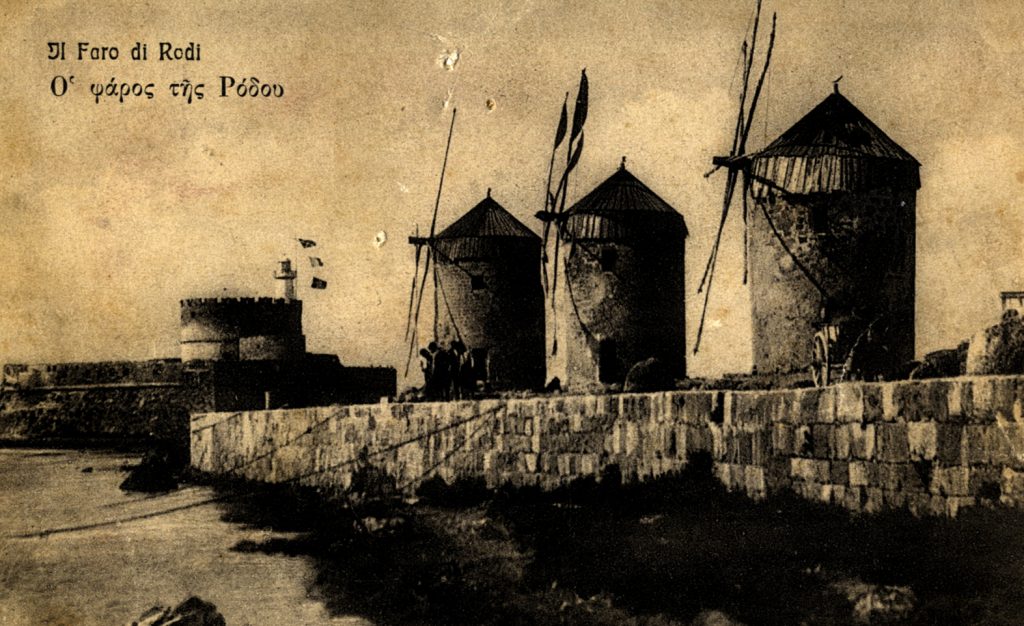

1920s postcard from Rhodes, featuring the island’s famous windmills, with Italian and Greek printed at lefthand corner. (ST00012, courtesy Kathie Barokas)

By Mimi Brown

A world shaped by economic woes, the precariousness of health, long stretches of time spent far away from family, and an unreliable postal system: These descriptions may resonate with our current moment of global pandemic, economic downturn, and political upheaval. But they also characterize the contents of a cache of letters exchanged among the Capeloutos and Shemaryas in the 1920s and 1930s. Dispersed between their native Aegean island of Rhodes, Seattle, and elsewhere, this extended Sephardic family experienced and reflected on the tumultuous period between the two world wars, a period bracketed by the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 and the lead up to the devastation of the Holocaust.

These family letters, written principally to and from women in the Capelouto and Shemarya families in their native language of Ladino, offer a strikingly rare and intimate portrait of the lives of Sephardic women through their own words. Like other scholarship that draws on unconventional or incomplete sources like family letters or material objects to piece together women’s lives throughout history, the case of the Capelouto and Shemarya women offers an invaluable opportunity to learn about their lives as they portrayed them to those they held dearest.

1920s postcard from Rhodes. The photo’s Italian label evidences the island’s transfer from Ottoman to Italian control in 1912. (ST00012, courtesy Kathie Borokas)

On Jewish Rhodes

In 1912, Italian forces seized the island of Rhodes from the Ottoman Empire, which had controlled the Dodecanese island since the sixteenth century. The resulting political and economic instability prompted many members of the Jewish community of Rhodes to emigrate, accelerating the birth of a modern Rhodesli Jewish diaspora that saw as many as half of the Jews of the island leave for new shores.

Young Sepharadi Jews whose ancestors had called the Aegean island their home for centuries began to leave Rhodes for Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. Those Jews who left could not have known the fate of their community: some twenty years later, the approximately 2,000 remaining Jews of Rhodes would perish in the Holocaust.

