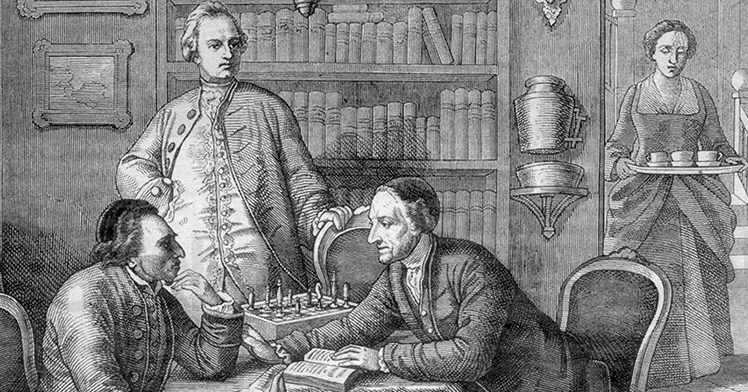

Moses Mendelssohn (left) discusses theology with Johann Kaspar Lavater and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Noam Pianko

Who is the most important and influential Jewish thinker in the modern period?

There are certainly many possible answers to this question. However, there is a good argument to made for the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Kant was certainly not Jewish. But I like to jokingly refer to him as “Rabbi Kant” because his writings on what it means to be a modern, enlightened person shaped the contours of modern Judaism across the ideological spectrum–from thinkers that embraced the Enlightenment to those that radically rejected this movement.

Immanuel Kant, Enlightenment thinker.

Kant enumerates the three primary principles of the Enlightenment in the essay we read together, “What is Enlightenment?”:

- 1) Autonomy – the ability to think for oneself

- 2) Reason – the ability to understand the world through rational inquiry

- 3) Universality – the ability for individuals from across cultures, religions, and geographies to come to the same conclusion about fundamental human questions

These principles have had a significant impact on Judaism, as a textual tradition that places a tremendous weight on knowledge passed down from generation to generation, all the way back to God’s revelation at Mt. Sinai. Traditional notions of what Judaism is (the covenant between God and man outlined in the written and oral Torah) appear to be fundamentally incompatible with Kant’s vision of what the Enlightenment is.

Modern Jewish thought emerged to demonstrate the compatibility between Judaism and the Enlightenment principles of autonomy, reason, and universality. In my courses, I look at a classic formulation of this position articulated by Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) in his book Jerusalem. Mendelssohn delicately addressed the relationship between commandment and autonomy, revelation and reason, and particular practices and universal knowledge. Jerusalem argues that Judaism is uniquely compatible with Enlightenment thought because Judaism (unlike other religions) does not demand any belief that might threaten an individual’s autonomy, reason, or commitment to universal truths. Judaism centers its expectations on action rather than belief. Thus, Judaism as a religious tradition fundamentally shares the unchanging truths of philosopher about issues related to “eternal concerns.”

By solving one problem (the compatibility between Judaism and Enlightenment), however, Mendelssohn introduces another: why remain Jewish if the tradition doesn’t have unique access to particular truths? Mendelssohn’s answer affirms Jewish ritual and tradition as a path for guiding Jews toward the eternal truths of the philosophers: Jewish practices create a set of valuable tools for guiding modern Jews toward living an Enlightened life.

Mendelssohn’s response to the Enlightenment left us with a final question: Is an instrumental definition of Judaism sufficient to sustain Judaism in the modern period? In grappling with this question, twenty-first-century Jews remain deeply in conversation with “Rabbi” Kant and the tensions introduced by the Enlightenment.

Re Universality, what are the ‘fundamental human questions’?

What I’m really asking you is:

Where do you find the phrase ‘fundamental human questions’ in Kant’s essay ‘Enlightenment’?

Or do you find that only in Cassirer’s book: Philosophie der Aufklärung (1932) — NO

.

However, the questions are written in ‘The Philosophy of Ernst Cassirer: A Novel Assessment

p.268 Pierre Keller: What can I know? [metaphysics], What ought I to do?[Morals],

For What can I hope?[Religion], and What is a Human Being?[Anthropology].

Kant’s 1798 ‘Pragmatic Anthropology’ deals with the fourth question.

Religions don’t answer these question, because religions are actually military-cultural dictatorships.

If a religion tells you ‘Don’t eat pork burgers!’, that means OBEY – DON’T DISCUSS IT.

The range off acceptable questions is always extremely limited.

According to Kant, Enlightenment is mainly up to you.

If a religion tells you ‘Don’t eat pork burgers!’…. It means Be a good Jew, whose very existence is the testimony of the existence of G-d.