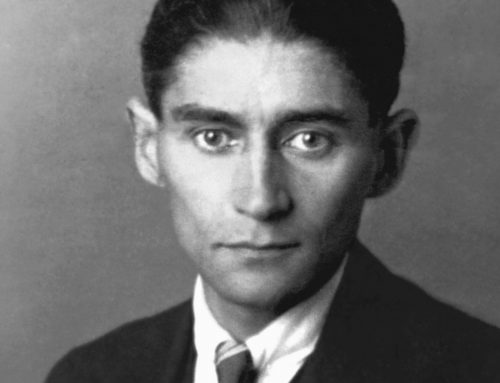

A metaphor for reading the Bible in translation: the cracks between the pieces hold meaning, too. Photo by Orin Zebest via Flickr.

By Hannah Pressman

It takes a persuasive writer to wring genuine psychological tension out of a grammatical discussion, but that is precisely what Aviya Kushner achieves throughout The Grammar of God: A Journey into the Words and Worlds of the Bible. A finalist for the National Jewish Book Award as well as the Sami Rohr Prize this year, Kushner’s book is that rare gift to readers: a scholarly examination of crucial matters in a field (in this case, biblical criticism and translation), combined with a soul-searching reflection on what it means to read, and to write.

“Should I read the opening of the world as a poem?” Kushner asks towards the beginning of her compelling memoir. Stuck in the space between Genesis 1:1 and Genesis 1:2, she finds herself in literary limbo: is the end of the Bible’s first verse meant to be understood as a period or as a poetic line ending? The King James Bible of 1611 open with these words:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep: and the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

Her curiosity piqued, Kushner samples various translations that either link or disconnect the creation story’s first two verses; some translate the verb bara as the past tense “created,” while others translate it as “creating.” After considering the different shades of meaning that result, Kushner concludes: “That lone dot determines how a reader might see the world: present, past, future.”

In other words, our understanding of the birth of the world can be fundamentally altered by punctuation.

Kushner’s orthodox Jewish family background granted her something rather unusual for an American: a truly native knowledge of Hebrew. For her, “Hebrew will always be my first language, the one I think in when I am tired, the one in which I first absorbed the Bible, the language of my dreams.”

In the book’s introduction she discusses, with breathtaking tenderness, “the context of family and home” that shaped how she understands the Bible. Kushner declares that as she wrote the book, her textual analysis had to be integrated with a narration of childhood memories: “I know of no other way to write this space between languages, and the layers of meaning in individual ancient words, than to include the people and places of my early life.” We hear about dinner table conversations that regularly included arguments about biblical grammar, and perhaps the most profound influence, her mother, a scholar of ancient Near Eastern languages who “had a life of the night” involving Akkadian tablets and piles of dictionaries.

Aviya Kushner. Photo via aviyakushner.com.

Kushner makes clear that her family was decidedly more “modern” than the Hasidim who resided on her block in Monsey, New York, yet the framework of that environment still posed limitations. As a result, she says, “I had to venture far from the house I grew up in for this project.” The journey landed her, among other places, at the University of Iowa’s famed writing program. Kushner documents the revelatory process of sitting in seminars with the novelist Marilynne Robinson and realizing that the English Bible her classmates knew was far different from the Hebrew version she had grown up hearing and loving.

The uncanny sense of alienation and wonder Kushner felt when confronted with English renderings of the Hebrew tanakh was the starting point for The Grammar of God. One of the deep pleasures of this book is accompanying Kushner as she finds the foreignness in a text that feels so familiar to so many. Her musings on translation open up productive new spaces to consider biblical idiom and how the body, “a battleground in translation,” does not always work in metaphors, particularly when representing the divine (as in the hard-to-translate phrase erech appayim, from Exodus 34:6). Some questions she poses are basic: why does the phrase “the Ten Commandments” not actually appear in the Bible? Other questions she poses are more existential: in the realm of the spiritual, in the domain of belief, who are we to say what is authentic and what is merely a pale imitation?

I am not sure there exists an accurate, easy genre name to classify The Grammar of God. It is in some ways a Künstlerroman, a classic tale of an artist’s development from a young age, tracing Kushner’s peregrinations to different parts of the world to pursue writing programs and teaching jobs. However, what this book is primarily concerned with is how we, as modern readers, can be empowered to swim in “the deep water of ancient Hebrew.” Aviya Kushner’s achievement in The Grammar of God is to show us the amazing interpretive stage that is established when we do the hard work in those spaces between: between different translations, between strange partners of a single metaphor, in the curious pause between two separate verses that may or may not be separated by a period.

This space between, is perhaps, where sacredness can ultimately be found. It is not a coincidence that Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator” includes the rather kabbalistic image of a broken vase. As he writes in 1923,

Fragments of a vessel which are to be glued together must match one another in the smallest details, although they need not be like one another. In the same way a translation, instead of resembling the meaning of the original, must lovingly and in detail incorporate the original’s mode of signification, thus making both the original and the translation recognizable as fragments of a greater language, just as fragments are part of a vessel.

A vessel that is glued back together includes the cracks between the pieces; any translation incorporates the decisions and tensions involved in the process of rendering a text foreign to itself. In The Grammar of God Kushner proves a sensitive reader who is keenly attuned to difference, and to the radical possibilities of reading that emerge when we trace not only the words, but also the cracks between the words.

This genre-defying book, in its combination of linguistic erudition and tender testimony, methodology and memory, deserves all the accolades it has received since being published last year. It now has a place on my bookshelf alongside H.N. Bialik’s Revealment and Concealment, Jacques Derrida’s Des Tours de Babel, and Naomi Seidman’s Faithful Renderings, classics in the field of Jewish language philosophy. While adding her unique voice to the discussion, Aviya Kushner’s The Grammar of God also serves as a necessary affirmation of what she herself suggests after probing Psalm 42: that “this is what it is to be human, to hope, to believe, to be a repeater of psalms and a singer of them.”

For full Flickr license and permissions via Creative Commons, see this link.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Thanks Hannah…