The family of Abraham and Estreya Capelouto

Like so many of the Rhodesli Sepharadim who left the island in the first three decades of the twentieth century for far-flung destinations across the globe, the paths taken by the children of the Rhodesli Jewish couple Abraham and Estreya Capelouto offer a sampling of some of the choices young Jews in Rhodes had in the 1920s and 1930s.

Photograph from Rachel Shemarya’s Petition for Naturalization, November 1941. Courtesy of Ancestry.com

Miriam, the eldest, married “Bohor” Aaron Menashe (so named because he was also the firstborn of his family), with whom she lived in Rhodes, along with her youngest sister, Leonora. Rachel, the second eldest, immigrated from Rhodes to Portland, Oregon in 1921, where she married Jack Shemarya, a fellow Sepharadi from Rhodes, on July 1, 1921, before moving to Seattle in 1922 and settling in to a home at the corner of 24th Avenue South and Yesler Way in Seattle’s Central District, once a center of Jewish life in Seattle for Ashkenazi and Sepharadi Jews alike.

Mathilda, the middle child, who lived in Rhodes when she exchanged letters with her sister Rachel and brother-in-law Jack in 1922, moved to Palestine shortly thereafter. Their brother Victor, the second youngest, emigrated to the Congo. As was true for the overwhelming majority of the Jews who remained in Rhodes during these years, both Miriam (Bohora) and Leonora tragically died in the Holocaust.

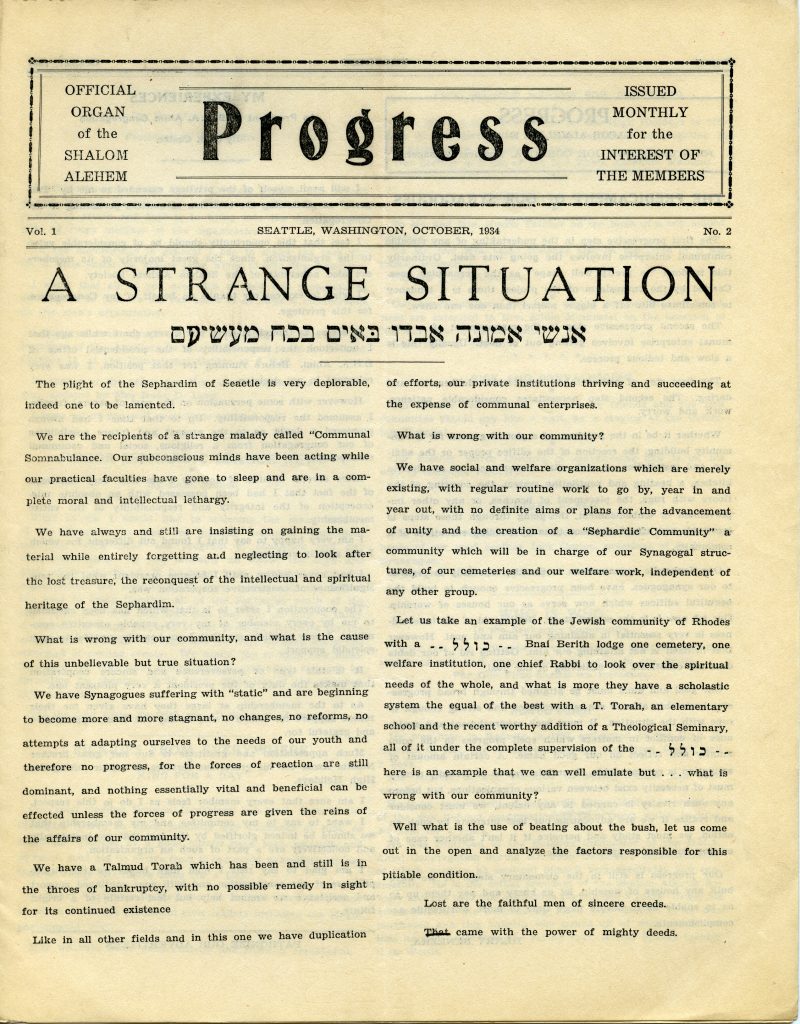

In this 1934 issue of “Progress,” a newsletter from Shalom Alehem – a now-defunct Seattle Jewish organization – writers plead for a merge between all Sephardic institutions in the city. (ST01298, courtesy Henry Benezra via Al Maimon)

Sephardic Seattle in the 1920s

Those who came to the United States following World War I encountered an economic recession that lasted until the summer of 1921. The United States economy recovered and boomed throughout the Roaring Twenties until the 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression. American Jews, like many Americans, experienced economic uncertainty and job instability.

