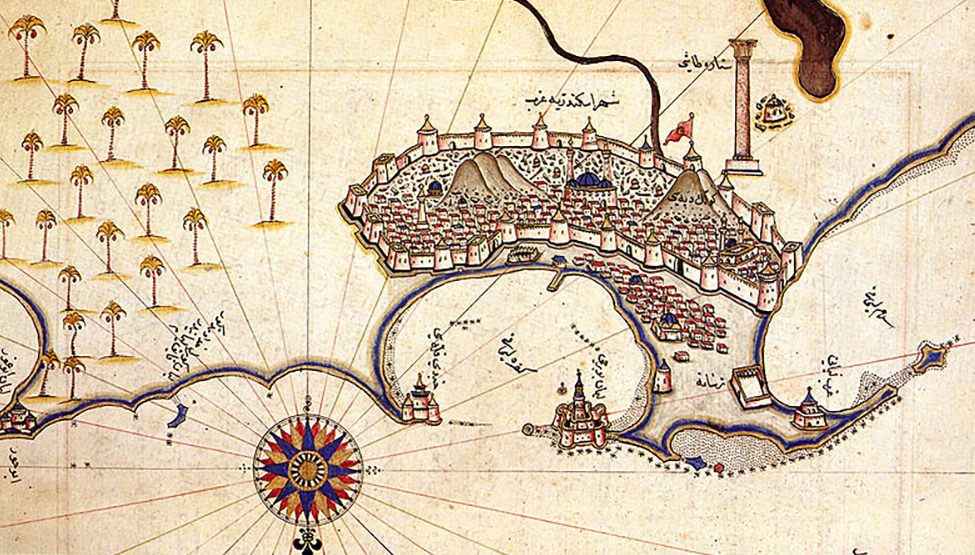

12t- century map showing the northeastern edge of Egypt (north facing down) and the port at “Al Iskanderia” (Alexandria) along the coast. Part of the Tabula Rogeriana, drawn by geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi for Roger II of Sicily in 1154.

By Brendan Goldman

When Whoopi Goldberg recently characterized the Holocaust as an event that was “not about race”—“[it was] white people doing it to (i.e., killing) white people” — she was widely rebuked for her ignorance of the role of Nazi racial eugenics in the genocide of European Jewry. But Goldberg is hardly alone among Americans in her belief that Jews are white people whose narratives are not relevant to contemporary issues of discrimination in the United States.

As the Hazel D. Cole Postdoctoral Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington, I study the history of the persecution of minorities in the context of Jewish subjects of Muslim rulers in the premodern Near East. My research illuminates how premodern acts of anti-Jewish popular and police violence have striking parallels to discrimination in modern U.S. history.

Events over recent years have reminded us how state-sanctioned violence in the form of police brutality has degraded and terrorized Black Americans. The central reason Black citizens have been and still are the primary victims of such state violence is that the levers of American government power work on behalf of the white majority.

This power differential and its associated violence — not arbitrary melanin concentrations or racial pseudo-science — are what make marginalized groups like Black Americans and Near Eastern Jews “minorities.”

Violence as a reinforcement of social hierarchies

For 2,000 years, Jews were in many ways the quintessential stateless minority in the Roman and then Islamo-Christian worlds. Jewish statelessness is not merely a refrain — it shaped Jews’ everyday lives, often denying them the police protection and security granted to the majority.

The Christian and Muslim rulers I study allowed Jews to live among them as second-class subjects because Jews had a special role to play in Islamic and Christian sacred history; namely, the humiliated state of Jewish communities under Christian and Islamic rule testified to God’s punishment of the Jews, who had failed to embrace the true faith.

These rulers permitted or actively facilitated violence against their Jewish subjects to exhibit the majority’s hegemonic power, broadcasting to even the lowliest Muslim or Christian that they were favored over even the most wealthy and influential Jew.

