Indiana University, Bloomington. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Adam Rovner

I knocked on the dark wood of Professor Stephen (Shmuel) Katz’s solid office door in 1998 as a comparative literature doctoral student newly arrived to Indiana University in Bloomington. My hair was long and carefully unkempt. I wore shorts and a t-shirt and was sweating in the soupy August humidity. Inwardly, I was cursing ever having left the Middle East for the Middle West. There was no שוק [market] in Bloomington. There was barely any חומוס [hummus], let alone קומפלט [“komplet”]. I had returned to the US less than a year before, after having spent several years in Israel.

Available in Israel but not in Indiana: קומפלט (“komplet” hummus). Photo by Ma Blogeria food blog.

There I had volunteered on a religious kibbutz while flirting with observance and with בנות משק [kibbutz girls], but לילות לבנים [all-nighters] with the latter prevented me from getting to שחרית [morning prayers] on time for the former. Then I moved to Jerusalem and was an אולפן [ulpan] drop-out. Instead, I worked in an upscale Italian restaurant and amassed an esoteric food vocabulary (חמצוצים [sorrel], anyone?) and command of grammar rules no native speakers observed: רוטב שמנת ופטריות, hold the דגש קל (sadly, this is untranslatable).

I later perfected my slang during military service (sometimes I still get that שביזות יום א’ [“Sunday blues”]). And I completed a master’s degree in comparative literature at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where I learned to casually pepper my conversation with words like חידלון [cessation]. More importantly, my professors there managed to get me to stop saying כאילו [“like”] every third word.

Now I was back in the U.S.A. and ready to put my various and haphazard registers of Hebrew to use. Professor Katz invited me into his office, a warren of bookshelves that hemmed him in behind a desk that was littered with papers and folders and piled with old cloth-bound Hebrew books. The air conditioner sputtered beneath drawn shades. Florescent lighting gave the dimness a greenish hue. I sat down on a chair that seemed designed to totter. The scene made me nostalgic for Hebrew University, where nothing was engineered for comfort.

Katz and I spoke in Hebrew: his was correct, mannered, slightly old-fashioned. My Hebrew was informal and contemporary; in short, קלוקלת [imperfect]. I still don’t know what, besides his natural generosity, induced Katz to donate his time to undertake that first of many directed readings courses with me. But read we did.

We read H. N. Bialik. We read Uri Zvi Greenberg. We read Abba Kovner. We even read some American Hebraists, the subject of my essay in What We Talk about When We Talk about Hebrew (edited by Naomi B. Sokoloff and Nancy E. Berg; published in 2018 by UW Press) and of Katz’s most recent book, Red, Black, and Jew. Mostly we read S. Y. Agnon, Katz’s first love and about whom he has published two books. I had done a lot of reading in Hebrew during my M.A., but I hadn’t touched Agnon because his reputation for difficulty was too intimidating.

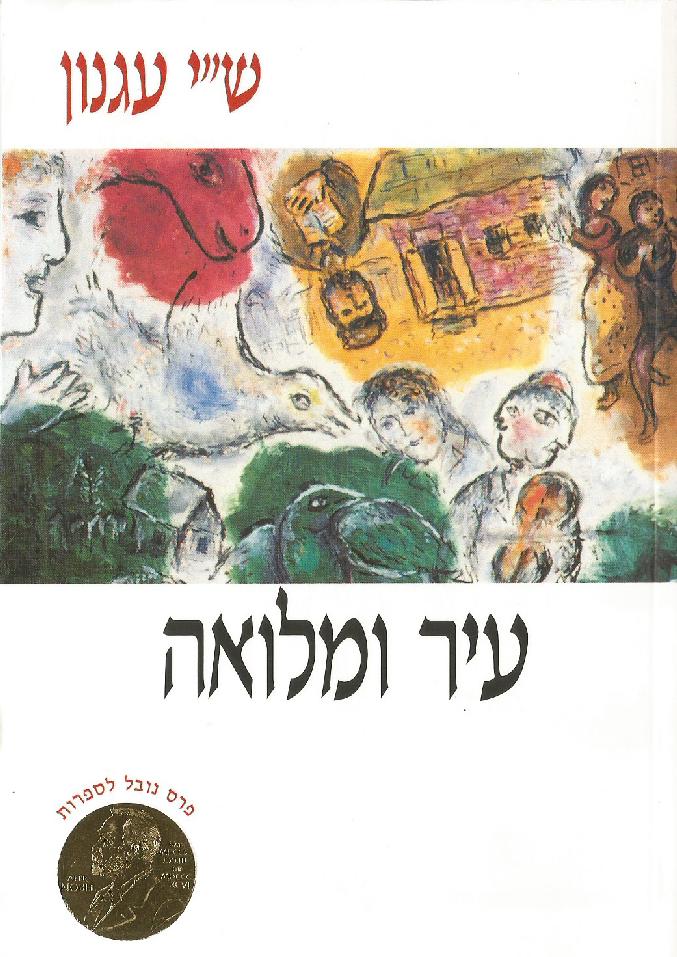

S. Y. Agnon’s short story collection עיר ומלואה (“Ir Umeloah,” A City in Its Fullness), collecting Agnon’s stories about his hometown, Buczacz, located in present-day Ukraine

At first, I stumbled over archaic vocabulary such as: רפיון , יי”ש, לגין [weakness, schnapps, jug]. But thanks to Katz’s encouragement, I soon realized I had an advantage that many native speakers of Hebrew lacked. Though my formal religious background was spotty—I left ישיבה [yeshiva] after second grade—I knew the liturgy, the language of ritual and observance, and had studied תנ”ך [tanakh] at a rudimentary level. The paperbacks of Agnon that I read often contained footnotes glossing elements of Jewish tradition or textuality that I knew from my home, or from my adopted homes in Israel.

I quickly warmed to Agnon’s rich vocabulary and slyly subversive styles, and I savored each new Hebrew expression. Words I would never use in my daily life somehow penetrated my subconscious. One morning I woke up and told my (mostly) Israeli wife: “I dreamt I was in Jerusalem and asked a guy if he was a חנווני [grocer], and he made fun of me.” Agnon might have liked how his Hebrew-speaking version of Buczacz seeped into my Indiana dreams of Zion. As a student, it wasn’t always easy to keep up with the intense reading schedule Katz set for me, which might explain why my nighttime brain was moonlighting with Agnon. I didn’t always enjoy it, but I learned and I grew, as I hope my own students will.

Agnon is not one of my specialties, but I love to read and teach his work, and I find that his prose still snakes its way into both my sleeping and my waking moments. Agnon wrote: כל חידוש אמיתי קשור בלשון [“every real innovation is one of language”]. I believe that my studies with Stephen did indeed enrich my Hebrew and my life. For that, I am happy to thank מורי שמואל כץ [“my teacher, Shmuel Katz”] and I dedicate my essay in What We Talk about When We Talk about Hebrew to him.

Adam Rovner contributed a chapter about Hebrew and the community to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (UW Press 2018), edited by Naomi Sokoloff and Nancy Berg. He also participated in our series of short essays on Hebrew & the Humanities and moderated a conversation between authors Dara Horn and Ilan Stavans on the past, present, and future of the Hebrew language.

Adam Rovner (Associate Professor of English and Jewish Literature, University of Denver) is the author of In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands before Israel (NYU Press, 2014) and of essays on modern Jewish literature that have appeared in academic journals such as Partial Answers and AJS Review. He has served as Translations Editor for the magazine Zeek, handling the publication of Hebrew texts in English.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)