In Seattle as well, many Jewish organizations struggled to pay their bills and keep their institutions open. The Sepharadi synagogues Congregation Ezra Bessaroth and Sephardic Bikur Holim attempted to merge institutions and share a building in order to save money and in order to achieve a sense of communal unity. (Though their merger ultimately proved unsuccessful, both congregations are thriving in the Seward Park neighborhood of south Seattle today.)

Family letters offer a glimpse into the lives of Sephardic women

This was the context in which Rachel Capelouto Shemarya left Rhodes and arrived in the United States. The letters she received from her parents and sisters back in Rhodes throughout the 1920s and 1930s provide a window into the lives of three generations of Sephardic women who lived their lives between Seattle and Rhodes and beyond. They contain their most frequent worries and fears alongside their greatest joys and a deep sense of caring. Through their own voices, it becomes clear that they were bound together by both their anxieties and their love for one another.

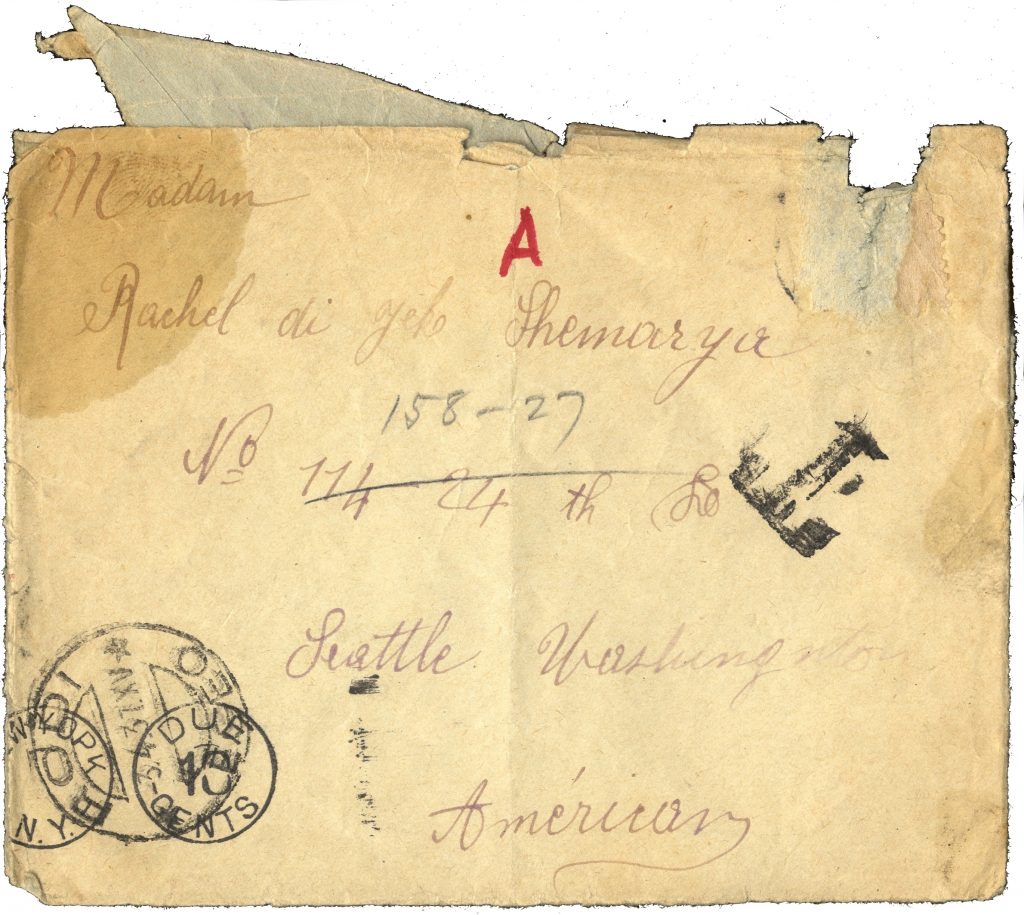

Envelope addressed to Rachel Shemarya at her Seattle address (ST01030-11, courtesy Al Shemarya).

