Dual Sides of Spain’s History with Jews

Ryan Gompertz at the UW History Department Convocation, June 2015.

Living in Barcelona, Spain, as a child was a transformative experience for Ryan Gompertz (UW Class of 2015). A native of Camas, a small town near Vancouver, Washington, Gompertz lived abroad with his family for five years while his father, an engineer, was on assignment for Hewlett-Packard. The experience did more than help him acquire excellent Spanish: he also gained an appreciation for Spain’s complex twentieth-century history, in particular the lingering legacy of General Francisco Franco’s violent regime.

Gompertz reflects, “I have a strong memory of walking in Barcelona and seeing a church wall riddled with bullet holes. I asked my mother what had happened, and she explained about the attacks on clergy that took place during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). The war still felt like recent history when we were living in Spain.”

At the same time, however, Gompertz found out that his own family’s story intersected with Spain’s history in a surprising way. His great-uncle Werner Cahn, a Dutch electrician, had escaped certain death by crossing the Pyrenees into Spain in 1943. Cahn was among roughly 40,000 Jewish refugees who avoided Nazi persecution by passing through Spain en route to eventual safety.

Naturally inquisitive, Gompertz was struck by these dissonant versions of Spanish attitudes to Jews. He explains, “My great-uncle insisted that his life had been saved by Spain, but I was curious about the real story behind Franco’s national government. There was an obvious discrepancy between the anti-Semitic rhetoric of Franco’s regime and the real fact that a significant number of Jews escaped through Spain during the war, due to the help (or at least helpful inaction) of local officials.”

He says, “I’ve always known a little bit about my family history, but I wanted to know more.”

The questions were all there. He just needed the right tools to answer them.

“A Quest of Discovery”

Several years after his life-changing experience in Barcelona, Gompertz began his studies at the University of Washington in 2011. He majored in Political Science and History with a minor in Law, Society, and Justice. His extracurricular involvement included membership in Sigma Chi Fraternity, where he was philanthropy chair, and several internships.

Gompertz took full advantage of academic opportunities to supplement his formative encounters with Spanish history. Prof. Glennys Young (Department of History and Jackson School of International Studies) offered a class on the Spanish Civil War that helped to fill in many blanks in his knowledge of the Franco dictatorship. Young, whose forthcoming book is entitled Refugee Worlds: The Spanish Civil War, Soviet Socialism, Franco’s Spain, and Memory Politics, observes: “In the junior seminar that he took with me in Fall 2013, Ryan demonstrated a real flair for historical analysis—for asking excellent questions and reading sources imaginatively. The Spanish Civil War captured his historical imagination. He wanted to learn as much as he could.”

Then, in Spring 2014, Gompertz took a history majors’ seminar with Prof. Devin Naar, chair of the UW Sephardic Studies Program and faculty for Jewish Studies and the Department of History. The course was HIST 498D From the Mediterranean to America: Jewish, Christian and Muslim Diasporas in the Twentieth Century. As is often the case, a push from a professor was all he needed; encouraged by Naar, Gompertz used his final paper as the chance to synthesize all of his questions in a rigorous way. The result was a twenty-page analysis entitled “Memories in the Pyrenees: Jewish Refugees and Spain During the Second World War.”

Lisa Fittko, photographed in 1939 for a passport.

Gompertz dug into the history of the period, looking at such works as Haim Avni’s Spain, the Jews, and Franco (1982). His fluency in Spanish helped him examine several primary sources from the Francoist regime. Yet he found the most compelling source material to be testimonies from Jewish survivors, such as Lisa Fittko’s Escape Through the Pyrenees. Fittko (1909-2005) was born in the Ukraine, became a political activist, and helped hundreds of refugees escape Nazi-occupied France during the war.

