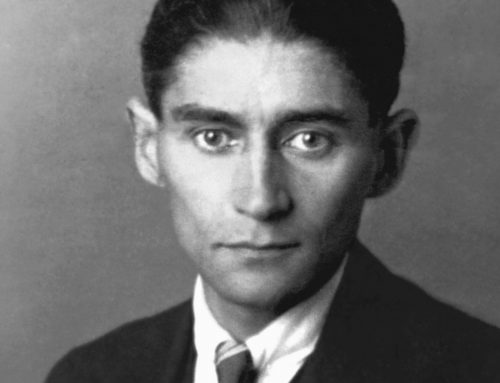

Yitzhak Löwy as a young man. Photo via the Embassy of the Czech Republic’s Franz Kafka exhibit.

Translation by Aaron Carpenter

I won’t mess around with figures and statistics in the following; I’ll leave that to the historians of Jewish theater. My goal is very simple: to submit a few pages of memories of the Jewish theater with its drama, its actors, its audiences, that I have seen, learned, and taken part in over ten years. Or to put it in another way: to raise the curtain and show the scars. Only after you recognize an illness can you find a cure and probably create the true Jewish Theater.

1.

For my pious, Chasidic parents in Warsaw the theater was of course trefe, nothing but chaser. There was theater only on Purim. Then Cousin Chaskel would stick a big, black beard over his small, blonde mustache, put his caftan on backwards and play a funny Jewish merchant – as a small child, I couldn’t take my eyes off him. Of all my cousins, he was my favorite. I couldn’t get his performance out of my head and, at barely eight years old, I acted like Cousin Chaskel in the cheder [primary school]. There was theater regularly in the cheder when the Rebbe [rabbi] was gone, I was the manager, director, in short everything, even the beatings that I got from the Rebbe were the biggest, but we weren’t bothered that the Rebbe beat us. Every day we thought up another play. And the year was a hope and a prayer: may Purim come, and I can see Cousin Chaskel dressed up again. I was certain that, when I was an adult, I would also dress up each Purim and sing and dance like Cousin Chaskel.

That you could dress up outside of Purim too and that there were many other artists like Cousin Chaskel, I had no idea though. Until one day I heard from Isruel Feldscher’s boy, that there is actual theater, where people perform and sing and dress up. Every night even, not just Purim. That there were theaters like that in Warsaw and that his father had taken him there a few times. This news completely electrified me – I was about ten years old at the time. A secret desire I had never suspected seized me. I counted the days that still had to pass, until I was an adult and could finally see the theater myself. At the time I didn’t even know that the theater was a forbidden and sinful affair.

Soon I learned that across from city hall was the “Grand Theater” [Polish: Teatr Wielki], the best, most beautiful in all Warsaw, even the whole world. From then on, the exterior view of the building positively dazzled me whenever I passed by there. One time though when I inquired at home when we would finally go to the Grand Theater, they yelled at me that Jewish children shouldn’t know anything about the theater, it isn’t allowed; the theater is just there for the goyim [non-Jews] and for the sinners. That answer was enough for me, I asked no more, but I had no more peace, and I was very afraid, that I would certainly commit this sin and would have to go to the theater when I was older.

When I went by the Grand Theater with two cousins one evening after Yom Kippur, there were many people on the theater terrace and I couldn’t look away from the “impure” theater, Cousin Meier asked me: “Do you want to be up there too?” I was silent. He probably didn’t like my silence and so he therefore: “Now, child, there isn’t one Jew there – heaven forbid! Not even the worst Jew goes to the theater the evening right after Yom Kippur.” All I took from that was that although no Jew goes to the theater after the end of the holy Yom Kippur, many Jews probably do go there on normal evenings throughout the year.

I went to the Grand Theater for the first time when I was fourteen years old. As little as I had learned of the official language, I could still read the posters, and there one day I read that The Huguenots[an opera by German-Jewish writer Giacomo Meyerbeer] would be played. We had talked about The Huguenots in the klaus [religious school], the play was by a Jew too, “Meier Beer” – and so I gave myself permission, I bought a ticket and that evening I went to the theater for the first time in my life.

What I saw and felt back then doesn’t belong here, just one thing: that I was convinced that they sang better than Cousin Cheskel and dressed themselves up much prettier than he. And I took another surprise with me: I had long known the ballet music from Huguenots, we sang the melodies in the klaus. Friday evenings when we sang Lechu Dojdi. And I couldn’t explain at the time how it was possible that in the Grand Theater they were playing what we had long been singing in the klaus.

