“Kome, es bueno: borekas para todos!” “Eat, it’s good: borekas for everyone” — Ladino phrase

If there’s one thing people know about Sephardic Jews, it’s borekas, those indulgent turnovers stuffed with cheese and potato or other types of gomo (filling; gomu as pronounced among the Rhodeslis) baked in dough ranging from fine phyllo to flaky yeast to pie crust. Known as börek in Turkish, the cuisine is part of a shared culinary tradition from the former Ottoman Empire, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean basin. Sephardic Jews enjoyed this and other savory pastries filled with a variety of vegetables known in Ladino as dezayuno (breakfast) and often eaten with guevos (en) haminados (brown hard boiled eggs).

Borekas from the Ladies Auxiliary of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth in Seattle

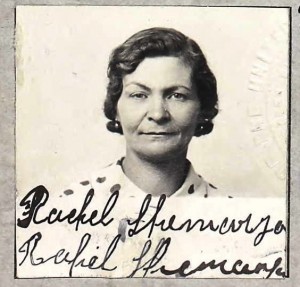

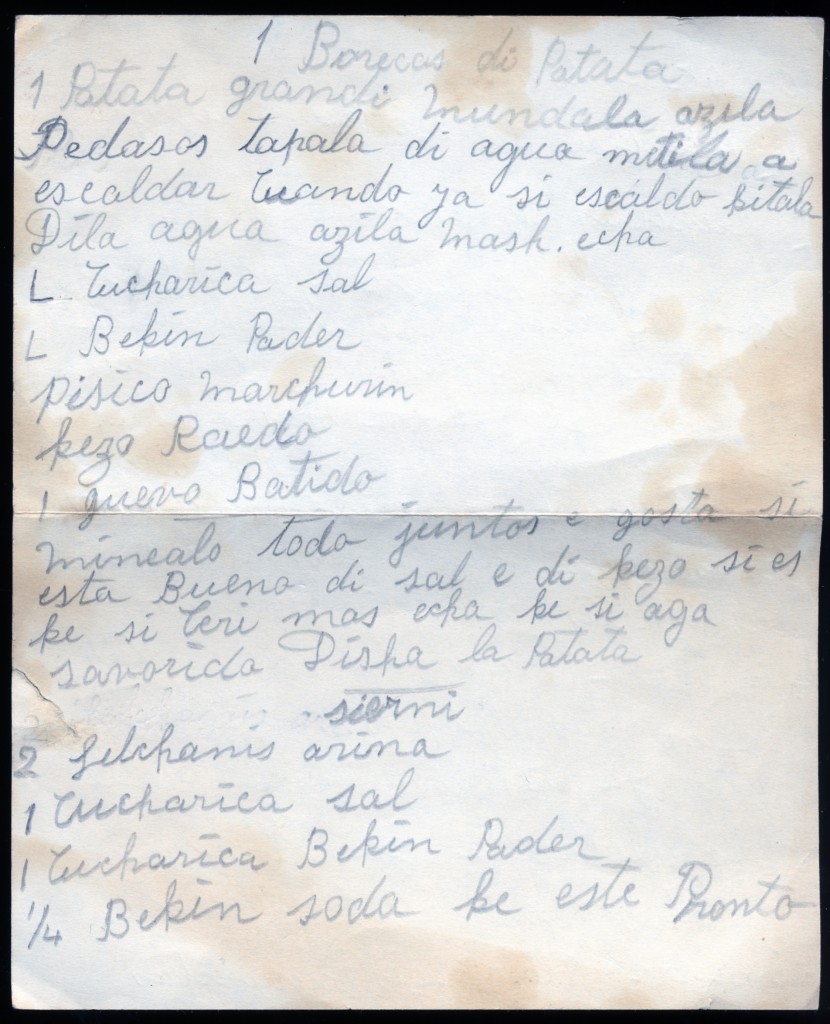

Every Sephardic cookbook includes a recipe for borekas, or burekas, but there is none quite like the one written down by Rachel (née Capelouto) Shemarya. A native of Rhodes, Rachel carried on the culinary traditions of her island here in the Pacific Northwest, where she recorded her own recipe for borecas di patata in her native Judeo-Spanish. For the first time, her Borecas di Patata recipe is available online at the Sephardic Studies Digital Library for all to try out for themselves. Her recipe is special not only because it is the only one in the Sephardic Studies Digital Library, but also because it offers a rare look into the lives of Sephardic women whose experiences often escape the written record.