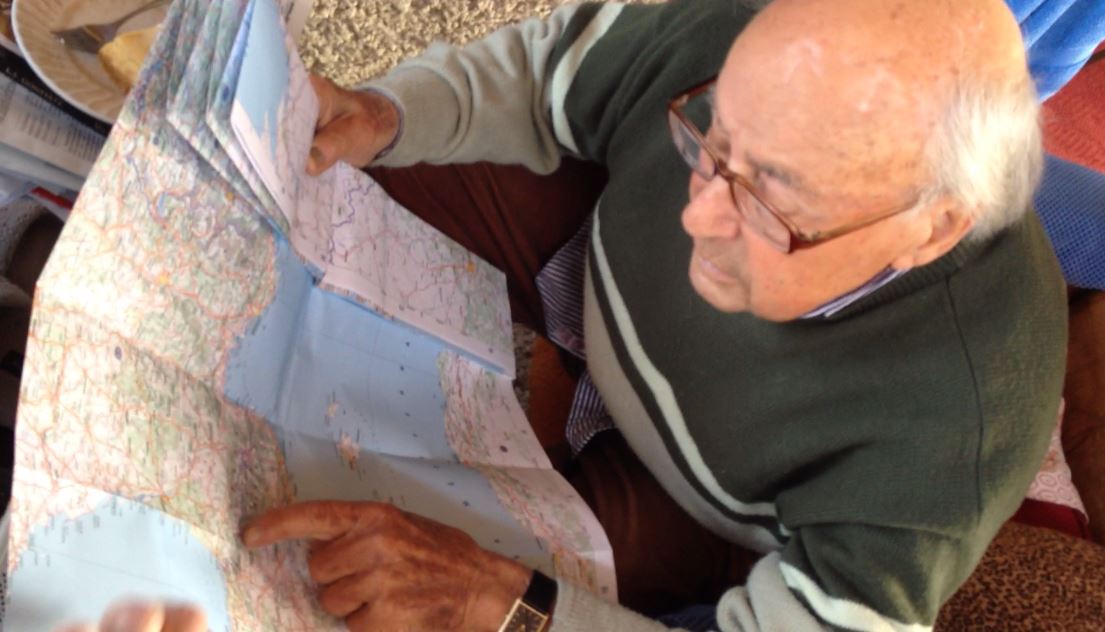

Far less famous, but also intricately connected to the project, was his own great-uncle Werner Cahn, who had been born in the Netherlands. Gompertz had the good fortune of being able to sit with Cahn at his home in San Diego and record him speaking, looking at maps, and explaining the story of his incredible wartime escape. Cahn made it out of Spain in 1944 and spent four years in Haifa, on Israel’s northern coast, before immigrating to America. Gompertz included excerpts from the interview with his great-uncle in his final paper for Prof. Naar.

The overall picture that emerged from his research was of a National government that was politically pragmatic as Franco tried to consolidate power in the years following the Spanish Civil War. Officially neutral during the Second World War, Spain had an ambiguous policy toward Jewish refugees and the covert rescue efforts happening along its borders.

Gompertz explains, “The Spanish government policy literally changed from month to month during the war. It created a vacuum at the bottom level, so local officials could interpret it however they wanted. Some individuals were legitimately sympathetic to the plight of the Jewish refugees; others were happy to accept bribes or turn a blind eye as Jews passed through the border; others refused to cooperate. Sometimes a refugee’s fate just depended on the day or which official he happened to talk to.” For this reason, in every personal narrative he read, the writer attributed his or her survival to incredible luck.

Prof. Naar’s guidance was crucial as Gompertz balanced the different accounts he was uncovering: “The biggest understanding I gained from Prof. Naar was how to interpret memoirs in the context of history. Everything is written through a perspective, and people’s perspectives are just as important as what actually happened. In my project I compared the personal narratives to the historical sources and compared how those two things coexist and complement each other, even when they sometimes contradict each other.”

Developing this kind of nuanced critical thinking is one of the clear benefits of Jewish Studies courses and studying the humanities in general. For Gompertz, honing his analytical skills paid off: this past spring he was accepted to UW School of Law.

The Mapping Memory Project

The homepage of Ryan Gompertz’s Mapping Memory project at jewishstudies.washington.edu, developed through a Digital Media Fellowship at the Stroum Center.

Most students file their seminar papers away or recycle them when the quarter is over. For Gompertz, though, the quest wasn’t over when his history seminar ended. It had just begun.

Gompertz turned to the Stroum Center to get help developing a digital project that would reflect his research on Jewish refugees in Spain. He decided to dedicate the summer before entering law school to expanding his paper into an interactive online exhibit called Mapping Memory. Working with Kara Schoonmaker, the Stroum Center’s Digital Media Coordinator, Gompertz developed a digital map tracing the escape routes of his great-uncle, Fittko, and other refugees. As a Digital Media Fellow, he also wrote two articles for jewishstudies.washington.edu and edited his great-uncle’s interview video into shorter segments.

