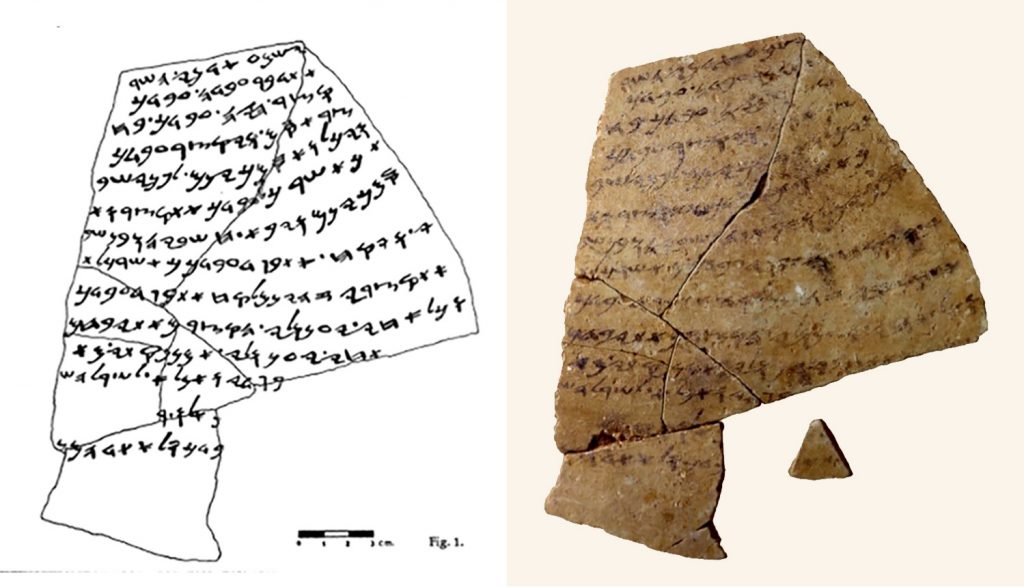

On the left: a drawing of an ostracon (pottery shard with writing on it) from Joseph Naveh’s 1960 article in the Israel Exploration Journal. On the right: a photo of this ostracon, via the Center for Online Judaic Studies.

By Corinna Nichols

A special excitement greets the discovery of archaeological finds related to the Bible.

In the past year alone, archaeologists have found enigmatic water ducts near Jerusalem, perhaps related to the production of linen for the Israelites’ ancient Temple; Roman swords stashed in a cave near the Dead Sea that may be connected to the Bar Kokhba revolt by Jews against the Romans in 132 CE; and a 24-room farmhouse from around 700 BCE in the Israeli city of Rosh HaAyin whose substantial grain silo illuminates the importance of grain in the ancient diet.

Even if you aren’t an academic, if you know the Bible, you might connect these findings with familiar elements of the biblical world, such as the linen worn by the priests of the Temple, or the grain harvest in the story of Ruth.

For scholars in my field, biblical studies, the ability to assess artifacts’ authenticity is crucial for preserving the integrity of historical narratives around religious texts. This is doubly hard to do, because the Bible’s cultural importance makes counterfeiting a lucrative trade. (Recently confirmed or suspected forgeries include supposed fragments from the Dead Sea scrolls and the James Ossuary, an ancient container of bones that purportedly belonged to Jesus’ brother.) Thus, a genuine artifact from the biblical world is a treasure.

What is an ostracon? Notes, letters and receipts from biblical times

Excavation site at Yavne Yam (“Yavne on the Sea”), south of Tel Aviv. Via Wikimedia Commons.

In this essay, the ancient letter I will share is known as the Yavne Yam ostracon, named after the beautiful coastal site near which it was found, Yavne on the Sea, about 13 miles south of Tel Aviv. (The letter is also sometimes called the “Mezad Hashavyahu ostracon” after the name of the site where it was excavated, a fort about a mile from Yavne Yam.)

An ostracon is a piece of broken pottery, commonly used in the ancient world for writing letters, receipts, and notes — the ancient equivalent of scrap paper.

This letter was written in the 7th century BCE, in the time of King Josiah of Judah, one of the few kings the Bible judged as doing “right in the eyes of the Lord.” Even the testy prophet Jeremiah says that King Josiah “upheld the cause of the poor and needy” (Jeremiah 22:16) — while berating Josiah’s son for failing to live up to his father’s standard.

An ancient harvester seeks justice

The letter is from a harvester, who was working at a village near Yavne Yam, Chatsar-Asam. Based on the practiced handwriting, it is likely that a scribe wrote down the letter for him. The name of the harvester himself doesn’t survive, nor does the name of the “governor” (a local official) he writes to.