From Rhodes to the Pacific Northwest

Born in Rhodes in August of 1898, while the island was still part of the Ottoman Empire, Rachel experienced the transition to Italian rule in 1912 and World War I before immigrating to New York in 1921. She eventually made her way to Seattle, where she married a fellow Rhodesli, Jack (Jacob) Shemarya, and raised four children.

As a child in Rhodes, Rachel attended the local Jewish school, the Talmud Torah, and in her teens she learned embroidery and French from the local nuns at an Italian Catholic school. Although Rachel spoke many languages (Judeo-Spanish, Turkish, Greek, Italian, French and English), her children recalled that she never learned to read or write well in English. But it was her musical and rhythmic voice, her folk cures and oral traditions, and her dramatic gestures, jumping up and down and acting out her stories, that made her well known and well liked in Portland and Seattle.

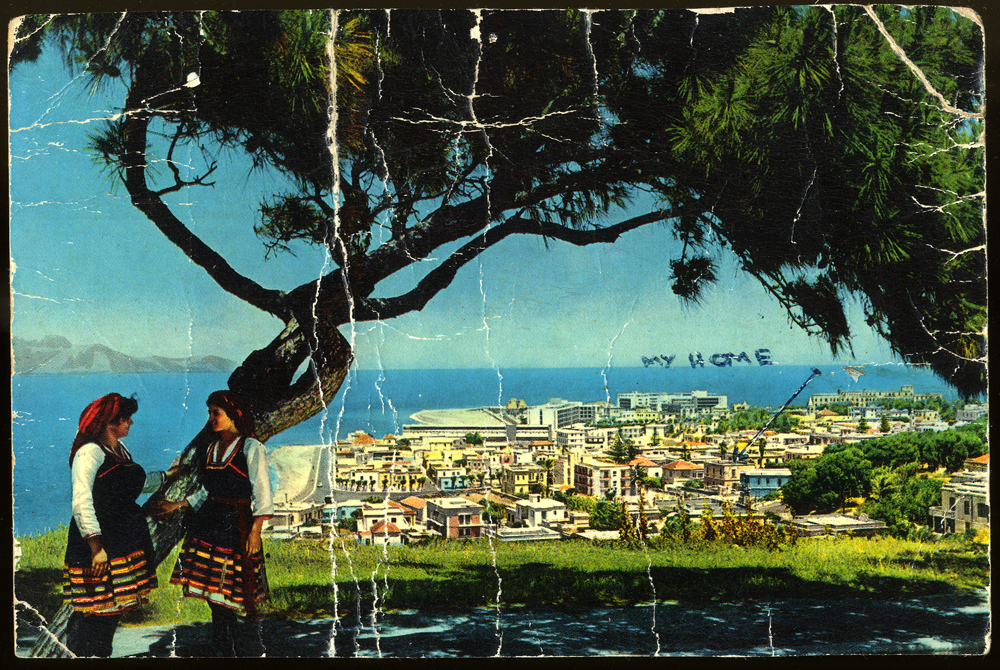

Postcard from Victor Capeluto to his sister Rachel Shemarya with an arrow pointing to their former home on the Island of Rhodes. Courtesy of Al Shemarya.

In an oral history, Rachel describes life on Rhodes in vivid detail. Her childhood was spent with her siblings and mother who waited for their father, an itinerant merchant, to return home about every six months for the Jewish holidays.

Her memories are filled with stories of Turkish baths and local Greek dances, where she practiced the mazurka, the lancier and the waltz–a sign of European influence on the island. She also remembers sitting outside in the courtyard of the synagogue with her friends playing paretha (parida, or “giving birth”), stuffing pillows under her clothes and pretending to give birth. She and her friends thus acted out the traditional expectations for them once they reached maturity as women.

