The modern-day port of Haifa, which received a large amount of capital from the Palestine Economic Corporation. The PEC was founded in the early 1920s by American Jews. Photo by Zvi Roger. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Jacob Beckert

The new Israeli government, sworn in on December 29th, 2022, is widely considered to be the most right-wing government in Israel’s history. While opinion polls suggest Israelis don’t support many of the pillars of the new government, including anti-LGBTQ laws, decreased support for religious pluralism, and harsher policies towards Palestinians in the West Bank, it is the American Jewish community that appears to be most disturbed by this dramatic turn of events.

In response to the numerous expressions of concern by American Jewish organizations, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has tried to alleviate American Jewish concerns, promising to rein in members of his coalition. However, alongside Netanyahu’s more conciliatory message, a growing chorus of right-wing Israeli politicians is advocating for a different approach to American Jewish concerns: ignore them.

While no one disagrees that implementing the most extreme policies of the far right in Israel could lead to a historic rupture between the American Jewish and Israeli communities, some on the Israeli far right believe American Jewish support provides little of material value to Israel, and not much would be lost if American Jews relationship to Israel was fundamentally altered.

While this view is partially rooted in the current political landscape (such as the belief that evangelical Americans hold more important political sway than American Jews), it is also a recapitulation of a long-standing stream of Zionist thought that American Jews haven’t “pulled their weight” in supporting the Zionist movement and the State of Israel.

The myth of American Jewish indifference

In its earliest days in the 19th century, Zionism was primarily a European movement. Jewish persecution in Europe and the constant presence of “the Jewish Question” — the question of whether Jews could ever truly be part of European nation states — led some Jews in Europe to see Jewish nationalism and a return to Palestine as the best option for global Jewish survival.

The significantly more violent nature of European antisemitism meant that most refugees to Palestine in the 19th and early 20th centuries came from Europe, not the U.S., where Jews felt far more secure. Yet some American Jews were involved in the Zionist movement from its earliest days.

Beginning with the onset of World War I, which devastated and fragmented European Jewish communities, American Jews became a much larger presence among the Zionist leadership, as well as the most significant financial contributors to supporting Jewish life in Palestine.

Poster from the Zionist Organization of America soliciting donations, 1919. Via the Library of Congress.

Yet, despite American Jews’ contributions, a common belief arose among Zionists that American Jews weren’t doing enough to contribute to the cause, or weren’t contributing to Zionism in the right ways.

Chaim Weizmann, the longtime head of the World Zionist Organization and later the first president of Israel, constantly complained that American Jews’ financial contributions were insufficient, and one of his chief deputies, Menachem Ussishkin even quipped that American Jews had Gentile heads while Eastern Europeans had Jewish hearts.

David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, was equally scathing, repeatedly stressing that American Jews’ true role in Zionism was to move to Israel, despite the importance of financial and political aid from American Jews for the nascent country.

These ideas reflect a larger undercurrent in Zionist thought that began in the earliest days of Zionism, and continues to this day: a belief that outside of the small percentage of Jews who move to Israel, American Jews offer little benefit to Israel or the Zionist movement.

A new perspective: The history of the Palestine Economic Corporation

For years historians have thought that there was some truth in this critique of American Jews’ support for Israel. While the reasons for the low immigration numbers of American Jews to Palestine were clear, a number of historians accepted the notion that that prior to World War II, American Jews offered financial aid to Palestine that was not commensurate with the wealth of the community.

This argument was supported by the fact that the Zionist Organization of America consistently failed to reach ambitious fundraising goals. The problem with this assumption is that official Zionist organizations, such as the Zionist Organization of America, only represent a small portion of the overall financial support offered by American Jews to Palestine.

My research of largely unexamined financial and company records housed at the New York Public Library’s rare books and manuscripts division reveal that between 1926 and 1939, more significant aid for Palestine was offered through a different channel: private investment, most notably through the Palestine Economic Corporation (PEC), a for-profit organization run by American Jews that invested millions of dollars annually (not adjusted for inflation) with the explicit mission of providing economic development projects to support the Jewish economy in Palestine.