Gompertz’s project is certainly timely, as the Spanish-Jewish relationship is now a major news headline: Spain recently passed legislation enabling Sephardic Jews to return and claim Spanish citizenship. This invitation, coming over five hundred years since the Spanish Inquisition and expulsion of Jews from the Iberian peninsula in 1492, has generated significant soul-searching and debate in the Sephardic community about what it would be mean reestablish the connection with the country that caused such a traumatic rupture. While Gompertz’s great-uncle Werner Cahn was not himself Sephardic, Cahn’s story, and that of other Jewish war refugees who fled to safety via Spanish back channels, can provide a broader perspective on how we view Spain’s treatment of Jews over time.

In addition, Prof. Naar, who also teaches a lecture course on Holocaust: History and Memory, points out, “Spain did intervene to protect a select number of Sephardic Jews from Salonica who, thanks to the Spanish protection they received, were deported by the Nazis not to Auschwitz but rather to Bergen-Belsen. From Bergen-Belsen, the Spanish government permitted these Sephardic Jews to be extradited to Spain but only if they had made arrangement to leave the country once they arrive. In other words, Franco may have been willing to help the descendants of those Jews his country had kicked out, but he was not willing to undo the expulsion decree of 1492.”

Werner Cahn retraces his path through Europe during a 2014 conversation with Ryan Gompertz, his great-nephew.

Beyond shedding light on Spanish Holocaust historiography, Gompertz—like many in his generation—is keenly aware that the voices of Holocaust survivors and war refugees are an increasingly precious resource. “My great-uncle is 94 now, so I felt it was very important to preserve his stories. I think every family has stories like this. I want to be sure that these stories don’t get forgotten.”

Even though his law studies will keep him busy, Gompertz hopes to continue the research he started in Prof. Naar’s course. “This was the most demanding project of my undergraduate career. And I still want to keep going. Next, I want to compare the situation in Spain with that of other ‘neutral’ countries. I would love to find more survivors and find out if their stories support my findings. And I would love to go back to Spain and find voices who can speak about the Franco side and attitudes to Jews, because even when they were helping Jews, the Jews were still the ‘others’ in Spain.”

Prof. Naar calls Gompertz “a standout student” and is enthusiastic about the potential for his online mapping project: “I am excited for Ryan to bring the story of his great-uncle, as a microcosm of the trajectories of Jews fleeing Nazi occupied Europe, to broader public attention. Ryan gets at some of the complexities involved in Spain’s policies towards Jews during this challenging period and helps us better understand the various ways in which those refugees who entered Spain have remembered their experiences.”

Ultimately, Gompertz hopes that his quest will simply encourage others to begin family history projects. “My goal is that someone will look at my project online and be inspired to go record one of their relatives telling the story of their life.”

Editor’s Note: A version of this article appeared in the Stroum Center’s Fall 2015 Newsletter.

Links for Further Exploration

- The Mapping Memory Project

- Mapping Memory: From Story to History, blog post by Ryan Gompertz

Ryan Gompertz’s exploration of Spain’s history with Jews is truly fascinating. His personal connection to the topic through his great-uncle Werner Cahn’s wartime escape adds depth to his research. I admire his determination to uncover the complex truths about Spain’s policies during the war and the contrasting experiences of Jewish refugees. It’s heartening to see him preserving his great-uncle’s stories and shedding light on a lesser-known aspect of history.

Moreover, his initiative to create the digital project “Mapping Memory” is commendable. By developing an interactive online exhibit and tracing the escape routes of refugees, he’s not only preserving history but also making it accessible to a wider audience. His dedication to sharing these narratives highlights the importance of remembering the past, especially the stories of those who might otherwise be forgotten.

I’m intrigued by his future plans to delve deeper into Spain’s relations with Jews during the war, comparing it with other neutral countries and seeking diverse perspectives. His passion for historical research and commitment to understanding complex historical events are truly inspiring. Best of luck to Ryan as he continues his academic journey, and kudos for his impactful work in preserving and sharing these vital stories.