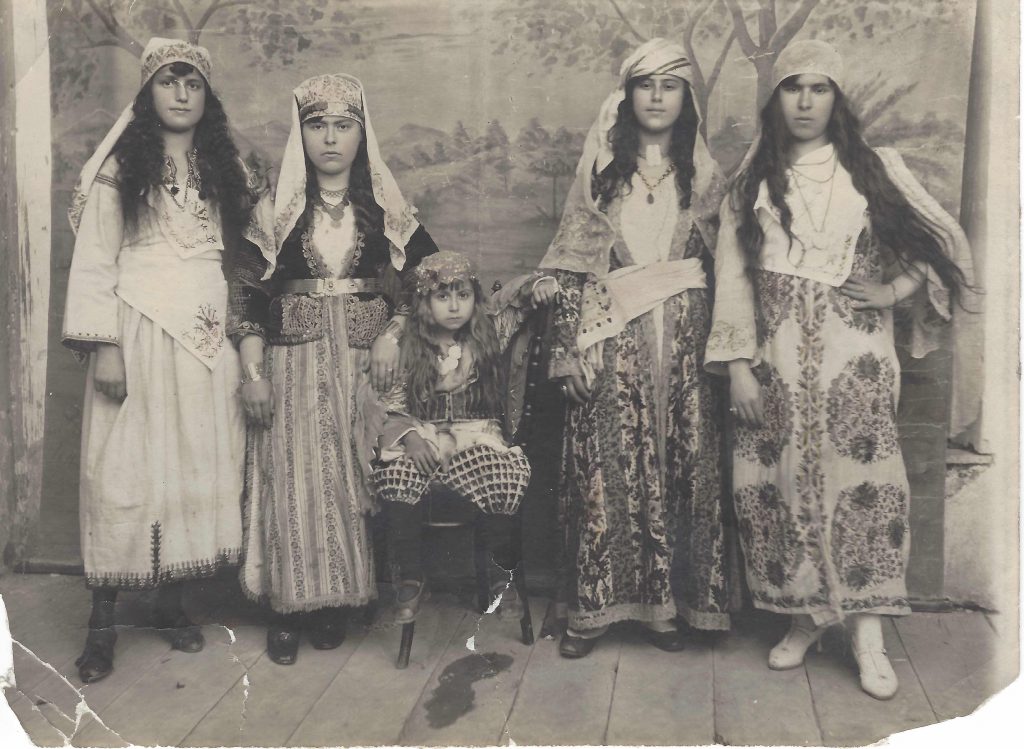

Capeluto family dressed for Purim on the Island of Rhodes. L to R: Unknown; Tamar Capeluto (daughter of Tamar “Behora” Capeluto and David Capeluto); Vida Capeluto (daughter of Tamar “Behora” Capeluto and David Capeluto); unknown; Esther Capeluto (daughter of Mussani and Rachel Capeluto), ca. 1930. Contributed by Cynthia Flash Hemphill.

By Makena Mezistrano

A popular adage reflects the revelry, joy, and even chaos that embodies the Jewish holiday of Purim: “On Purim,” it proclaims, “everything is permitted.” When it comes to donning Purim costumes — a custom which likely began in fifteenth century Italy and was inspired by Lenten carnivals — the laissez-faire attitude of the holiday enables one to temporarily conceal, emphasize, or alter elements of his or her identity that society may ordinarily discourage.

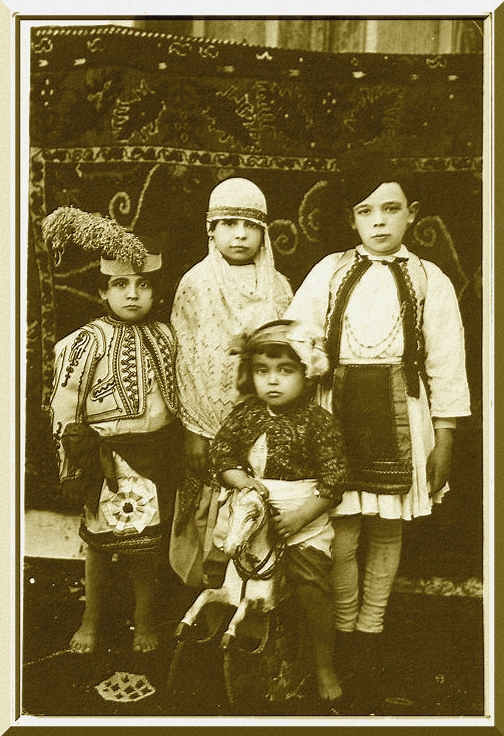

Portrait of Avram Nessim Levy, his wife (name unknown), and son (name unknown), ca. 1934. Captured after the family’s immigration to Palestine from Salonica. Contributed by Esther Tisas.