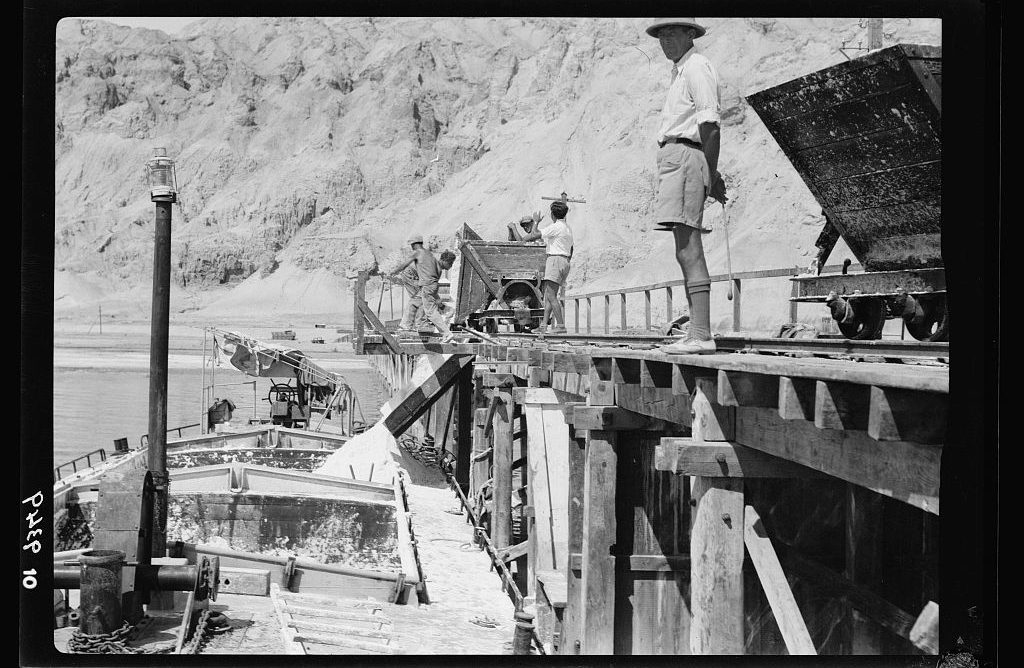

Workers load potash (potassium-rich salt) into a barge alongside the Dead Sea in Palestine in the mid-1930s. Via the Library of Congress.

The scale of this investment was so staggering that in some years PEC investment was comparable to the entire British government’s budget for development in Palestine. (For example, in 1935 the British government spent approximately 2.7 million dollars on development projects in Palestine, whereas the PEC spent 2.9 million dollars.)

The investment was strategically targeted to maximize its impact on the Jewish economy, offering significant aid to some of the most important emerging economic drivers in the region, including Palestine Potash, a company that mined minerals from the Dead Sea; the Palestine Electrical Corporation; and the most profitable agricultural sector in Palestine — citriculture, the cultivation of citrus fruits.

Perhaps more surprising than the scope of the PEC’s investment is the source of its capital. The vast majority of the money for investment came from American Jews who considered themselves non-Zionists, including three of the most important American Jewish leaders of the era: American Jewish Committee president Louis Marshall, influential banker Felix Warburg, and NYC governor Herbert Lehman.

These non-Zionists represented some of the wealthiest and most influential American Jews, who feared that Zionism risked legitimizing the antisemitic idea that Jews couldn’t be true Americans. Rather than take a pro- or anti-Zionist stance, they maintained an agnostic outlook on the Zionist goal of Jewish political autonomy, but nonetheless were willing to aid in the settlement of Jews in Palestine. By channeling their capital into private investment, as opposed to donating to Zionist organizations, these American Jewish leaders hoped to maintain some distance from official Zionist organizations and policies while still supporting the settlement of Jewish refugees from Europe.

