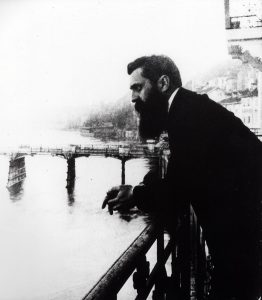

Jewish settlers circa 1920 – commonly known as “HaYishuv” – take a break from building their kibbutz to pose with various construction tools. From the Library of Congress’s Prints & Photographs division.

By Alan Dowty

There is nothing new in the assertion that Zionism is a form of colonialism. More recently, some academic analysts have settled on the definition of Israel as a “settler colonial” state.

Let’s begin with the recognition that such debates are essentially semantic. We need to begin with a definition of settler colonialism, and then determine whether Israel fits the definition. It is similar to the endless debate over whether Israel is a democracy, to which I’ve contributed. Give me your definition of democracy, and I’ll try to apply it to Israel. I only ask that the definition be operational – vague standards don’t help – and that it be applied equally and comparatively to all states.

In that regard, all of the broad comparative ratings of states by political scientists have ranked Israel as a democracy – sometimes a flawed democracy, but more democratic than not. And some of the definitions applied to Israel, in isolation, would disqualify the United States as a democracy if they were applied across the board.

Back to settler colonialism: the early Zionist settlers of the first and second aliyot (1881-1914) did refer to themselves as colonists, a word that did not then carry much of the negative weight that it does today. They were establishing new settlements as part of an organized movement to establish a new national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, something that had not existed since antiquity (despite a continuously existing Jewish population).

It is fair to characterize this settlement as colonization, in the broad sense of establishing settlements in a previously foreign territory. But does it qualify as “settler colonialism”?

Definitions of “colonialism,” as a general concept, usually revolve around the control of one people over another, for economic gain or to impose their culture or religion on the colonized people. There are two important elements to this relationship. The first is the métropole, the mother country of which the colonists are the agents, a sponsor whose economic, cultural, or religious interests are being advanced by the implantation of their own people on foreign soil. The second is the subject population, which is in some respect related to the basic motivation of the colonization.

Prevailing definitions of “settler colonialism” add to this the further implication of an intention to replace, or even eliminate, the indigenous people and/or culture. This goes well beyond the usual motives of domination or exploitation.

Zionism does not fit this model. There was no métropole, no mother country of which the settlers were an extension. Jews who came to Palestine, first from Russia and later from elsewhere, generally fit the accepted definition of refugees who were escaping persecution (at least 80 percent of them by my calculation). In no sense (despite Turkish suspicions) did they represent Russian interests. They sought rather to leave their proverbial Diaspora baggage behind and build a new society based on ancient Middle Eastern roots, including a revived Semitic language.

Secondly, unlike the classical colonialist powers (such as France or Great Britain), Jewish settlers did not include the existing population in their basic design, except as incidental beneficiaries. The presence of another people was first and foremost a major inconvenience, which the early Zionists tried their best to ignore and minimalize, not to dominate or reshape. They did not recognize the Arab population of Palestine as another people with their own collective claims, arguing that as individuals Arabs would benefit from the progress that Jewish settlement would bring.

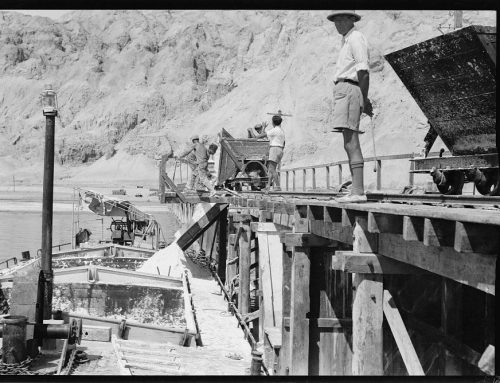

Theodore Herzl looking out over the Rhine at the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. Via the National Photo Collection of Israel, taken by Ephraim Moses Lilien in 1901.

There were occasional voices for “transfer” of Arabs from areas of Jewish settlement, but they were isolated. Far more typical was the response of Theodore Herzl (1960-1904), Zionism’s founding father, who in his famous letter to Arab notable Yusuf Zia al-Khalidi wrote “Who would think of sending [Palestinian Arabs] away? It is their well-being, their individual wealth that we would increase in bringing our own.”

In any event, if displacement of the Arab population was somehow a concealed element of Zionism, it clearly has been an abject failure. This population today, within the borders of Mandatory Palestine, has increased roughly tenfold since the days of the first aliyah.