In her account of folk beliefs and practices transmitted from the old world to the new, Rachel relates how to “make spantu,” to cure a person from shock by placing them in isolation. She also describes the relationship between the “upper” and “lower” worlds; tales of spirits of little people with fiddles that attempt to take unsuspecting individuals to the underworld; people who turn into cats; and demons who needed to borrow her uncle’s house for a wedding. The family moved in with a neighbor for a week, returning to find the place trashed with blood on the floor, though apparently the demons never bothered the Capeloutos again.

Recipe Saved

As for many Sephardic women of her generation, cooking played a central role for Rachel and shaped the life of her family and community. In fact, the creation and sustenance of both of the Sephardic congregations in Seattle, Ezra Bessaroth and Sephardic Bikur Holim, has been made possible due to the dedication of Sephardic women, who, for a century, have gathered together to gently pinch and flute perfect edges of their borekas, which are then sold at bazaars held as fundraisers by each of the congregations. These women brought their recipes from the former Ottoman Empire–Rhodes and Turkey–to America and transmitted the art of baking the way they themselves had learned: by dutifully observing the techniques of other women. Still today, there is competition over whose borekas are the best.

“She did not have a recipe book,” recalled Rachel’s daughter, Sylvia. “It was all in her head. It’s amazing! In fact she can’t look at a recipe and follow it very well today, if it’s printed. If somebody tells her how to do it, she’ll write it down in her own way. I learned by asking her, and by watching her.”

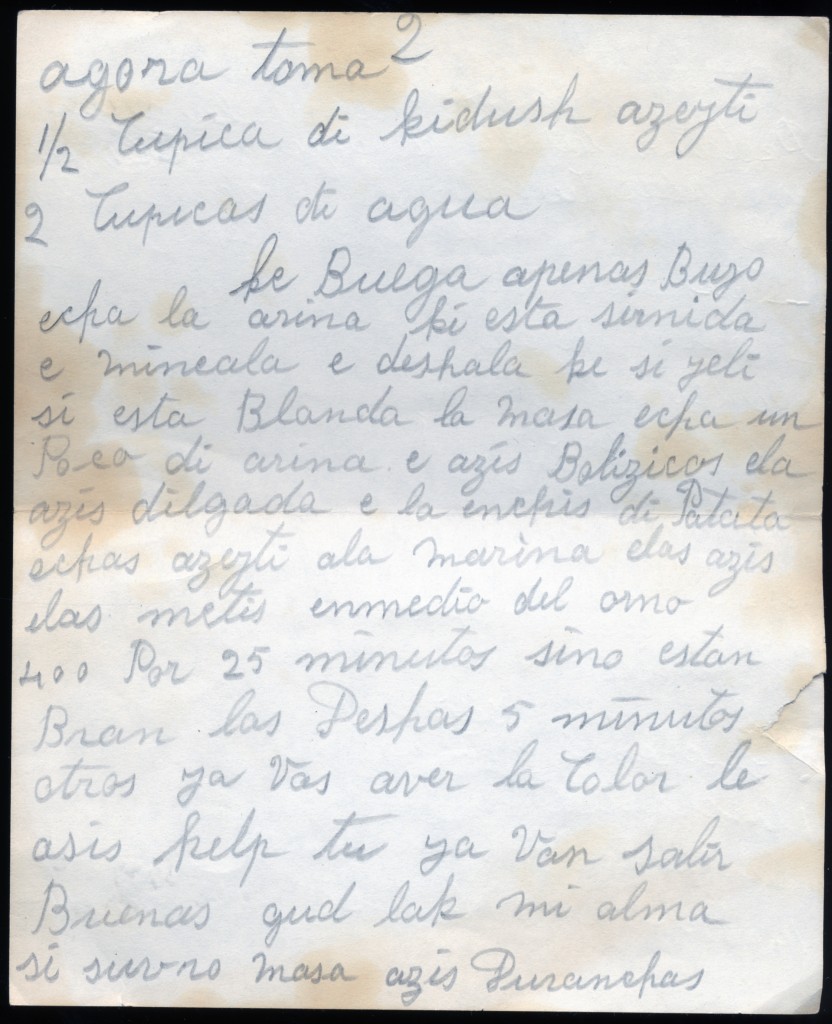

Donated by Rachel’s son, Al Shemarya, the boreka recipe is handwritten in Judeo-Spanish in Latin letters that also incorporates phonetically-spelled American terms, such as the ingredient, bekin soda. It is one of the most precious items from the Rachel Shemarya collection, which includes correspondence from relatives who remained in Rhodes as the increasingly dark cloud of the Second World War approached.