He begins by respectfully referring to himself as the governor’s “servant”:

May my lord, the governor, hear the word of his servant.

He then narrates his tale, explaining that he had harvested and finished all his work for the day.

As for your servant, your servant was harvesting in Chatsar-Asam. And your servant harvested and measured and stored as usual before the Sabbath/quitting time.

But then:

When your servant had measured his harvest and stored it as always, Hoshayahu, son of Shobai, came and took the cloak of your servant. It was when I had finished my harvest as always, he took the cloak of your servant!

He adds that he has witnesses to this and, finally, asks for the governor’s help:

And all my fellow-workers will answer for me, those harvesting with me in the heat of the sun. My fellow-workers will answer for me, “it’s true!” and I am innocent from guilt and free from my obligation.

The lower part of the ostracon is broken, so the text has gaps and breaks off at the end, but it seems to end with another plea for justice:

… my cloak so that I will be made whole/redressed. It is for the governor to return … servant. And grant to him mercy … your servant and do not leave me confounded.

Why a stolen cloak mattered — and why the Bible specifically protects clothing

If you are a reader of the Bible, the taking of the cloak as payment (or insurance for repayment) may sound familiar:

If you do take the garment of your neighbor as surety, you must return it to him by the time the sun goes down, for it is his only covering — it is his garment for his body. What else can he sleep in? And when he cries out to Me, I will hear, for I am gracious. (Exodus 22:26-27)

The same injunction is also referenced in Deuteronomy 24:10-13, 24:17, Amos 2:8, and Job 22:6. The idea of taking a cloak is akin to the modern idea of taking “the shirt off my back” — one’s last possession.

Ancient cloth rarely survives in the Levant, the region of the Middle East where ancient Judah was located, but we do have a rare cache of examples from Timnah, in present-day Israel.

Ancient cloth excavated from Timnah. Photo by Clara Amit, via the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Looking at the even fibers and tight weave of the remaining scraps brings home what a slow and painstaking process cloth-making is. A large garment like a cloak would represent a great deal of labor and would be a valued possession.

But what Hoshayahu, son of Shobai, (our villain) does goes beyond taking a covering. Recent biblical scholarship on clothing, for example Laura Quick’s “Dress, Adornment, and the Body in the Hebrew Bible,” suggests that clothing was a part of the ancient idea of “self,” just as much as the body and the spirit. This attitude is reflected in verses such as Job 29:14: “I put on righteousness, and it clothed me; my justice was like a robe and a diadem.” So Hoshayahu potentially took a part of the harvester’s self along with his cloak.

How this letter illuminates the biblical world it came from

This letter offers valuable insights into its world. First, it shows that the biblical laws and words of the prophets about taking clothing from the poor were addressing a real problem. While we cannot know that the harvester knew of the Bible, the Bible knew of him, or rather of his situation.

We should appreciate the structures that lie behind this letter’s existence. For example, the harvester must have had some confidence that he could go to someone in authority without reprisal, and that they would right a wrong. And he is confident that this wrong will be recognized as such.

This points to a period of order in society. King Josiah, who “upheld the cause of the poor and needy,” the accessible governor, the willing scribe, and the potential witnesses all had roles in making justice possible for the harvester.

We, in turn, can make these deductions securely because of the care and integrity of modern archaeologists and scholars, publishers, and preservationists, in bringing this ostracon to light.

Perhaps, then, another message of this letter is that a just society arises not only from the law, but is woven into the fabric of the world through the countless everyday actions of those who uphold its principles.

Corinna Nichols is a Ph.D. candidate in the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Interdisciplinary Program. Her field of study is the Hebrew Bible and ancient Middle East. Corinna worked for twenty-five years in the tech field, including roles at IBM, Lenovo, and Amazon, before falling in love with ancient Israel. She has a B.A. in Latin from Wellesley College, a B.S. in Computer Science from American Sentinel University, and an M.A. in Near Eastern Languages and Civilization from UW. She is the coauthor of two published papers on the Hebrew Bible.

Corinna Nichols is a Ph.D. candidate in the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Interdisciplinary Program. Her field of study is the Hebrew Bible and ancient Middle East. Corinna worked for twenty-five years in the tech field, including roles at IBM, Lenovo, and Amazon, before falling in love with ancient Israel. She has a B.A. in Latin from Wellesley College, a B.S. in Computer Science from American Sentinel University, and an M.A. in Near Eastern Languages and Civilization from UW. She is the coauthor of two published papers on the Hebrew Bible.

Leave A Comment