Map of the port city of Alexandria, Egypt, circa 1528. North is down. The famous lighthouse of Alexandria is pictured at the right. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Violence against Jews in the medieval world — like 19th- and 20th-century violence against Black Americans — often erupted in contexts where Jews were accused of acts that violated the social hierarchy, like a Jewish man sleeping with a woman of the privileged majority.

Mob violence against Jews in 12th-century Egypt

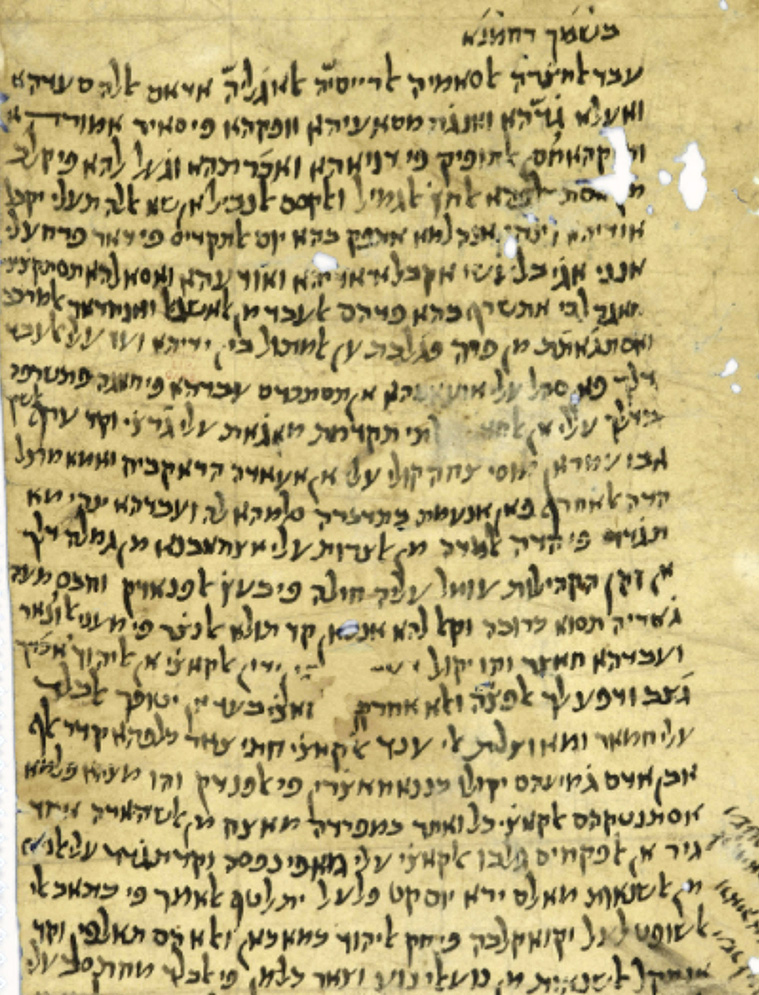

A number of such incidents are recalled in letters and court deeds from a remarkable synagogue repository known as the Cairo Geniza. In the letter shown here, for instance, a leader of the Jews of Egypt’s premier port, Alexandria, wrote to a fellow Jew at the Egyptian capital, Cairo, explaining the genesis of an anti-Jewish riot in Alexandria in the 1140s CE. The relevant part of the document reads:

The letter from Alexandria, a document discovered in the Cairo Geniza. View in University of Cambridge Digital Library (T-S 13J13.24).

“An act of subterfuge was committed against a distinguished leader of the (Jewish) community at one of (Alexandria’s) inns.

(The Jewish leader) was imprisoned with a worthless (Muslim) girl. The policeman spoke to the girl about the matter of unlawful sexual relations… Her slave came and said: I bear witness to the judge that the Jew raped you and then paid you (for sleeping with him)…

When (the girl) arrived at the judge’s court, a thousand people followed in her wake and all of them (bore witness and) said: we came to the inn and (the Jew) was (having sex) with her. But when the judge cross examined (these witnesses) individually, (he found) there was no truth to any of their testimony.