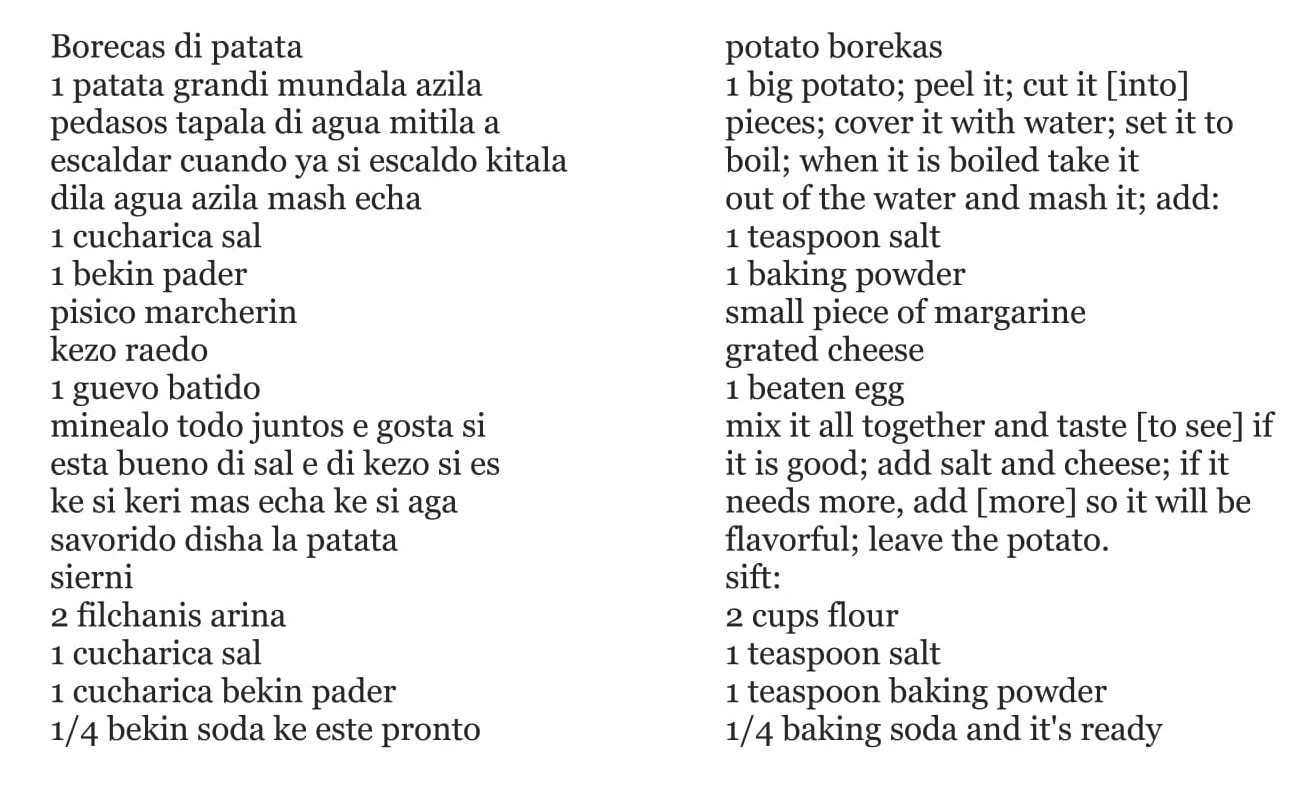

The second page of Rachel Shemarya’s Borecas di Patata

Transcription and translation of the second page of the recipe:

The language that Rachel used to record her recipe deeply reflects her cultural background and the specificities of the Rhodes dialect of Judeo-Spanish. It indicates that she could write in Judeo-Spanish and knew the Latin alphabet, evidence of her French education; in fact, she would have been among the first generations of Ottoman-born Jewish women to receive such a European-style education, usually at Alliance Israélite Schools. One of the identifying features of Judeo-Spanish from Rhodes is the tendency to engage in a phenomenon that linguists refer to as “vowel raising.” This means that instead of saying borekas de patata, as someone from Istanbul might say, those from Rhodes would say di patata.