From then on, I was a frequent guest at the opera. I just couldn’t forget to buy a collar and cuffs for each performance and throw them into the Vistula on the way home. My parents didn’t need to see such things; while I satiated myself on Wilhelm Tell and Aida, my parents were secure in the faith that I was sitting in the klaus looking at pages of the Talmud and studying the holy writings.

2.

A while afterwards, I learned that there was also a Jewish theater. As much as I wanted to go there, I didn’t dare, as it would be all too easy for someone to let my parents know. I often went to the opera at the Grand Theater and later also to the Polish dramatic theater. At the latter, I saw “Robbers” for the first time. It really surprised me that you put on such a beautiful play without singing and music – I would have never thought – and strangely I wasn’t angry with Franz, he made the greatest impression on me. I would have liked to have played him, not Karl.

Of all my classmates in the klaus, I was the only one who dared to go to the theater. But actually, we boys in the klaus had fed ourselves with all the “enlightened books.” I read Shakespeare, Schiller, Lord Byron for the first time back then. Of the Yiddish literature I could only get my hands on the great crime novels that America sent us in a language that was half German, half Yiddish.

A short time passed, I got no peace: a Jewish theater in Warsaw and I shouldn’t see it? And I risked it, put it all on the cards and I went to the Jewish theater.

I was totally converted. Even before the start of the play I felt totally different than with “them.” Above all no men in tuxedoes, no women in décolletage, no Polish, no Russian, just Jews of all kinds, women and girls dressed bourgeois in long and short dresses. And people talked loudly and unabashedly in their mother tongue. No one noticed me with my long kaftan, and I didn’t have to feel ashamed.

They performed a strange drama with song and dance in six acts and ten tableaus: Baal-Teshuve by Schumor. They didn’t start punctually at eight like in the Polish theater, but around ten and finished well after midnight. The lover of the …… and the intriguer spoke High German and I was amazed that I could immediately – without having a clue about the German language – understand such excellent German. Only the clown and the soubrette spoke Yiddish.

In general, I liked it better than the opera, the dramatic theater and the operetta put together, as first it was in Yiddish, German-Yiddish yes, but still Yiddish, a better, more beautiful Yiddish, and second everything was together here, drama, tragedy, song, comedy, dancing all together, life! I couldn’t sleep the whole night from excitement. My heart told me that one day I should serve the temple of Jewish art, that I should become a Jewish actor.

But the next afternoon, Father sent the children to the next room, he bid just Mother and me to stay. Instinctively, I sensed that a kasche was going to be cooked for me. Father no longer sat; he just kept walking up and down the room; with a hand on his small, black beard he spoke, not to me, but to Mother: “You should know, he’s getting worse day by day, yesterday, someone saw him in the Jewish theater.” Mother folded her hands, shocked. Father, completely pale, constantly walked up and down the room, my heart spasmed, I sat there like a condemned man. I couldn’t watch the pain of my loyal, pious parents. I can no longer remember what I said back then, I only know this, that after a few minutes of gloomy silence my father turned his big black eyes on me and said: “My child, remember, that will lead you far, very far away” – and he was right.

German original: The Kafka Project, Vom jüdischen Theater (I, 24)

Read Aaron Carpenter’s essay on Franz Kafka and Yiddish: “How Franz Kafka connected with Yiddish language and theater in Prague”

Aaron Carpenter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of German Studies at the University of Washington and is the 2022-2023 Pamela and Robert Center Fellow in Jewish Studies. His main areas of academic interest are minority literature in Austria and Germany, as well as literature from German minority groups in non-German-speaking regions, such as South Tyrol in Italy. His dissertation examines how writers from the former Yugoslavia and Austria use foreign words to name and discuss traumatic experiences. While his area of focus is on authors primarily from the former Yugoslavia, the theoretical basis for this work is grounded in the writing of German Jewish thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin. Before coming to the University of Washington, Aaron taught English in Qingdao, China, and Innsbruck, Austria, as well as working as a technical writer with Hewlett-Packard.

Aaron Carpenter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of German Studies at the University of Washington and is the 2022-2023 Pamela and Robert Center Fellow in Jewish Studies. His main areas of academic interest are minority literature in Austria and Germany, as well as literature from German minority groups in non-German-speaking regions, such as South Tyrol in Italy. His dissertation examines how writers from the former Yugoslavia and Austria use foreign words to name and discuss traumatic experiences. While his area of focus is on authors primarily from the former Yugoslavia, the theoretical basis for this work is grounded in the writing of German Jewish thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin. Before coming to the University of Washington, Aaron taught English in Qingdao, China, and Innsbruck, Austria, as well as working as a technical writer with Hewlett-Packard.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)