A recent call for photographs taken before 1960 advertised on our Sephardic Studies social media accounts culminated in the acquisition of ten new photos for the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, nearly all of which depict Sepharadim in some manner of special Purim dress. Captured on the Island of Rhodes, in Mexico City, in Salonica, and beyond, some of the costumes worn in these primarily posed portraits bear a striking similarity: They are clearly inspired by, or at least a reference to, Ottoman garb, whether taken before or after the collapse of the empire.

That these outfits were worn on Purim as costumes indicates that they were perhaps special, out of the ordinary, and rarely worn on an average day. What does it mean, then, when Jews living in presently Ottoman cities, later erstwhile Ottoman cities, chose to don Ottoman clothing as a costume?

While an exact answer may elude us, we can briefly consider how sartorial choices — and even mandates — developed throughout the empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the late nineteenth century, the Ottoman state was growing increasingly concerned with how its subjects represented the empire with their clothing. The most well known instance of a clothing item taking on political significance was the 1829 regulation for Ottoman men — regardless of religious communal affiliation –to wear the fez. At the same time, however, European fashion was encroaching on Ottoman borders, offering the prospect of identifying with and participating in fast moving cultural trends taking place beyond the empire.

Rebecca Notrica Buenos in costume during Purim on the Island of Rhodes, 1931. Before the Holocaust struck Rhodes, Rebecca emigrated to Israel; her sister, Rachel, and their parents, Isaac Notrica and Sarina Benatar, perished in Auschwitz. Contributed by Neil Sheff.

Caught between simply mimicking European style, as some critics warned against, and crafting their own Ottoman (or even “Oriental”) identity, men and women alike were hounded by state officials, journalists, and their peers for their fashion choices. In a moment at which one’s choice of head covering alone could indicate political affinity, showcase cultural competence, or underscore national belonging, Ottoman denizens — Jews included — became adept at what scholar Julia Phillips Cohen has called “clothes-switching, or the act of moving between differently styled outfits.” Moving between the perceived cultural boundaries of alaturka (the Ottoman Empire) and alafranka (Europe) also extended beyond clothes to home décor, food, language, dance and music, and even time.

As individuals navigated which occasions called for chapeo o fez (as one Ladino journalist framed the issue), and for which context a suit or an entari (the traditional Ottoman robe) would be preferable, a fascinating phenomenon arose: Cohen describes that by the late nineteenth century, many Jews reserved their Ottoman garb for Shabbat and Jewish festivals. The fez, for its part, morphed from an exclusively political symbol into something far more ambiguous, as it functioned as a convenient head covering during religious rituals when Jewish (and Muslim) men were required to cover their heads. Well after the empire’s collapse, Jews continued to wear their Ottoman outfits for religious occasions, then imbuing the clothes with nostalgia for a bygone world.

Emily Bardavid (b. Mar 12, 1902) in costume on the Island of Rhodes, ca. 1918. Courtesy Deborah Levy Hatherley.

And what of Purim costumes and their reference to Ottoman fashion, past or present? Before the collapse of the empire, a costume inspired by Ottoman clothes situated Purim among the other Jewish holidays that Jews rendered distinct — and within the realm of alaturka — by virtue of their sartorial choices. In the context of dressing up in costume, the wearers could be more experimental with elaborate headpieces, layered vests and jackets, and jewelry that they may not have worn on a “regular” Shabbat, even when they opted for alaturka styles.

For Jews living in a post-Ottoman world, perhaps we should return to the characterization of Purim as a day on which “everything is permitted.” In 1925, after the formation of the new Turkish Republic by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the fez was outlawed, viewed as a reminder of the bleak Ottoman past from which Atatürk wished to distance his new nation. Atatürk himself was also frequently photographed in European suits, and he demanded all Turkish citizens follow in kind.