Also note that the recipe cannot fully be followed without the help of its author or someone else “in the know.” What does the reference to “half a kiddush cup

Most illusory is the seemingly simple phrase: elas azis (“make them”). But, once the little balls of dough have been flattened and filled with potato, how to actually “make” them into borekas? How to fold the dough, pinch the edges, and actually create the borekas? What is the technique to be employed? Those details remain shrouded in mystery and accomplished, one presumes, only by recalling from memory or observation the precise way to form and shape the borekas .

The absence of specifics shows us that the recipe was not intended for the general public or for those completely unfamiliar with the dish. The recipe was indeed addressed to someone specific, to mi alma, “my dear.” The family recalls that “my dear” was one of Rachel’s sons, Jerry. The significance is therefore even more noteworthy for the recipe not only represents the recording of the culinary tradition into the written record, but also its transfer from the traditionally female domain to one in which men could also participate. Our publication of the recipe further signifies its entrance into the digital public sphere.

Paradise Lost

In the background of Rachel’s warm recollections of her native island and the recipe for a staple cuisine that she sought to transmit to future generations lie painful memories of a family murdered in the Nazi death camp of Auschwitz together with the other 1,600 Jews of Rhodes. The Sephardic Studies Program has digitized numerous letters sent to Rachel from family members who remained on the Island of Rhodes.

Dating from 1921 to 1933, the letters were handwritten in Ladino using the Sephardic cursive Hebrew script known as soletreo. Rachel’s mother dictated letters to Rachel’s sisters, a likely indication that her mother was illiterate. They begin with joy and congratulations to Rachel and Jack on the birth of their daughter Salva (Sylvia). But the last letters end with Rachel’s sister Leonora worrying that she will never get married (1933) and that she and their father are ill. In the depths of the Great Depression, her older brother Bohor could not find a job. She wrote: “El Dyo ke le avra puertas de piadad i ke no se menie de su repozo.” (May God open the doors of mercy for him and may he not lose his calm.)

While Rachel was busy attending to her family in the Pacific Northwest, her mother Estraya (nee Menashe) Capelouto, her younger sister Leonara, and her older sister Miriam were deported along with Rachel’s brother-in-law and her two nieces and four nephews. Their only remaining sister Mathilda (nee Capelouto) Rouso made her way to British Mandate Palestine and raised her family in the land of Israel. Their only brother Victor Capelouto survived the war by immigrating to the Belgian Congo. During the mid 1960’s he returned to Rhodes, now empty of this once thriving Jewish community. Victor never married and did not leave any children; he passed away on the island of his birth in 1973.

Photograph from Rachel Shemarya’s Petition for Naturalization, November 1941, courtesy of Ancestry.com

While Jewish Rhodes was irrevocably lost due to the destruction of the Holocaust, a taste of that world has been preserved in Rachel’s handwritten recipe. Rachel’s decision to write down her recipe symbolizes that the traditional way of transmitting the knowledge of how to cook and bake—by watching and learning—was becoming attenuated. By writing down her recipe, Rachel could instruct those who could not learn from her firsthand how to prepare her borekas—including you and me. Through taste, we may begin to understand the lives of Sephardic Jewish women like Rachel Shemarya and the traditions they saved for us to savor here and now.

We are grateful to her son Albert “Abraham iju de Rashel i Yaakov” Shemarya not only for his contribution of Ladino documents but also for his active support to the Sephardic Studies Program where he has presented and sang at all three International Ladino Day Events at the University of Washington.