The collection of letters left behind by these two families (intertwined by marriage) includes five envelopes addressed to Rachel and Jack with 29 pages of text handwritten by their family members in the Sepharadi cursive script traditionally used for Ladino, or soletreo. Each envelope includes several pages densely filled with messages from multiple family members in black or blue ink. Many of the letters were written on both sides of the paper or contain post scripts squeezed into the margins.

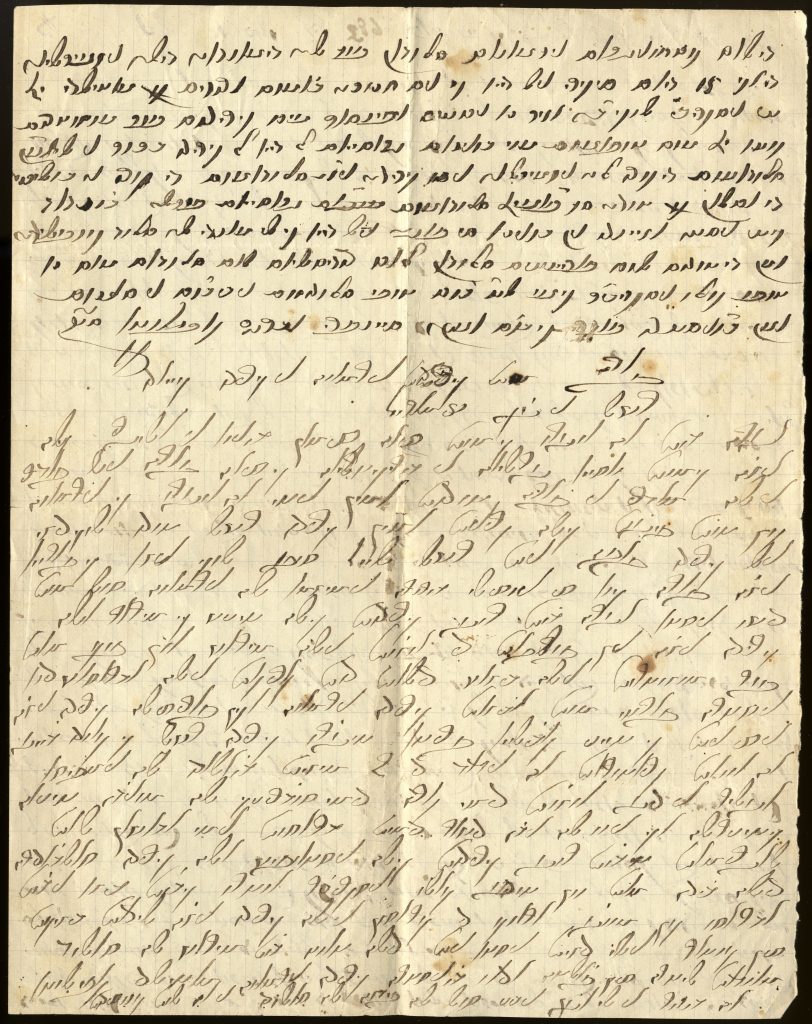

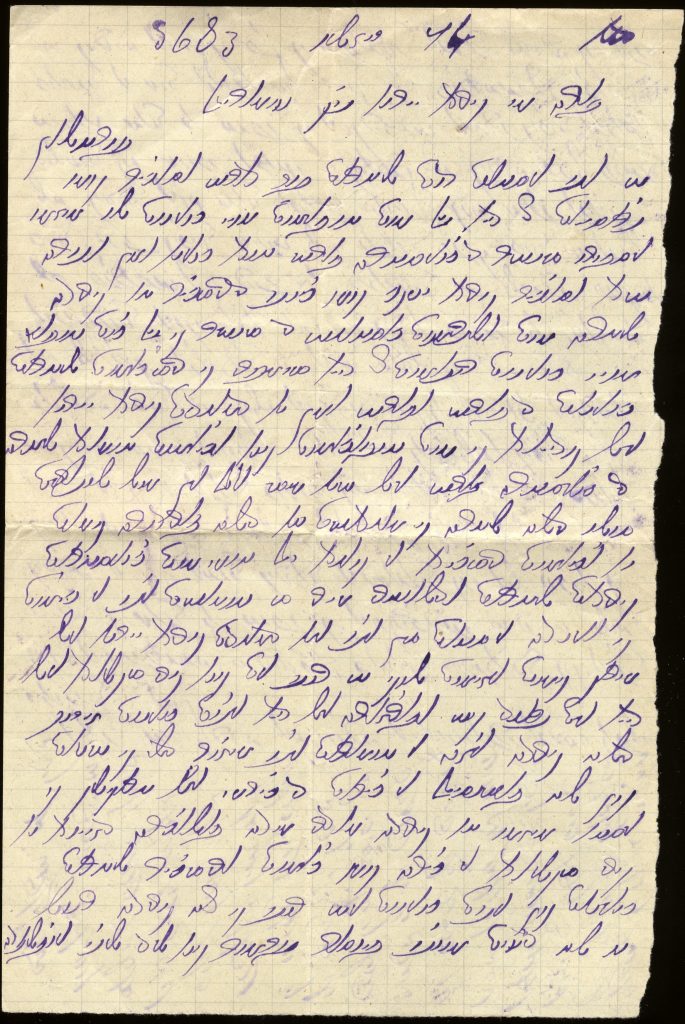

Letter from Mathilda to Rachel. Mathilda’s portion of the letter is in the lower half of the page (ST01030-07, courtesy Al Shemarya).

Mathilda Capelouto

The first envelope, addressed to Rachel in Seattle and postmarked from Rhodes on November 30, 1922, included a letter written by Abraham Capelouto, Rachel’s father, followed by a second letter from her sister Mathilda. Mathilda began her letter with a blessing, pepped with Turkish-derived terms, for Rachel, Jack, and their new daughter, Salva:

Agora vos auguro ke mos sea siman bueno i alegre la ija ke mos nasyo. Gurlia i bereketlia ke sea para el padre i la madre i para todos, amen. I te a oguro ke ermana kon tus petchos ke la krees, amen.

“Now my wish to you: May she be a good and happy omen for us, the girl who was born unto us. May she bring luck and prosperity to her father and her mother and to everyone, amen. And to you, my sister, I wish you that you make her grow with your breasts, amen.”

Mathilda’s letter emphasized Rachel’s power and responsibility as a nursing mother to “make Salva grow” with her own milk. She concluded her letter by beseeching Rachel and Jack, “to hide [from the evil eye] your dear Savior of life [Salva]” (vos rogo keridos ke la estanpesh a la kerida Salvadera de la vida).

Mathilda’s invocation of the evil eye, also known in Ladino as ayinara or ojo malo, linked her to generations of Sephardic women before her who had found meaning in this form of domestic practice and belief. The blessing she offered to her sister Rachel and her newborn niece also pointed to Mathilda’s sense of the realms of Sephardic women’s power and agency, ranging from their belief in unseen forces at work in the world to their physical bodies.

