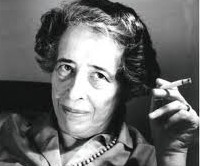

Prof. Michael Rosenthal is Chair of the UW Dept. of Philosophy and a Jewish Studies faculty member.

An Interview with Prof. Michael Rosenthal

Editor’s note: The controversial 20th-century philosopher Hannah Arendt is the subject of a series of UW events in late October, all organized in conjunction with the Oct. 24 Walker-Ames Lectureby noted Yale University political philosopher Seyla Benhabib. Benhabib’s lecture will address “Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: Fifty Years Later.” On Oct. 22 the Stroum Jewish Studies Program is hosting a free film screening of “Hannah Arendt,” the 2012 biographical film directed by Margarethe von Trotta. Click here for more information.

Here is our new interview with Prof. Michael Rosenthal, chair of the UW Dept. of Philosophy and a Jewish Studies faculty member, where he explains the key historical background about Hannah Arendt’s work on the Eichmann trial and its continuing impact. Prof. Rosenthal will moderate the post-film discussion on Oct. 22.

German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt attended the war crimes trial against Adolf Eichmann in the early 1960s and reported on it for the New Yorker.

1) Who was Hannah Arendt? Why is there a movie about her?

Hannah Arendt was a German-Jewish political theorist and philosopher who had an impact far beyond the academy. She was born in 1906 in Hanover and died in 1975 in New York. She received a classical education and studied philosophy at Marburg with Martin Heidegger. When the Nazis came to power in the 1930s, she was forced to emigrate, first to France and then to the United States. After some initial difficulties finding a job, Arendt eventually became an influential professor, primarily at the University of Chicago and the New School for Social Research. Her work received widespread attention in part because of the controversy around her report of the Eichmann trail in Jerusalem, which she wrote for the New Yorkermagazine and later published as a book. It is relatively rare for a philosopher to be the subject of a movie, but Arendt’s comments on the trial and her analysis of the evil perpetrated by Eichmann created some real drama.

2) Who was Adolf Eichmann?

Adolf Eichmann rose from a lowly background to become a high-ranking bureaucrat in the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel or Defense Corps). He was in charge of the deportation of European Jews and involved in the planning of the “Final Solution” – the systematic murder of millions of Jews and other people during the Second World War. At the end of the war he managed to escape from US custody and with the help of the Catholic Church fled to Argentina, where he lived under a variety of aliases, until the Israeli secret service, the Mossad, captured him in 1960 and brought him to Israel. The Israelis accused Eichmann of crimes against the Jewish people and put him on trial in Jerusalem. He was found guilty, sentenced to death, and hanged on May 31, 1962.

The trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel, which Hannah Arendt attended.

3) What was the background of the Eichmann trial?

It is important to remember that in the period after WWII there had been relatively little public attention paid to the Holocaust. The Nuremburg trials in the late 1940s had sentenced several leading figures of the Nazi party for war crimes and crimes against humanity. And some other, lower-level figures had been tried in the occupied zones of Germany as well as in countries that had been under occupation. But it wasn’t until the Eichmann trial that the world focused on the atrocities committed against the Jews. The Israeli authorities had a difficult task: how to provide a proper trial while at the same time educating the public about the systematic crimes of the Nazis. The feeling of many in the Jewish community—those who had survived, those who were lucky enough to have escaped before the war, or who lived outside of Europe in the United States—were very raw.

4) What was controversial about Hannah Arendt’s coverage of Eichmann’s trial?

Arendt walked into the situation with unique credentials. She had grown up in Germany and had lived through the rise of fascism and the disaster of the war. In the 1930s she had worked in France to helped Jews emigrate to Palestine and the US, and in the 1940s she wrote regularly about Jewish politics. As she put it in a subsequent interview, her goal was to understand the trial and not to use it for political or other purposes. Like the classical figure of the philosopher Socrates, who said what he thought, even though it was unpopular and got him into trouble, Arendt spoke what she perceived as the truth, regardless of public opinion.

5) So what did she say in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil?

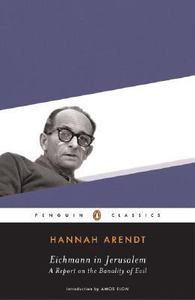

You need to read the book! But there are two big points I can summarize here. The first was a philosophical point: she formulated the concept of the “banality of evil.” The second was a historical point: she pointed out that some Jewish leaders in Europe had effectively helped the Nazis during the war. Although the first point is surely her most significant and lasting contribution, it was really the second point that ignited the controversy at the time and overshadowed everything else.

Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, which will be discussed at the UW Walker-Ames Lecture on Oct. 24.

Arendt liked to say that she had not brought up this issue but had only reported what the Israeli prosecutor had mentioned in a cross-examination. Still, because Jewish feelings were so raw, it appeared to most everyone at the time that her critical statements about the leaders of ghettos were grossly unfair and lumped the persecuted among the persecutors. It seemed wrong to deflect attention from the evil deeds of Eichmann and focus on the actions of Jewish leaders who had been in a terribly difficult situation. In a subsequent exchange of letters, the prominent Jewish historian, Gershom Scholem, himself a German émigré to Palestine, accused Arendt of not having a love for the Jewish people (Ahavath Yisrael). Her response was illuminating: she replied that it was impossible for her to love a people and she could only love family and friends. The implication is that love of a people requires that a person give up a measure of their critical intelligence and be willing to bow to the needs of a fickle public. As a philosopher that would be impossible for her to do. She suffered personally from the vitriol and scorn that was poured upon her as a consequence of her courageous stance to think for herself and reserve the right to make her own judgments on the basis of reason and fact.

thank you! very informative. provided necessary background for the reading.

Thank you for the informative piece.

What happened until 1962? Why did the Holocaust not recieve enough public attention until the trial?