naar concluded with another Ladino refran: Si non ay kantadores, non ay sintidores (“If there is no one to sing, there certainly will not be anyone to listen”). At Ladino Day 2019, a diverse crowd had the opportunity to hear from the Ladineros — some of the last native singers of Ladino.

Joel Benoliel, the first Sephardic chair of the UW Board of Regents.

At the same time, a new voice emerged as a member of the younger generation engaged with the language. And there is more to come: As part of the introductory remarks at the beginning of Ladino Day, Joel Benoliel, Chair of the UW Board of Regents and a member of Sephardic Studies’ Founders Circle, shared an exciting announcement about the future of Ladino at UW: This summer, Dr. David Bunis from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem will be teaching a Ladino language course open to undergraduate and graduate students as well as the general public — a course which may inspire students to participate in what hopefully will evolve into more robust course offerings in Ladino.

Between the past generations and those yet to come, the Sephardic Studies Program looks forward to being the bridge that connects Ladino speakers of the past with Ladino listeners and speakers of the future.

All photos courtesy Meryl Schenker Photography.

Special thanks to the Ladineros for their enthusiastic performance at Ladino Day this year: Regina Amira, Vic Amira, Sylvia Angel, Isaac Azose, Solomon Azose, Kathie Barokas, Al Cordova, Jack Cordova, Janine Hasson, Dana Hasson McMullen, Al Shemarya, and Marlene Souriano-Vinikoor. Thanks also to long time members Ralph Adatto, Lilly DeJaen, and Morry Mochkatel.

Thank you to our cosponsors: The departments of Spanish and Portuguese Studies; Linguistics; History; Anthropology; the UW Libraries; the Turkish and Ottoman Studies Fund at the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations; Congregation Ezra Bessaroth; Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation; and the Seattle Sephardic Network.

Wonderfully informative and accurate review of the annual Ladino Day event this year. Bravo for a job well done! Merci Muncho to the UW staff; Prof Devin Naar, Ty Alhadeff and you Makena and muestro Maestro of the ladineros Isaac (Yitzhak ) Azose for preparing and organizing the event.