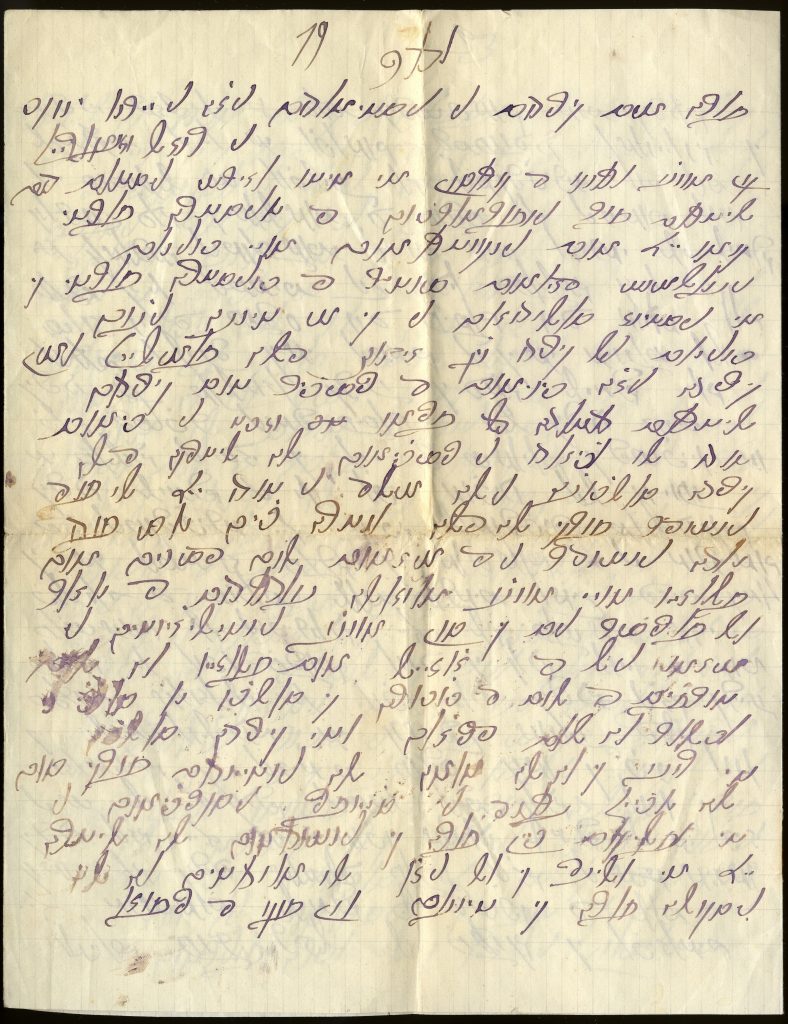

Letter from Estreya (dictated to Miriam “Bohora”) to Rachel (ST01030-10, courtesy Al Shemarya).

Estreya Capelouto

A second letter, dated only a few days after Mathilda’s, came from Rachel’s mother Estreya. Addressing Rachel’s husband, Jack Shemarya, Estreya had dictated her words to Bohora (Miriam), Rachel’s elder sister (quite possibly because Estreya herself was illiterate). Estreya recalled that upon opening a letter from Jack, “the first thing I saw was whether you got a job” (adelantre miri si tomates etcho). She continued:

I vimos ke aynda estas sin etcho. I no demandes kerido yerno el merak ke mos izimos…i te rogo ke a la kerida Rashel no la deshes muncho pensar pormor ke no le de leche enfligada a la kerida ija.

“And we saw that you are still without a job. Don’t ask, dear son-in-law, the sorrow that we had…for dear Rachel, do not let her think too much, so that she will not give her afflicted milk to the dear daughter.”

Once more, Rachel’s relatives signaled the power of her body. Estreya and Mathilda’s concerns about the ojo malo, stress and anxiety, and breastfeeding are reminiscent of the healing incantations (prekantes) that Sephardic women traditionally recited as a ritual prayer. These incantations appeared in four forms: the prekante de ojo malo (incantation against the evil eye), the prekante de chefalo (incantation against mental anguish), the prekante de pelo (incantation against engorged breasts), and the prekante de kulivreta, (incantation of the serpent), used against blisters, danger, and anguish.

While the Capelouto women did not explicitly mention such incantations in their letters, the fears and anxieties they expressed about the evil eye, mental stress and danger, and breastfeeding were clearly those of many generations of Ottoman Sepharadi women that came before them.

