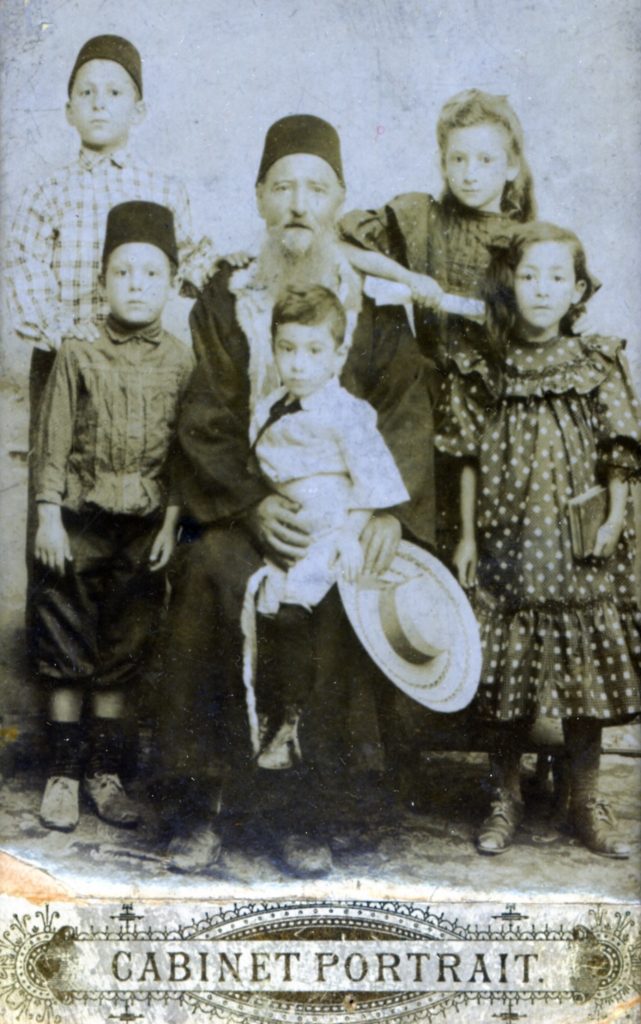

Morhaim family photo featuring Dona Morhaim Baruch, standing at right, ca. 1908. (Courtesy Isaac and Rachel Baruch via Ty Alhadeff, ST01382).

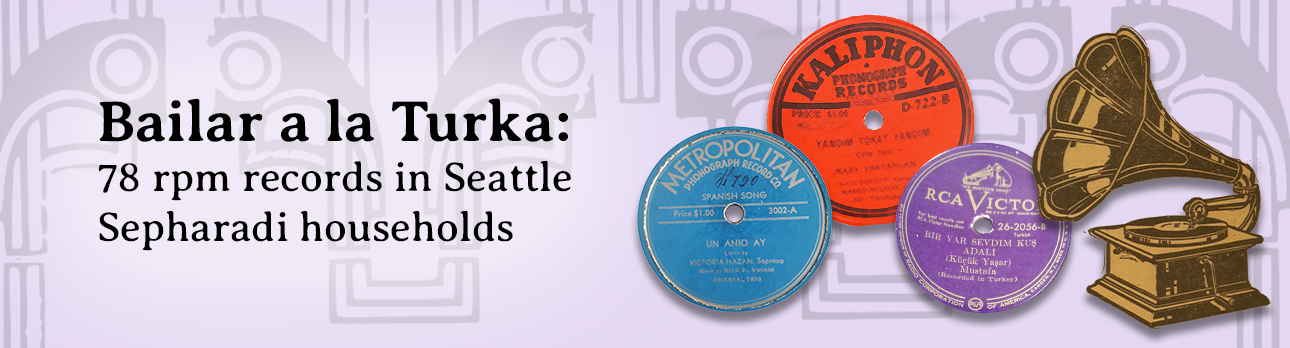

Bailar a la Turka: 78 rpm records in Seattle Sepharadi households

Exhibit Introduction

Azure blue, violet, fire engine red – bright colors on round labels. Emblazoned across the top, gold or silver letters – RCA Victor, Popular, Decca, Balkan, Kaliphon. Here and there, half covering the letters, a green or purple sticker – “The Balkan Phonograph Record Store, 42 Rivington St, NYC.” A ring of black shellac completes the platters.

