“My dear pupil, ever since you resolved to come to me, from a distant country, and to study under my direction, I thought highly of your thirst for knowledge…” –Maimonides

There was (and I imagine still is) a paucity of Jewish features in the community where I spent my formative years. I didn’t have any Jewish friends growing up. I never knew anyone in my community to be Jewish. There was no synagogue in my community. There was an insufficient understanding of Judaism and knowledge about Jewish culture, notwithstanding the ubiquitous practitioners of the Judeo-Christian tradition. For all of that articulation of the Word, I had little sense of what the Judeo half of that equation was all about.

Sketch of Russian writer Isaac Babel by Yuri Annenkov.

I was born just north of Kansas City in Smithville, Missouri; a name that suggests the founders of this town were beholden to making it as commonplace as possible. My family moved to Alaska when I was two. After living there for a handful of years my family moved back to the Midwest; this time just down the road from where I was born to a town called Liberty. Liberty is a community that over the last several decades has grown into the expanding ring of small towns that are considered Kansas City’s bedroom community. This is where I grew up and spent most of my adult life.

If one were to plot a line between the mean center of the U.S. population (Texas county) and the geographic center of the United States (Lebanon, Kansas), you would find where I grew up located on that line approximately in the center of those two centers. Centrality played, and continues to play an important role in the development and durability of Kansas City’s metropolitan area communities. This is a hub: in the history of American expansion it was a major waypoint drawing and propelling people from sea to shining sea. Communities all throughout the American West can be linked to this area, specifically to Independence, Missouri; the terrestrial berth that harbored and launched so many armadas of covered wagons sailing along the Santa Fe, California, and Oregon trails. Despite the massively logistic grounds for it, a diverse assembly of peoples did not permanently settle here, and the community I remember growing up in was insular.

It was the horizons of my native land that attuned my soul to travel. The head turns and the land lays bare a path in all directions. Above, a blue and boiling map; an animated curling fluidly unfolding topography of rivers and roads betrayed by streaming vapor. Thus, the aspects out and up gave rise to a certain kind of wanderlust. Lacking any real means of mobility in my youth, I let my eyes travel across pages and found recourse in books to feed my passion for discovery. I began with Dostoyevsky and proceeded to doggedly gobble up everything from the “Golden Age” of Russian literature I could find in local bookstores. Nineteenth-century Russia seemed like a strange and darkly perverse version of the American Midwest: a huge country with wide rolling rivers, vast tracts of indistinguishable farmland, newish and anonymous cities every few hundred miles, and a bipolar, hostile climate. People were drifting around with a lot on their minds: religious fervor and grand plans for society. How strange it seemed that such outwardly similar places could be governed by personal liberty on the one hand, and autocratic oppression on the other.

I was hooked on Russia.

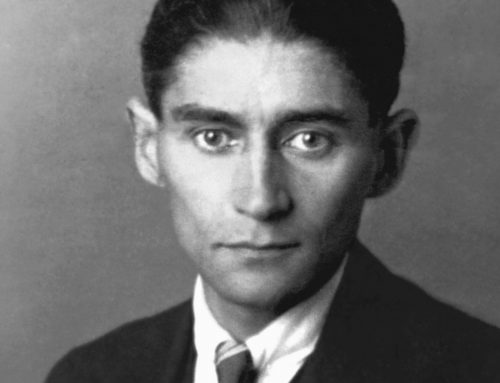

It was Isaac Babel’s Red Calvary that introduced me to Jewish life in the Russian Pale of Settlement. This work of literature has captured my imagination unlike any other. Red Calvary is a snapshot of the Jewish community at a critical impasse: a historical and cultural crossroads. In these stories we see an identity crisis amidst the chaos of war and social revolution in the Russia of that period. Some of the younger Jews join the Bolshevik Party to fight for social change; others struggle to maintain Jewish traditions and values.

A Yefim Ladyzhensky illustration, inspired by Isaac Babel’s story “Gedali in Konarmiia.”

From Babel my interest in Russian literature continued to grow. It wasn’t long before I started to notice that most of my favorite authors had some things in common. Most of them wrote in Russian, were Jewish, came from somewhere in what is today Ukraine, and lived during Soviet rule. Most of these artists made conscious efforts to assimilate into Russian, and later, Soviet culture, but we find similarities between their personal experiences as Jews, and each of them inevitably identified with their Jewish background in different ways.

Many Jewish artists devoted their creative energy to Soviet cultural building initiatives and made major contributions to the project in every artistic medium. However, Soviet political control created restrictions on Jewish themes in the arts. At times, Jewish-Soviet artists relied on the Hebrew Bible as well as secular literature of the Jewish cultural canon as referents to create a coded subtext in their works that would subvert these restrictions. In my research I place these works in their historical contexts, examine the external pressures in a given era that could have been a limiting factor on the expression of Jewish identity, and track the modes of Jewish expression in Soviet literature over the first half of Soviet history. I explore when, why, and how Jewish-Soviet artists incorporate Jewish themes into their works in order to make my hypotheses about the shifting Jewish paradigm in the Soviet Union.

Courses offered in my home department (Slavic Languages & Literatures) have added real depth to my understanding of Eastern European Jewry and provided me with positive momentum to take into what I envision as a dissertation topic. My advisor Professor Galya Diment has played an active role as a mentor in my personal and academic development. Her guidance, support and keen insights have been invaluable to my project. Professor Diment’s Russian Jewish film course (RUSS 423) allowed me to visually apprehend the subject of my study, giving a face to the written material I work with. Instruction I have received from Dr. Barbara Henry has also fostered my interest in Jewish Studies. Her course on Isaak Babel (RUSS 230) was a great benefit to me in refining and conceptualizing parts of my project.

Sketch of Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg by Yuri Annenkov.

My current project for the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship examines the evolutionary processes of art and politics that define the Judeo-Soviet paradigm over the first half of Soviet history, from 1917 (Bolshevik Revolution) to 1953 (the death of Stalin). Over the course of this period, a complex matrix of exigencies forced both Jews and the State to negotiate their positions relative to one another. My study concentrates on the lives and works of the Jewish-Soviet artists Isaac Babel, Eduard Bagritsky, Boris Efimov, Ilya Ehrenburg, Vasily Grossman, Mikhail Koltsov, El Lissitzky, Samuil Marshak, and Mikhail Romm.

As I reflect on where I came from and where I am headed in my academic career, I can see in my mind’s eye the perplexed faces of a few of my closest friends, and I smile. Years ago I too could not have imagined how firmly Jewish-Russian art and culture would take hold of me. The last several years have been transformative, on account of my developing interest in Jewish culture and owing to the experiences I have had by following this interest. I have stood on the cliffs of a Karaite fortress in Crimea, I have stared in anguish at the ravines of Babi Yar in Kiev, and I have mingled with Breslover Chassidim on Rosh Hashanah in Uman. Having grown up knowing next to nothing about Jewish culture, I certainly could not have predicted the role Jewish Studies would play in my life, but I can trace the pages of my favorite books to a basement in Liberty, Missouri, and from there mark the movement in texts that guided me to where I am today.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)