Indeed, while Estreya emphasized her concern over Jack’s unemployment, she was equally concerned about the family’s mental health. Like Mathilda, Estreya emphasized Rachel’s responsibility as a nursing mother to protect her daughter from the family’s stress. In the process, she tasked both her son-in-law and her daughter with heavy burdens: in Jack’s case, Estreya insisted that he continue to search for employment in order to spare his family further financial hardship. What she asked of Rachel was less concrete, but equally weighty: Rachel’s job, as Estreya explained it, was not to “think too much,” presumably about her family’s troubles, so as not to allow her milk to “go bad” and harm the baby in her care.

Letter from Estreya (dictated to Lenora) to Rachel about Estreya’s granddaughter, Salva (ST01030-05, courtesy Al Shemarya).

Salva Shemarya

Salva Shemarya, whom Estreya and Mathilda fretted about in their letters to Rachel and Jack in the 1920s and 1930s, was born on September 16, 1922 in Portland, Oregon. Abraham and Estreya first learned of the birth of their granddaughter by mail. Jack originally wrote to his in-laws in early October to announce the news, but the letter was lost. His second letter finally reached Salva’s anxious grandparents in Rhodes on November 27, 1922. It was in this way that, worlds apart, Abraham and Estreya came to know their granddaughter through letters, first from her parents, and eventually from Salva herself.

Indeed, by 1933, when Salva was ten years old, her letters to her family back in Rhodes earned her the praise of her grandmother Estreya, who wrote:

I resivimos la letra de la kerida Salvutcha i la meldi i todo ya lo pude entender. Porke la de la otra ves no se pudo nada entender…a ti kerida Salva te rogo ke a la mama la entiendas porke sos la novya grande. I sienpre eskrivemos. I te aplikas bien para ke entendemos la letra.

“And we received the letter of dear Salvutcha [diminutive nickname for Salva] and I read it and I could understand everything. Because in the previous letter, one could understand nothing…I beg you to listen to Mother, because you are the big girl. And always write to us. And work on [your writing] well, so we can understand your letter.”

Having never learned to write herself, Estreya’s pride at her granddaughter’s achievements is palpable. Her letter, which she dictated to her daughter Leonora, went on to lament the slow international mail system, to recall the bunuelos (Sepharadi-style donuts) Rachel, her daughter, always made for Purim, and to wonder about her son-in-law Jack’s employment and everyone’s health. She also informed Rachel that her sister Bohora’s family faced financial troubles in Rhodes, too, before sending well wishes from extended family members.

Even as she celebrated her granddaughter’s current and future education, Estreya longed for her daughter Rachel’s presence around the holidays, she explained. The letter thus had a bittersweet tone, moving, as it did, between the joyful admonitions of a proud grandmother and the sorrowful recollections of a mother who missed her daughter. It ended with a similar level of ambivalence, passing along well wishes from the extended family while also interspersing them with descriptions of the financial troubles Estreya’s children were suffering both in Rhodes and in their new homes in Seattle.