Though some Jews continued to wear a fez whether they remained in Turkey or emigrated, Purim presented an opportunity in which even more Jews may have permitted themselves to embody their Ottoman past. For some, the customs may have even been a way to self-reference their more assured identity as Ottomans, whereas the status of Jews as full Turkish citizens was far less secure. As a holiday that was also widely photographed (whether because of the costumes themselves, or because Purim does not carry the same religious restrictions on work as other holidays), post-Ottoman Jews could memorialize and embody their past for posterity.

Thank you to all of our contributors for sharing your Purim photos with us. We wish everyone a Buen Purim!

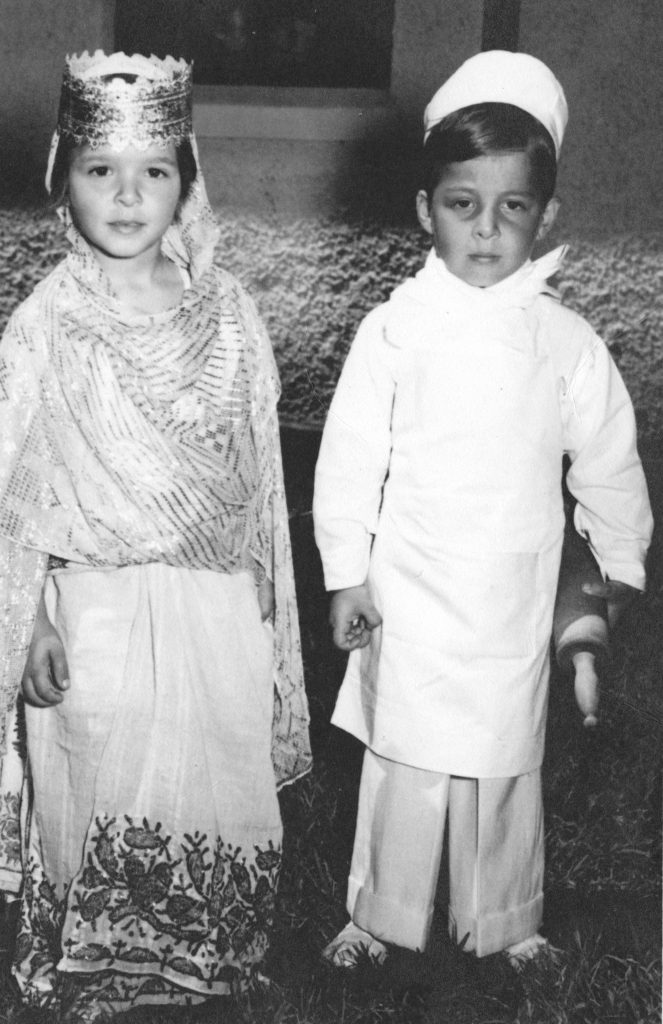

L to R, back row: Albert Israel, Isidore Capelouto, Emmy Capeluto. L to R, front row: Solly Israel, Alexandre Kapeluto, 1954/1955. Taken in Kinshasa (Léopoldville), Democratic Republic of Congo. Contributed by Sara Garnick.

Purim celebration in Mexico City with Jews from Damascus, Syria, 1935/1936. Sarina Sabin pictured in third row from the bottom at right. Contributed by her daughter, Lela Sabin Franco.

Young girl in Purim costume (name unknown) in Salonica, ca. 1950. Contributed by Sandra Adato.

Berro family dressed up for Purim on the Island of Rhodes. Pictured are Jaim, Matilde, Amelie, and Aslan Berro, ca. 1926. Contributed by Jaim’s son, Freddy Berro.

Erektil dysfunktion kan leda till att en man förlorar självförtroende och kan till och med leda till relationsproblem. Den njutning, den lycka som kommer från ett uppfyllande, tillfredsställande och underbart sexuellt förhållande är ojämförbar. Kamagra Oral jelly är ditt bästa alternativ xn--stenhrd-ixa.net/kamagra-oral-jelly/.

Two cousins prepare for a Purim celebration in the Sephardic community of Zimbabwe, mid-1950s. Contributed by Hannah S. Pressman.

amazing pictures xoxo…thank u 4posting them…

thank you very much, and happy purim!

Beautiful! My South American and Central American ancestors spoke Ladino well.

They immigrated to the new world in 1500-1700.

Such melodious language