Finally, Jewish “colonists” were not entering a terra incognita to which they had no historical connection. Whatever weight one assigns to ancient ties, they were seeking to restore to this space the same language, religion, culture, and ethnicity that had prevailed there 2000 to 3000 years earlier.

None of this is said to excuse the indifference of early (or contemporary) Zionists to the existence of another people, with their own valid historical ties, in the same territory. Nor does it justify injustices inflicted on Palestinians in the past or the present.

But this was not “settler colonialism” as usually defined. Better examples can be found in all the countries of the Western hemisphere, Australia, New Zealand, much of Oceania, and historically in Africa and Asia. Or in China’s rule in Sinkiang and Tibet. If there is to be a debate on settler colonialism, let’s expand the sample size.

Alan Dowty is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame and a Visiting Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. From 1963-1975, he was on the faculty of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, during which time he served as Executive Director of the Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations and Chair of the Department of International Relations. From 2003-2006, he was the first holder of the Kahanoff Chair in Israeli Studies at the University of Calgary, and from 2005-2007 he was President of the Association for Israel Studies.

Alan Dowty is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame and a Visiting Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. From 1963-1975, he was on the faculty of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, during which time he served as Executive Director of the Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations and Chair of the Department of International Relations. From 2003-2006, he was the first holder of the Kahanoff Chair in Israeli Studies at the University of Calgary, and from 2005-2007 he was President of the Association for Israel Studies.

Among his publications are basic texts on Israeli society and politics (“The Jewish State: A Century Later“), on the history of Israel (Israel, 2021) and on the Arab-Israel conflict (“Israel/Palestine,” 5th edition, 2023), as well as over 130 scholarly and popular articles. In 2017 he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award in Israel Studies by the Israel Institute and the Association for Israel Studies.

What was written in in your article was only the interesting truth in reference to the early Zionist who come to rebuild their ancient their

For fathers who were exiled from our oldest land where the Jews lived for more than3000 years ago. And thank for explaining that we the Jews are not and never been colonizers.

Israel of today is a zionist state home for for the Jewish nation fron2000 years ago and for

ever after LONG LIVE THE DEMOCRACY OF 🇮🇱ISRAEL🇮🇱

CORRECT. https://besacenter.org/palestinians-settlers-colonialism/

This article is shortsighted of a basic set of facts that demonstrate strong bias. Zionist settlers are a colonial force representing the nation of the children of Israel, it’s citizens. They share a language, and culture identity that in establishing a state in the lands of another and imposing their own laws, and ideals as superior to the existing one in the lands settled are by definition are a colonial settler force.

First, we have to establish what is Israel. What is its constitution and what are her borders. Then we can talk about occupation.

True Israel is not a colonizer but a people in their God given land.

That is stupid and a justification of colonisation in many places like the manifest destiny in the United States.

Your analogy fails because United States didn’t have roots in the western part of the United States.

Would you believe the US has roots to the land if they said “God said so.”?

No, but if artefacts from thousands of years ago were uncovered in the western parts of the United States, with the same language being used by Americans today, I would absolutely believe the US. Debating the claim of the Jewish people over that land is understandable. Debating the fact that Jewish people lived and flourished there for many many years in the past is ignorance.

Flawed premise. God is an unproven entity. Whose god is the real god.

Argument of God was in context and has nothing to do with your belief.

God is not a realistic or credible justification for a harmful colonialist phenomena.

I can appreciate the views you are putting forward, but in the end I still view it more akin to colonization than anything else. My reasoning for this can be summed up in a few points. First, this is not an act of simple emmigration since the idea from the begining was to set up a different government than the one that was already present there. Second, colonization comes in different forms. To make a parallel example it’s like economic systems. The United States and Germany have entirely different modes of government and laws that determine how their economy works, however they are both capitalistic societies. The same thing is true of Maoist China and the Soviet Union both being Communist. Similarly, the acts that one takes when colonizing another land will always look different from each other. That brings me to the final flaw that in your argument. Simply not being an entity of a larger government does not preclude you from being a colonizer. The United States is not part of England and conquered the majority of the area that is now the US after declaring independence from England. In fact most Americans that colonized the vast majority of that land were not British, but rather immigrants from other parts of the world that came later after the US’s war for independence. Does that somehow mean that all of the US excluding the original 13 colonies was not colonized at all? That would be a very arbitrary distinction to make. At the end of the day, if you establish a new state with new laws in an area where someone else already lives, you are a colonizer. Either that or close enough to one that any distinction being made between the two is not being made in good faith.