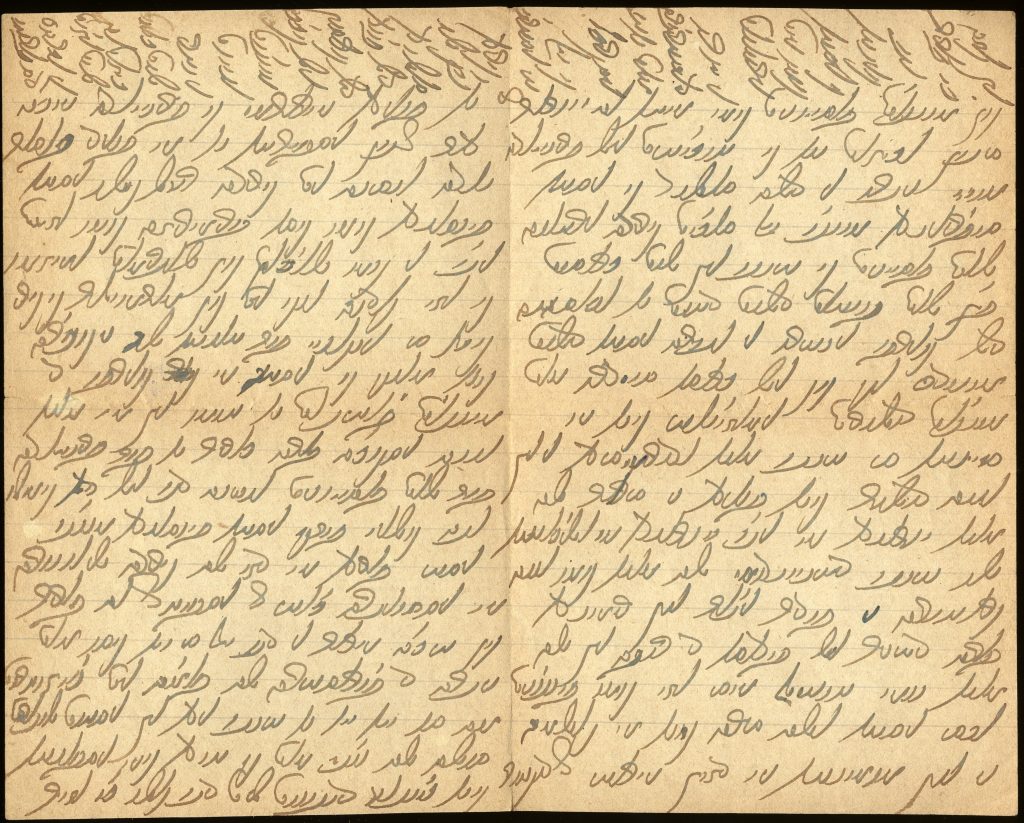

Letter from Miriam “Bohora” to Rachel. The quoted portion is in the top margin perpendicular to the main text (ST01030-12, courtesy Al Shemarya).

Miriam “Bohora” Capelouto Menashe

Miriam “Bohora” wrote to her sister, Rachel, on July 2, 1933 to report that her parents had recently traveled from Rhodes to Athens with their youngest sister Leonora so she could undergo medical treatment for an undisclosed illness. In this note, Bohora lamented the economic situation in both the United States and Rhodes and expressed her particular concern for Jack’s mental health as a result of his prolonged unemployment.

She concluded the letter on the paper’s margins, writing that, upon telling her mother-in-law of the “miseries” Rachel and her family were suffering in the United States, Bohora’s mother-in-law had responded that they were simply living “like everyone else over here” (le konti todas las estrechuras de la letra i disho eya ‘komo todos por aki’) — that is, in Rhodes.

Despite its otherwise pessimistic tone, Bohora concluded her letter by telling Rachel not to worry too much about her situation, and to remember to write. Her final words notwithstanding, there was clearly plenty to worry about: Bohora’s and her mother-in-law’s comments reveal the unrelenting instability of life both in Rhodes and Seattle in the 1920s and 1930s. Yet her letter, like those of the various women who sent their missives across the ocean to their loved ones during these years, also stands as a testament to Bohora’s commitment to trying to find hope even in dark times, and, above all else, to her family.

Bohora, Leonora, and their mother Estreya perished in Auschwitz after the remaining Jews of Rhodes were deported by German forces in July of 1944. Matilde lived and raised her family in Israel, while Victor returned to Rhodes in the 1960s where he lived until his death in 1973. Rachel lived with her family in the Pacific Northwest until her death in 1983 in Portland, Oregon. She was preceded in death by her husband, Jack, who died in 1960.

Rachel kept her family’s letters and passed them on to her son, Al Shemarya, who graciously shared them, along with his mother’s handwritten boreka recipe and other documents, with the University of Washington Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, thereby opening a window into the lives of the Shemarya and Capelouto women.

All translations and transliterations of postcards courtesy Izo Abram.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Mimi Brown is a Jewish Studies Master’s student in the Graduate Department of Religion at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Her current research focuses on the Ottoman immigrants who settled in the American south in the early twentieth century. She was a student in the UW’s summer Ladino Language and Culture course with Professor David Bunis.

Mimi Brown is a Jewish Studies Master’s student in the Graduate Department of Religion at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Her current research focuses on the Ottoman immigrants who settled in the American south in the early twentieth century. She was a student in the UW’s summer Ladino Language and Culture course with Professor David Bunis.