The Textual Interplay of Scriptures

“Reading is no more than actualizing possibilities in one’s own mind, and projecting them upon the object named ‘text’.” —Mieke Bal, Anti-Covenant: Counter-Reading Women’s Lives in the Hebrew Bible (1989).

I am a student and scholar of the believers’ movement that emerged in the seventh century Hijaz and became the religion of Islam, and so the Hebrew Bible is an important text in my studies. That statement may strike many people as odd or startling, but it is true. To begin to understand the context and content of the Qur’an, you have to be conversant in the narrative of the Hebrew Bible, as well as the New Testament.

Characters such as Abraham, Moses, Aaron, Mary (sister of Moses and Aaron), Adam, Abel, Solomon, Noah… and the list goes on, appear in the Qur’an. Their stories are not retold so much as referenced. For example, a verse will start, “And remember when we made an appointment with Moses for forty nights,”

The interplay of the textuality of the Qur’an with Jewish and Christian scripture and legend is one of the things that I find most fascinating and educating about studying Islam. The believers’ movement, that would become Islam, emerged in a richly textured religious milieu. The traders and travelers from the Zoroastrian Sasanian Empire to the Northeast and the Christian Byzantine Empire to the Northwest mixed with the pagan religions of the Arabian Peninsula and the Jewish tribes who had been living there for hundreds of years. In seventh century Arabia, a new tradition was emerging that was influenced by these traditions, and which would influence their mutual development in the rich centuries to come.

A Mysterious Text about Zipporah

Who was Zipporah and why does her narrative matter?

Discovering this intermingling of textualities sent me back to the Hebrew Bible for a fresh look, and I found one particular passage that piqued my curiosity. As it turns out, it has piqued a lot of curiosity over the millennium. Nearly every scholar, from the authors of the Targums to the contemporary, has declared or alluded to the mysteriousness of Exodus 4:24-26, which I will call The Zipporah Pericope [technical term for a textual excerpt].

The exodus out of Egypt begins with a prequel journey. Moses, hero of the exodus, travels with his family from Midian, the place of his escape and the place of his marriage, with his wife, Zipporah, and his family back to the center of Egypt to demand freedom for the Israelites from Pharaoh.

“And it happened on the way, in the night-lodging,

that YHWH confronted him,

and he sought to kill him.

And Zipporah took flint

And she cut of the foreskin of her son,

And she caused it to touch his legs;

And she said:

“For a relative by bloodshed you are to me.”

And he let him go.

Then she said:

“A relative by bloodshed on account of circumcision.”[1]

On the way, in the night-lodging place, an interaction takes place between YHWH, Zipporah and her son, which is fraught with danger and potent symbols. On my first reading, I was struck by the agency of this mother, who acts out a visceral ritual to save the life of her son. I read that Zipporah’s son was endangered. She senses the danger and performs a ritual marriage, the blood on the boy’s genitals mirroring the virginal blood on a wedding night, and brings her son and herself into a formalized familial relationship with the deity who threatens him.

This reading has not been written or shared in formal circles before, but I cannot believe that other women, knowing what women know about marriage, the danger it evinces, and the power of its ritual to bring the participants into relationship with an extended family and their deity, have not read this pericope as I have. In the liminal spaces of life—from the womb into the world, from childhood into marriage—life and death hang in the balance, and what are rituals for if not to order the chaos? The ritualizing of danger, in this case bloodshed, transforms something dangerous into something pure, that is, into something sacred and controlled.[2]

The Covenant of Circumcision

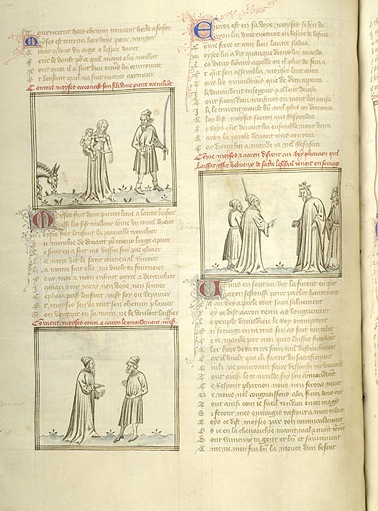

French illuminated manuscript from the 14th century depicts the life of Zipporah, Moses, and their son. From the Index of Christian Art at Princeton University.

Circumcision, as a Jewish ritual, has a long history. It has been institutionalized as a covenantal mark since the canonization of the scriptures at least. The choice of this particular ritual as the covenantal mark has been scrutinized, particularly when anthropologists realized that many non-Israelite peoples practiced circumcision, and varying arguments have been put forth. For example, circumcision is associated with fertility, as the covenant with Abraham was a promise to make him “exceedingly fruitful” (on this topic, see scholars from Philo to Eilberg-Schwartz). In medieval rabbinic contexts, the blood of the circumcision replaces the sacrificial blood of the firstborn. There are other covenants, of course, within the Torah (the covenant of the pieces [brit ben habetarim] in Lekh Lekha, Genesis 15:1-21 for example, or the covenant with Noah after the flood in Genesis 9:1-19), but none has been retained and maintained like circumcision.