Nevertheless, the secret police prevailed upon the judge, convincing him to go against his conviction. So anti-Jewish violence reawakened among the people such as had never been seen before… Already this hatred has spread from one group to another such that everyone in the city has become a policeman (muḥtasib) over the Jews…”

What had happened? The secret police had accused a Jewish elder of committing a crime—namely, sleeping with a Muslim woman — at an inn, a common site of prostitution. The Jew and the Muslim were subsequently arrested and detained at the inn.

One of the policemen then brought to the Muslim woman’s attention the consequences of having sex with a Jew; namely, that the crime was punishable by death. Subsequently, the woman convinced her slave to come and claim that the Jew had raped her.

The woman and/or her slave then spread a rumor across the city about a Jew raping a Muslim woman. A mob of Muslim “witnesses” flooded the court to demand justice be exacted from the Jew.

The judge at first rejected the farcical claim of a mass of witnesses to a private sexual act, but then yielded to pressure from the secret police and the Muslim mob, ruling that the Jew was guilty.

Following the guilty verdict — and perhaps the “rapist’s” imprisonment or execution — a riot broke out against Alexandria’s Jews. The police, the letter tells us, allowed the violent mob to act in their name, deputizing the Muslim rioters as “police(men) over the Jews.”

The timelessness of state-sanctioned violence against minorities

There is something oddly resonant to American ears about an episode in which a spurious accusation against a minority “rapist” leads to a confluence of state and mob “justice” and a popular riot against the “rapist’s” marginalized community.

Indeed, the previous sentence could just as easily describe what happened to the affluent Black community of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921 as what occurred to the Jews of mid-12th-century Alexandria, Egypt. What makes the Jewish experience in medieval Alexandria and the Black American one in 20th-century Tulsa “minority experiences”?

In both contexts, state institutions tasked with protecting minority subjects instead sided with a mob of the privileged to facilitate the destruction of minorities’ lives and property. That is also what occurred in czarist pogroms against Jews in Russia; popular Hutu massacres of Tutsis in Rwanda; and slaughters of Bosnians, Serbs and Croats in the Balkans, among many other incidents around the world and throughout history.

When we contextualize state-sanctioned violence against Black Americans within the history of persecution of Jews and other minorities, we see that while scientific racism is the product of the past few centuries, the justifications and goals of state subjugation of minorities recur throughout history.

This context demands we interrogate our own place as possible beneficiaries of this state-sanctioned violence. It also demands that we incorporate Jewish narratives into discussions of minority experiences, both past and present.

Watch Brendan Goldman’s recorded lecture on the disproportionate imprisonment of Jews in medieval Cairo: “Minorities & State Violence: The View from the Jews of Medieval Cairo”

Brendan Goldman is a historian of the Jewish communities of the medieval Islamic world and a specialist in the documents of the Cairo Geniza. He received his Ph.D. in history from The Johns Hopkins University in 2018. His first book, “Camps of the Uncircumcised: The Cairo Geniza and Jewish Life in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem,” is under contract with University of Pennsylvania Press. His second book project, tentatively titled “A Disciplinary Society: Medieval Prisons through Jewish Eyes, 1000-1300,” examines how Cairo Geniza documents can illuminate the ways state violence shaped the lives of everyday people during the Middle Ages. He is the 2020-2022 Hazel D. Cole Postdoctoral Fellow in Jewish Studies at the University of Washington.

Brendan Goldman is a historian of the Jewish communities of the medieval Islamic world and a specialist in the documents of the Cairo Geniza. He received his Ph.D. in history from The Johns Hopkins University in 2018. His first book, “Camps of the Uncircumcised: The Cairo Geniza and Jewish Life in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem,” is under contract with University of Pennsylvania Press. His second book project, tentatively titled “A Disciplinary Society: Medieval Prisons through Jewish Eyes, 1000-1300,” examines how Cairo Geniza documents can illuminate the ways state violence shaped the lives of everyday people during the Middle Ages. He is the 2020-2022 Hazel D. Cole Postdoctoral Fellow in Jewish Studies at the University of Washington.

Leave A Comment