This article is beyond parody and a textbook example of acedemic pedantry. How can you call yourself a historian and not even mention the Nakba when talking about Israel and settler colonialism. Its a despicable lie by omission when you consider what Israel is doing right now to palestinians and what it has done in the past to them.

This was my exact same thought. Zero mention of the hundreds of thousands of ‘inconveniences’ displaced.

The period he is referring to was before the Nakba happened. He was discussing the first immigration by Zionists to the land and what thier views and motives at the time were. The Nakba is a different story that happens later on.

“A different government than the one that was already present there…”

So… British Mandatory Palestine? As in the British Empire? Not sure what your point is here.

Israel is a settler-colonial ethno-state. Zionist organizations founded by Theodore Herzl, for example, named themselves “colonization associations,” such as the “Jewish Colonization Association” and “The Palestine Jewish Colonization Association,” which is also known by its Yiddish acronym PICA. Nor was there any attempt to disguise the true goal of Zionism when its leaders named the “The Jewish Colonial Trust,” which was founded in 1899.

The author addressed this exact point pretty clearly above.

The moment the State of Israel was declared a nation state it became settler colonial. There is no requirement for a metropole – that is only for extractive colonial activities. Most of N America was settled by immigrants fleeing the metropole. If the early settlers to Palestine had been satisfied with living together with the indigenous Arab population (most of whom have genetic links to Jews if Ancestry.com is to be believed) and creating a new entity where both had equal rights, it could have become a place of immigration. The State of Israel, however, necessitated the removal of large swathes of Arab populations and continues to push the boundaries of the territory, which is part of the definition of settler colonialism. It has become explicit Israeli policy to regain Judea and Samaria (most of the West Bank) – the ‘settlements’ (the clue is in the name) are exactly settler colonial projects.

Literally it’s not even up for debate. Israel was created as a colony (for British control) and defined as a colony by Hertzl himself. Secondly , the assertion that Jews settling and creating Israel would provide wealth is simply been proven to be false as they have not increased income per capita and have secondary rights compared to Jewish “nationals.” They have also had assets claimed by eminent domain of the state authority for settlers.

This is a really weak analysis for a professor.

‘ In 1898, Theodor Herzl recognized that, in order to establish a “Jewish state” in Palestine, the inconvenient indigenous population would have to be removed. “We shall try to spirit the penniless [Palestinian Arab] population (i.e. Arab) across the border,” ‘

Plenty more of this…

Whereas the Jews have inhabited the lands now known as Israel/Palestine continuously for thousands of years, how is it not the Muslim Palestinians who are the colonizers? Isn’t it that the Jews are reclaiming the land that was once theirs, and would still be theirs, had it not been for successive pogroms that drove them from those lands over those thousands of years?

This proposition is not meant to justify the forced displacement of three quarters of a million Arabs from their homes in 1948, or any of the actions Israel has taken against the Palestinians since, but it is meant to challenge the predominant “Progressive” narrative that the Jews are no more than newly arrived “settler colonials” with no prior claim to this territory. This debate is not as simple as many would like the world to believe it to be.

Sharing a religion with the ancient judeans doesn’t make today’s settlers the judeans’s ancestors. That is a preposterous claim. Religion is not ancestry. And even the government of israel knows it, because they don’t accept DNA tests as proof of jewish ancestry! You could be a direct descendant of King Solomon himself and it wouldn’t matter one bit to the government of Israel. Religion is NOT constitutive of direct ancestry, sharing a religion with someone doesn’t make them your ancestor, and it especially doesn’t give you claim to the land of people who weren’t even your ancestors.

MKs Danny Danon and Ram Ben Barak wrote that the West should take refugees from Gaza. The proposal was also welcomed by minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, follower of Meir Kahane, who advocated expelling Arab Israelis, as well as the Palestinians from Israel and the territories around it. Agriculture minister Avi Dichter said “we are now rolling out the Gaza Nakba”.

So maybe it’s wasn’t settler colonialism then, but it is now.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/hamas-sees-peace-as-weakness-israel-war-in-gaza-civilian-deaths-9027c01d

Palestine was colonized by the British Empire. Israel just inherited it.

It doesn’t change the impact on the people that were living there.

Before the canal, you got to Asia across land to Suez, Aqaba, or Kuwait; or you sailed around Africa.

Britain needed status in the Ottoman Empire and a religious claim on the holy land was politically expedient. Russia had the Eastern Orthodox and France had the Catholics. Britain had the Anglican Church which couldn’t trace its roots back to Palestine.