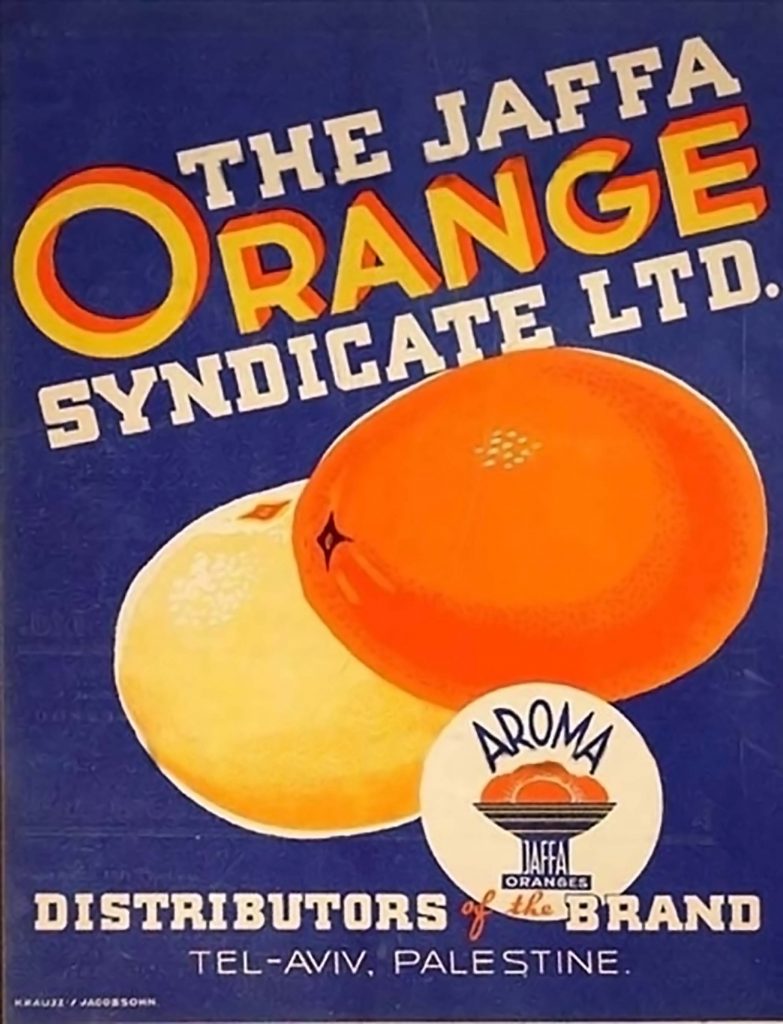

Poster for the Jaffa Orange Syndicate, circa 1930. Via the Palestine Poster Project.

The PEC was more than just an investment institution. In addition to channeling money into Palestine, the PEC sought to apply American technical and agricultural know-how to the region. The PEC brought over representatives from the Florida and California citrus industries to advise on orange packing and marketing. Well-drilling equipment was shipped from the US to help irrigate arid areas and make them fertile for agriculture. The PEC even sent Jewish American bankers to Palestine on a semi-permanent basis to set up a system of credit that would be accessible to Jewish cooperatives, which had trouble securing European bank loans in Palestine and often had to pay exorbitantly high rates of interest, as they were seen as a risky investment.

Ultimately the PEC became a financial behemoth in the region, controlling six subsidiary corporations and becoming a major driver of the rapid economic transformation in the region, which allowed for further Jewish settlement.

For reasons which are not entirely clear, the PEC lost much of its economic clout by World War II. However, its investment activities continue to this day, albeit on a significantly smaller scale. More importantly, many of its investments, including the development of Haifa Bay and Dead Sea mining, continue to have a major economic impact in modern-day Israel.

A broader reconsideration

While the PEC has long since merged with other corporations in Israel, its history feels more significant than ever. Israeli lawmakers who question whether the relationship with American Jews — with whom they often disagree — is worth preserving would be well advised to study the history of the PEC.

While historians and Israeli politicians are largely unaware of it, the Jewish economy in Palestine relied on investment advice from American Jews who disagreed with the very premise of Zionism.

As this history demonstrates, American Jews’ support for Jews in the region hasn’t always aligned with Zionist and nationalist goals. This dynamic continues into the present day, where American Jews’ concern for Israelis can encompass criticism of the Israeli government and of its policies.

Jake Beckert is a third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History and is the 2022-2023 Leo & Mickey Sreebny Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies. Jake’s research focuses on economic development and global capitalist investment in Mandatory Palestine. Outside of academia, Jake is an avid climber and loves living in a region with such a rich climbing history, and such wonderful mountains. When he is not reading in the library or training at the climbing gym, Jake loves to spend time with his pet chihuahua Appa.

Jake Beckert is a third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History and is the 2022-2023 Leo & Mickey Sreebny Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies. Jake’s research focuses on economic development and global capitalist investment in Mandatory Palestine. Outside of academia, Jake is an avid climber and loves living in a region with such a rich climbing history, and such wonderful mountains. When he is not reading in the library or training at the climbing gym, Jake loves to spend time with his pet chihuahua Appa.

Leave A Comment