A tour group in the main exhibition space at the Holocaust Center for Humanity in downtown Seattle. Photo credit: Katja Schatte.

Bridging the Particular and the Universal—Without Erasing Either

Seattle’s recently inaugurated Holocaust Center for Humanity (HCH) demonstrates that teaching a bigger lesson does not have to come at the expense of representing a particular history. With its focus on the stories of local survivors, the center not only bridges the gap between the particular and the universal, it also demonstrates that the respect for, not the erasure of, particularity lies at the root of solidarity.

The Holocaust Center for Humanity’s own history is just as important as the history it represents. It leaves no doubt about how central the role of Holocaust memory and the fight against antisemitism are to its mission. Twenty-six years ago, a group of local survivors founded the center’s precursor, the Speakers’ Bureau, to tell their stories at local schools and universities in response to spreading Holocaust denial. Until this day, the Speakers’ Bureau and the recording of oral histories are vital parts of the Holocaust Center’s work.

However, in the face of diminishing numbers of survivors, the Center has come up with new ways to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive. But instead of giving in to what Professor Walter Reich calls “the itch to universalize,” the HCH continues to focus on the stories of Jewish survivors throughout its recently inaugurated exhibit. And instead of forcing the exhibit to choose between teaching about Jewish suffering during the Holocaust and teaching bigger lessons, the survivors’ stories accomplish both at the same time.

As Dee Simon, the Center’s Executive Director, summarizes it: “We learned that students learn best from stories. People learn best from stories. And the richest thing we have is the stories of survivors. That is what makes our museum unique: Holocaust stories from people who survived and came to live here.” As a result, the artifacts on display in the museum are also always “a symbol of someone’s story.”

The Center’s commitment to both preserving these artifacts and making them accessible becomes apparent in its cutting-edge archival infrastructure. After two major institutions, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington D.C. and the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, Seattle’s HCH is only the third institution in the United States to meet the strict preservation standards of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Collection in Oświęcim, Poland and thus has obtained artifacts from that collection.

Items from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Collection are on display at Seattle’s Holocaust Center for Humanity. Photo credit: Katja Schatte.

Just as important as the preservation and display of the artifacts is the content of the stories the museum tells with them. As Dee Simon explains, specific curatorial decisions ensure that human experiences of the Holocaust, rather than sanitized historical timelines, structure visitors’ experiences of the exhibit. With the exception of a few images from the USHMM, all objects in the HCH exhibit tell the stories of local survivors. Rather than presenting history from the perspective of informed hindsight, the exhibit guides visitors through the lived experiences of identification, exclusion, the turning point of Kristallnacht, flight and rescue, and the mass murder of European Jews in the ghettos and concentration and extermination camps across Europe. Survival, too, is presented as part of the narrative. Ultimately, the exhibit succeeds in answering the oft-asked question “But why did no one see it coming?” by helping visitors understand how members of the European Jewish community experienced history as it was happening.

Holocaust and Lessons of Solidarity

After traversing the exhibit, extending the perspective to other victimized groups and genocides no longer seems like a justification for the engagement with Jewish suffering; rather, it is the logical next step. The strength of the exhibit is precisely portraying the Holocaust as more than a universalized example of evil. And it is the very particularity of the history on display that provides a starting point for solidarity.

This is a kind of solidarity that is not one-sided, as both the history and the future of the exhibit demonstrate. Over the many years when the Holocaust Center did not have its own exhibition space, its traveling exhibits were on display at different institutions across Seattle. Starting in the fall of 2016, the Center will house a small collaborative space, inviting organizations from across the world to display their exhibitions addressing different instances of persecution throughout history, starting with the exhibition “Homosexuals and the Holocaust” in September.