The Israeli narrative relies very heavily on the historic land claim. Yes, they faced a time of great need when 2/3 of their population were wiped out. No doubt. But putting forth a thousands year old claim on land is odd. I would argue that it’s also not Jewish, it’s British… and the claim predated WWII by over a century.

When the British Consulate to Jerusalem was set up in 1838 (twenty years before construction of the canal began), the application was amended to include British protection of the Jews. Again, the French had the protection of the Catholics and the Russians had the protection of the Eastern Orthodox.

This protection was extremely important to Nicholas I who was landlocked without the consent of the Sultan who controlled the Turkish straights in Constantinople. In addition, he had just come off a string of military victories against the Ottomans which was very alarming to the British and the French when considering the “Eastern Question.” As the Ottoman Empire fell, the Russians had to be contained.

The other player in the game was Muhammad Ali who had just wrestled Egypt away from Napoleon and then, the Sultan. Palestine held a strategic position between Egypt and Russia in the disintegrating Ottoman Empire.

By adopting the Jewish cause, the British were able to strengthen their claim on the Holy Land. In fact, they quickly expanded their protection to include Rayah (native) Jews instead of only Jewish immigrants from Europe.

When Montefiore toured Palestine in 1840, he was given an armed escort. The prevalent feeling was that, unless sheltered by the European Powers, the Jews in Palestine would face “utter annihilation.” The protection most desirable was that of Great Britain. The English “will administer justice… till the Messiah comes.”

You all know what happened next: Herzl, Balfour, Sykes, Churchill, Ben-Gurion, and on and on.

Now the US has assumed the role of protector and the IDF has taken on the role of administering justice.

Regardless of when you start the clock, the native Palestinians have suffered and continue to do so… hopefully not until the Messiah comes.

Why are there no cited sources?! Seems very dishonest to publish a historical analysis that promotes or even neutralizes a certain political ideal without offering any evidence or academic bibliography.

The author of this essay, Professor Alan Dowty, has written several books about the Arab-Israeli conflict, including an introductory text called “Israel/Palestine” (Wiley, 2008). You can read selections of “Israel/Palestine” online via Google Books: “Israel/Palestine” book online.

Palestinians are descendants of Canaanites. Netanyahu is Polish-Russian. How come there are no other people with a super light complexion in the Middle East besides Israelites? It’s because Israelites are not from the Middle East. The only reason their interests are being protected by USA is because they are a central point against Russia so to avoid the spread of communism or socialism in the Middle East. Why else does far right extremism and geopolitical capitalism thrive there… because of the USA and Israel.

Natanyahu is an Ashkenazi Jew and therefore has lighter skin than most, though not all, Palestinians. Both he and they are likely to share a similar amount of ancient Canaanite DNA. A majority of modern Israelis (Israelites are the people in the Bible) are descended from the Middle Eastern/North African Jews expelled from countries like Iraq, Yemen and Algeria. They are generally as brown as anyone else in the region, sometimes more.

Not sure about your worries about communism or are you stuck in the 60s?

These are simple facts. Actually think!

The Zionist project is a long, complicated and contradictory story that can’t be captured in simple cliches. It was both a nationalist movement and “white” settler colony. It was also a desperate flight of refugees, a utopian community, a religious revival, and a case if exploitation. It started in the context of the Ottoman empire, continued under British and imperialism and for the last 50 years has been enmeshed in the American imperium. The Palestinian national movement also has a long, complex history. There have been openings along the way for both Jews and Arabs to live together in peace and failure to do so can’t be blamed on any single cause.

“ In any event, if displacement of the Arab population was somehow a concealed element of Zionism, it clearly has been an abject failure.”

Huh? With help from the Hagana and the Irgun – precursors to the IDF – the Zionist leaders of mandatory Palestine forcibly expelled hundreds of thousands of Arabs and forbade them from returning. The fact that the remaining Arab population has grown (by outpacing reproduction among Jewish Israelis) is completely irrelevant to their forcible displacement. It’s hard for me to consider that oversight innocuous on your part. Thanks.

“If there is to be a debate on settler colonialism, let’s expand the sample size.”

Yes, why not avoid the topic completely.

The author states: “We need to begin with a definition of settler colonialism …” yet does not attempt to define it himself. He also asks for a definition of democracy, without offering one himself.

Whatever the history, the fact is that since 1945 or earlier the Israelis have perpetuated violence against Palestinians. The Hamas action in Israel was inexcusable, but was possibly the result of frustration of decades of extreme violence by Israelis towards Palestinians. This is not about religion, it is political. Why must innocent children pay the price of adult childishness?