These are the 78 rpm records in the collection of Sam “Sabetai” Hayman Baruch and his wife Dona Baruch (née Morhaim), Turkish Jewish immigrants from Marmara and Tekirdağ respectively and married at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth in 1921 in Seattle, Washington. Called taş plak (pronounced “tash plak”) in Turkish – literally “records made out of rock” – these discs represent a small chunk of a global recording industry that, from the very beginning of the twentieth century to the 1950s, manufactured and distributed records from around the world to international destinations including Seattle.

Let’s explore intriguing questions raised by the Baruchs’ record collection, focusing first on the local: Why did the couple purchase so few Ladino and so many Turkish language records? What did a phonograph culture look like in the living rooms of the interwar Seattle Sephardic community? And finally, widening our lens, how can a simple record label serve to broaden the story and significance of the Baruchs’ Turkish language records beyond Seattle and the borders of the United States?

Explore three themes

What are 78 rpm records?

Produced from shellac resin and other compounds (typically from South and East Asia), 78 rpm records spun with more revolutions per minute than 33 rpm records produced from vinyl after World War II, and, depending on their size (typically 10” or 12”), played from three to five minutes of recorded music. Colors of labels generally indicated a particular series or ethnolinguistic market for the discs. Amidst the lucrative recording industry across the first half of the twentieth century, the Baruchs’ collection offers a snapshot of one couple’s musical affections shaping and shaped by a lively global trade in records.

About the author: Maureen Jackson

Maureen Jackson, PhD, is singer, writer, and researcher. Her scholarship focuses on Ottoman and Turkish music history, in particular Jewish and multiethnic music-making, as a cultural lens for expanding our understanding of urban, socio-economic, and immigrant histories. She is the author of Mixing Musics: Turkish Jewry and the Urban Landscape of a Sacred Song (Stanford University Press, 2013), awarded the National Jewish Book Award in Sephardic Culture. Her research has received support from the Fulbright Foundation, NEH, and the Turkish Cultural Foundation, among other institutions. She has performed with the Seattle Turkish Music Ensemble; worked with the Art & Music Therapy program at Seattle Children’s Hospital; and authored a monthly column in Victory Music Review. Her current music research focuses on eastern Mediterranean music-making centered in late Ottoman Izmir, and ethnographic and archival projects in immigrant Turkish Jewish communities in the United States.

Maureen Jackson, PhD, is singer, writer, and researcher. Her scholarship focuses on Ottoman and Turkish music history, in particular Jewish and multiethnic music-making, as a cultural lens for expanding our understanding of urban, socio-economic, and immigrant histories. She is the author of Mixing Musics: Turkish Jewry and the Urban Landscape of a Sacred Song (Stanford University Press, 2013), awarded the National Jewish Book Award in Sephardic Culture. Her research has received support from the Fulbright Foundation, NEH, and the Turkish Cultural Foundation, among other institutions. She has performed with the Seattle Turkish Music Ensemble; worked with the Art & Music Therapy program at Seattle Children’s Hospital; and authored a monthly column in Victory Music Review. Her current music research focuses on eastern Mediterranean music-making centered in late Ottoman Izmir, and ethnographic and archival projects in immigrant Turkish Jewish communities in the United States.

The author is indebted to Isaac Azose, Ty Alhadeff, and other Seattle Sephardic community members for sharing their family histories; to readers Joel Bresler, Gabriel Skoog, Chris Silver, and Isaac Azose for their comments on this project; and to Makena Mezistrano for website design.