I would like to note here that I am aware of some of the contemporary debate that is going on with regard to the ethics of circumcision. I am, at present, not addressing this debate directly. I am interested in exploring an alternative reading of text — one that utilizes a feminist narratology to consider experiences of the characters in this story—within a historical context. My experience of the scholarship to date on this passage is that gender is considered only as an ontological attribute, and in that case, only to distinguish the actors, one from the other.

The Lens of Gender

“If women today are better equipped than men to understand those parts and aspects of the Bible which have been under-emphasized, there is no reason for surprise, let alone for disturbance. Women, by virtue of their so far excluded position, can rearrange the text in such a way that the accounts of women’s lives as we find them in the Bible become more interesting, more instructive, more inspiring than they were read so far. Unfortunately, they also become more disturbing, due to the disturbing distribution of power in the text’s pre-text.” –Mieke Bal, Anti-Covenant: Counter-Reading Women’s Lives in the Hebrew Bible. (1989).

As a feminist scholar, excavating ancient texts, I do not expect to find an ideal past. Instead I search for uncomfortable passages, of the kind that startle the reader. Scholar Mieke Bal uses an evocative metaphor for passages such as the Zipporah Pericope, a “wandering rock,” which she describes as the “glacial tilts that traveled with the ice toward a new and alien world where they were put to a use foreign to their origin.”

Exodus 4:24-26 is one of those “wandering rocks.”’ It is a strange and perhaps “foreign” passage that survived in the canon—one that invites inquiry, and readings that are outside of the tradition. It is also a passage with disturbing implications. My reading of circumcision as a ritual with anthropological links to marriage and gender relations is certainly not an easy one. If, as I imagine, the male infant is brought into relationship with God just after birth, the question begs to be answered, when and how is the Jewish female brought into relationship with God? The answer that suggests itself is through marriage. The “disturbing distribution of power” that this implies is not easy for many readers, today or at any time.

This is a question that I bring up only to acknowledge yet another difficulty in scriptural scholarship. The implications of this question are for the reader to answer for herself; the answers being informed by her tradition and/or faith.

Questions of Agency

The kinds of questions that I can try to answer, both in my reading of the Hebrew Bible and in my reading of the Qur’an, are the questions of narratology:

1) Who speaks? Who has the right, the power, to give the account?

2) Who sees? Whose view is given in the account?

3) Who acts? Which agents perform which acts, and what is their position as agents?

In the Zipporah Pericope, one of the most strikingly unique aspects is one that is not often taken up by scholars, ancient or modern: that is Zipporah’s agency. To take note of this fact is to acknowledge the traditionalism that inhabits the sphere of the scholar – traditionalist readings note Zipporah’s gender as a problem to be explained, rather than seeing the passage as an opportunity to explore. But, there is much to be explored. She acts in a capacity that is everywhere else in the Hebrew Bible reserved for men, and she speaks. To whom is Zipporah speaking? Traditional readings would have Zipporah speaking to an Angel of God, to Moses or to her son, but, like Hagar, another foreign wife of a patriarch, I believe that she speaks to God.

There are obvious reasons why this text was a problem for the traditional reader, and their problem has been inherited, consciously or not, by the modern scholar. Yet there is no reason why such a reading should not be considered valid, even if uncomfortable. My hope is that by reconsidering the multiplicity of readings and counter-readings of this strange Exodus text, which go beyond a traditionalist view, a more nuanced perspective will emerge—one that more fully reflects the experience of all the characters present in the text, even if they appear for only a moment.

[1] Exodus 4:24-26 Translation by the author with the assistance of Dr. Gary Martin, 2014 [2] Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger; an Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (New York: Praeger, 1966). Summer Satushek is the 2014-15 Mickey Sreebny Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. She is an MA candidate in the Jackson School Department of Comparative Religion. Summer is engaged in textual analysis of the Qur’an that takes into consideration the complex interreligious and intercultural conversations of the seventh-century Hijazi milieu. Her research project is tracing articulations of gender, both ontological and constructed, from the Torah, the Qur’an, and the Hadith Qudsi. This project combines research on the changing meaning of circumcision and its relationship to ideas of marriage, purity and religious identity with research on gendered language in the Qur’an. Through the intersections of the two tracks, she hopes to explore the mutual influence of conceptualizations of divinely ordered hierarchy and balance in the Judeo-Islamic context.

Summer Satushek is the 2014-15 Mickey Sreebny Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. She is an MA candidate in the Jackson School Department of Comparative Religion. Summer is engaged in textual analysis of the Qur’an that takes into consideration the complex interreligious and intercultural conversations of the seventh-century Hijazi milieu. Her research project is tracing articulations of gender, both ontological and constructed, from the Torah, the Qur’an, and the Hadith Qudsi. This project combines research on the changing meaning of circumcision and its relationship to ideas of marriage, purity and religious identity with research on gendered language in the Qur’an. Through the intersections of the two tracks, she hopes to explore the mutual influence of conceptualizations of divinely ordered hierarchy and balance in the Judeo-Islamic context.

Leave A Comment