The translation of this boreka recipe was provided by Rachel’s son Al Shemarya and edited by PhD Student Molly FitzMorris at the University of Washington’s Linguistic Department. Ms. FitzMorris is undertaking an in-depth study of the Rhodes dialect of Ladino and the phenomenon of vowel raising.

Many of the quotes and details about Rachel Shemarya were based on interviews by Felice Moskowitz with grandmother Rachel Shemarya, and her parents Sylvia Moskowitz and Edward Moskowitz, which she included in her college paper “Jewish Traditions, Beliefs & Interpretations Of Law,” May 12, 1971.

Additional thanks to Dr. Izo Abram, a researcher for our Sephardic Studies program based in Paris, who has kindly translated and transliterated all the soletreo letters in the Rachel Shemarya collection.

Please contact Ty Alhadeff if you have other recipes handwritten in Ladino that you’d be willing to share!

Excellent job Ty!

So very interesting!! Thank you so much for sharing…

Thank you Ty for your post. It brought many memories of my mother and her baking. My mother was born Rachel (neé Namer) Palombo, and my father’s (Isaac Palombo) mother was Fortuneé (Capelouto) Palombo. Seems like a small world.

Well… at least there is a recipe with more or less clear instructions. My grandmother’s recipe for burekas was “put some flour, a little salt, lot’s of oil, etc…” My sister and I have tried to replicate her recipes for burekas, shamali, trabados, boyos and more… and we haven’t been very successful

It was surprising for me that I could understand this recipe. I am portuguese and have been investigating about the roots of our modern day food (in Portugal). I have come to the conclusion that many things that we eat have been originated in jews food. But this legacy goes beyond the Iberian Peninsula. That is truly amazing! It is not only Jewish people that eat Sephardic food.

I remember the name Moswowitz from my Aunt Rosella & uncle Manny.

Wonderful article, Ty. Keep them coming!

I am dying of laughter. I translated what she wrote. It is spelled with her accent. ha ha. write me if you want to know more from me. vi.biernn@gmail.com

Thank you Ty

It’s wonderful to remember the atmosphere of the Jewish-Greek household. I am happy that the culinary tradition of borekas making is on this site. My father is from Thessaloniki . His sister used to bake all this delicious borekas and by seeing the recipes here I suddenly could smell the kitchen of my aunt.

Thank you for the wonderful account of making borekas aka burekas…

I learned to make borekas from my grandmother and aunt. I collect Sephardic recipes when I can find them. Also learned how to make Fideo from the same aunt. Delicious!

The rounded half moon pastries in the photo look more like “bouicos” than “bourekas”, which are a flakier pastry and triangular in shape.

This was so fascinating. Of particular interest that resonated with me were similarities with how I, too, learned to cook my grandmothers Sephardic recipes by watching and tasting..then trying to re-create after my grandmother passed…especially in the absence of recipes, but with only a note here and there that my grandmother had dictated to others on the abstract, vague “how-tos.”

My family also comes from Rhodes. I am a Capelouto. I had a great aunt Rachel too and my grandfather Alexandre had a first cousin, Victor Capelouto but he did marry and had children. Obviously we are a different branch of Capeloutos and we ended in in Turkey where our name became Kapeluto. From the Congo, now we are in Canada.

This is a wonderful article! My grandmother, Rebecca Elnékavé, whose ancestors lived in Toledo, Spain, made “Borrequitas.” I imagine these are quite similar. The iconic, elastic dough, made with boiling water mixed with oil, is Sephardic (no butter, or solid shortening) and is healthier than today’s pastry recipes. The meat sauce, with cumin, mint, cinnamon, and sometimes piñons (pine cone seeds) is distinctive and delicious. I fold them with a pinch and fold motion that ends up looking like a twisted rope around the edges, handed down over generations, in either “suns” (two rounds sealed together) or “moons” (one round folded over and twisted on the curved side). Happy to share recipes and techniques with anyone who is interested.

Thank you so so much for explaining all so well …. my grandmother my nona Eleonora Soriano made exactly the same way those lovely bourikitas…. I continue making them the same way and I hope my children will continue with this recipe, thank you ♥️