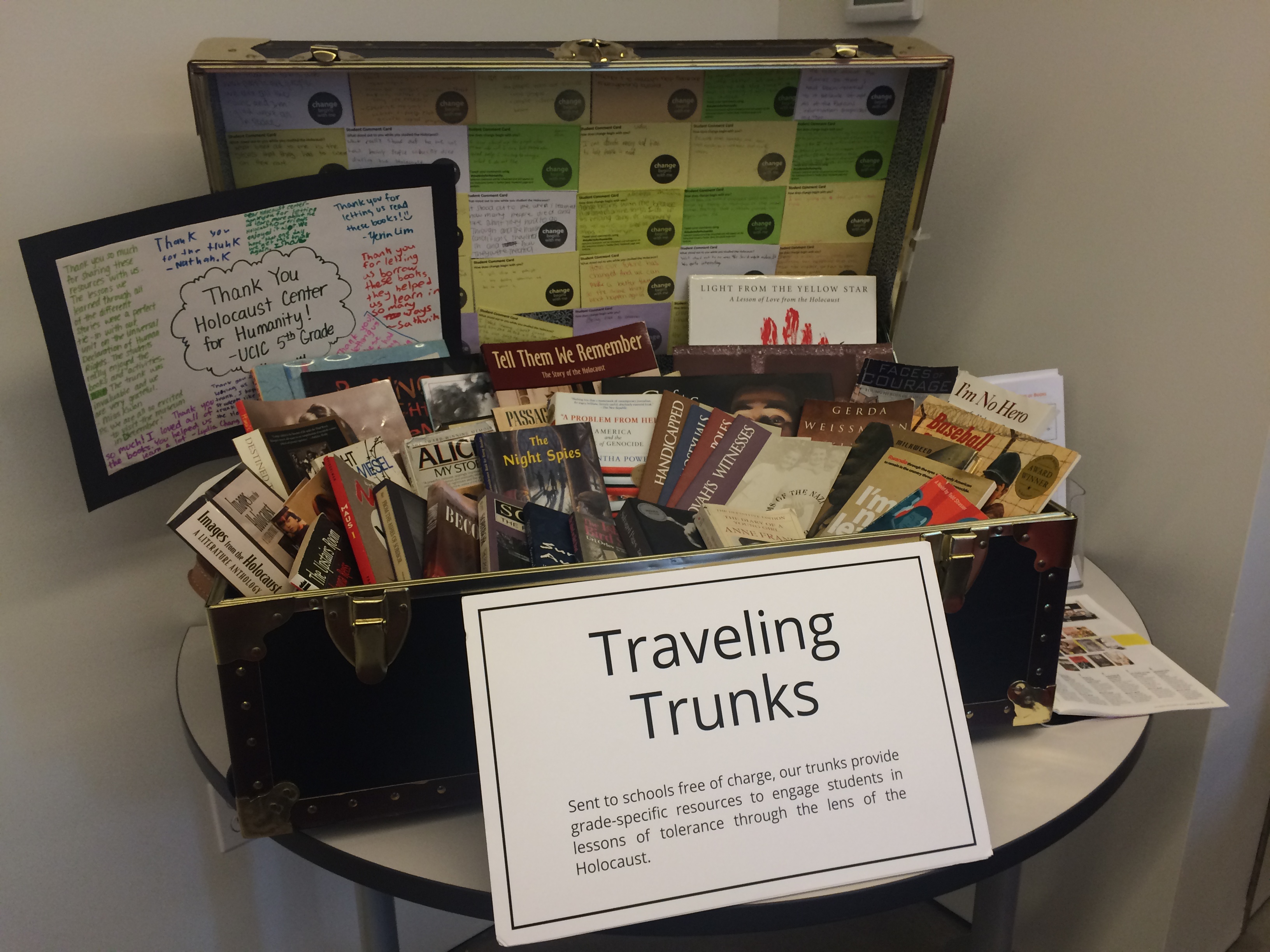

The centrality of the survivors’ stories—in the exhibition hall, the Center’s teaching trunks, its ongoing speakers’ series, and its project highlighting the voices of the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors—leaves no doubt that Jewish persecution and genocide are at the heart of the exhibition. In its teaching of the bigger lessons, the Center’s commitment to individual stories is as firm as its representation of the Holocaust itself. After all, the refusal to acknowledge individual guilt and responsibility has obstructed a personal engagement with the history of the Holocaust among the perpetrators, the bystanders, and their descendants over generations.

Teaching Trunks available at the Holocaust Center for Humanity help with educational outreach. Photo credit: Katja Schatte.

So when the HCH states that “Change begins with me,” rather than an erasure of the Jewish suffering in the original tragedy, it is an acknowledgment that individual actions are the key to preventing its reoccurrence. Because as historian Marion Kaplan writes in her groundbreaking work Between Dignity and Despair: “Well before the physical death of German Jews, the German ‘racial community’—the man and woman on the street, the real ‘ordinary Germans’—made Jews suffer social death every day. This social death was the prerequisite for deportation and genocide.”

Student comments on display in the museum indicate an awareness of the power of individual actions to resist dehumanizing mass ideology. However, Richard Takaki, a museum visitor who was deported to a Japanese-American internment camp with his family when he was four years old, remains concerned about the power of this kind of ideology, pointing out instances such as the isolation and deportation of his own community, the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, and recent calls to keep Syrian refugees out of the United States.

Fortunately, institutions like the HCH are not alone on their mission to teach lessons in solidarity. In the Seattle area, local Japanese-American organizations and their partner institutions, such as the Japanese Cultural Community Center of Washington, the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community, and the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum, have undertaken their own efforts to combine the memory of their particular history and broader conversations about community, humanity, and human rights.

Seattle’s new Holocaust Center for Humanity thus does not universalize the history of Jewish suffering during the Holocaust. Instead, it sets out to ensure that the promise of “Never Again,” which Professor Reich rightfully calls “a staple, even a cliché, of Holocaust education,” will become more than a catchphrase.

Leave A Comment