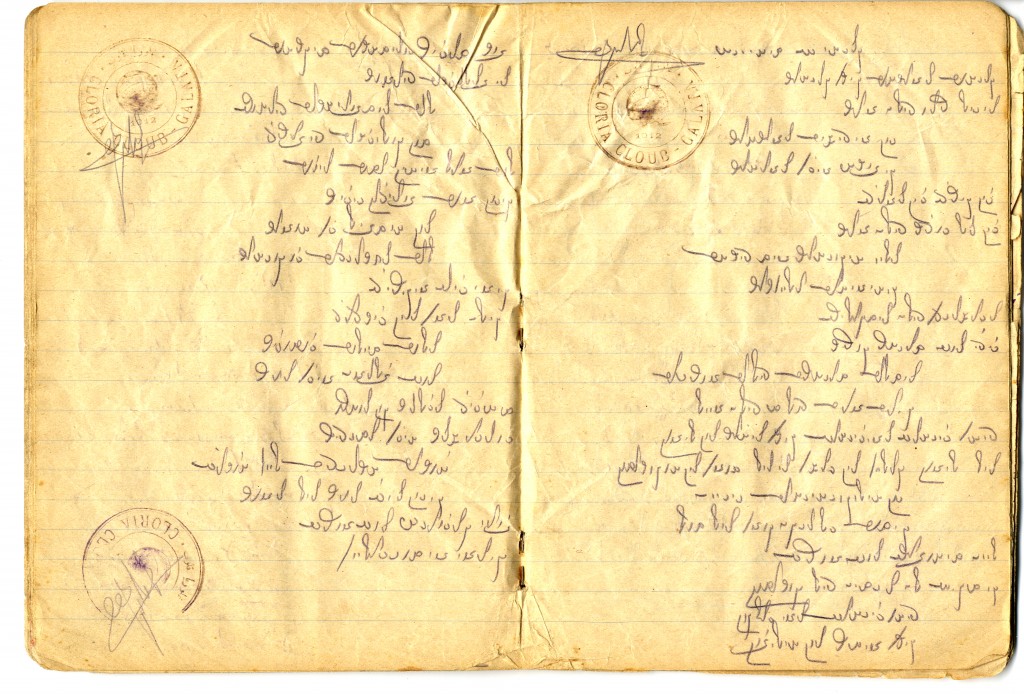

A page of Ladino handwriting from the early twentieth century notebook of Yehuda Leon Behar, a Turkish Jew. Image courtesy of Josie Agoado and Seattle Sephardic Treasures, a project of the UW Sephardic Studies Program.

Do you know any Ladino?

One day in the spring of 2012, I was studying at Suzzallo Library when I ran into Prof. Devin Naar, who had been a guest lecturer in one of my graduate seminars. We took a walk around the UW campus and ended up at Drumheller Fountain, with its stunning view of Mt. Rainier. Prof. Naar, the chair of the Sephardic Studies Program, asked, “Do you know any Ladino?” I said that I had never studied Judeo-Spanish. He replied that it would be easy for me to learn with my background as a native Spanish speaker who had grown up in Mexico and studied Hebrew. That day by the fountain, Prof. Naar happened to have a wedding invitation in his bag, written both in English and Ladino. He handed it to me, and before I knew it, I had started reading Ladino—a language I wasn’t even aware of knowing.

It is hard to describe the feeling of finding yourself reading and understanding a language you have never studied before, seeing how the letters align together and form words and meanings. But if the feeling were close to anything I know, I would call it excitement, curiosity, and joy. In a way, Ladino is Spanish and Hebrew, and having learned both before, being able to read a few phrases in Ladino was not surprising. For me, however, the experience was almost magical.

A few days later I visited Prof. Naar in his Thomson Hall office. He had a diary on his desk and wanted to show it to me. The artifact was from the beginning of the twentieth century and had travelled here all the way from Istanbul. Josie Agoado, daughter of the late Leon Behar, had graciously loaned the manuscript to Seattle Sephardic Treasures, a project of the Sephardic Studies Program. Prof. Naar invited me to have a look at it since it was in Ottoman Turkish, one of the research languages I use in my doctoral research; this was the official language of the Ottoman Empire and was in use from the late fourteenth century until the early twentieth century. The notebook seemed to be written in verse and alternated Ladino and Ottoman. I was instantly intrigued, and together with Prof. Naar, we soon learned that it was not a diary, but the personal notebook of Yehuda Leon Behar, a Jewish officer of the Ottoman army who lived in Istanbul and immigrated to Seattle around the turn of the twentieth century. More importantly, we realized that the notebook was where Behar had documented the entire creative process of poetic composition, by writing, editing, and re-writing the same poem over and over again. In short: the notebook provided an invaluable record of a Sephardic Jewish writer’s literary and linguistic worldview in the early twentieth century.

Language Boundaries

I was born and raised in Mexico City. I learned Spanish and Hebrew when I was a child, and eventually I studied Arabic. I went to the National University of Mexico (UNam) for college and earned a BA degree in History. Since I was interested in Turkish history, I began learning Turkish and moved to London in 2009 to study both Modern and Ottoman Turkish. I lived in Turkey afterwards, and in 2010 I moved to Seattle to pursue my graduate education in the Interdisciplinary PhD program in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at UW. In a way, until I started my project on Yehuda Behar’s diary, Turkish, Ottoman, Persian, and Arabic were my public languages. Spanish and Hebrew, on the other hand, were private and personal. Now, however, these boundaries are no more.

I came to Seattle because I wanted to work with Prof. Selim S. Kuru of the NELC Department, as well as with Profs. Walter Andrews of NELC, Resat Kasaba of the Jackson School, and Joel Walker of the Department of History. My graduate work thus far has focused on Ottoman history and literature, and the history of the Mongol Empires. I have broad research interests including manuscript studies, literary and political languages, and animal-human relations. My dissertation, “Poetry and Politics in the Early Modern Ottoman World: The Court of Bayezid II (r.1481-1512),” focuses on the creation of a new literary language as a mode of political communication in the fifteenth-century Ottoman court.

My Jewish Studies Project: Beyond the Fountain

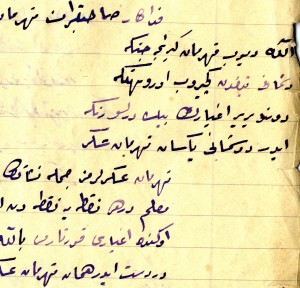

Sample of Ottoman handwriting from the notebook of Yehuda Leon Behar. Image courtesy of Josie Agoado and Seattle Sephardic Treasures, a project of the UW Sephardic Studies Program.

I applied to the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship Program with a project related to the notebook of Yehuda Behar. After two quarters working with Prof. Naar on transcribing and interpreting Behar’s poems, I realized that this notebook was an exciting example of the creative process of poetic composition. The themes explored and depicted in Behar’s poems range from the education of his community—the Jewish community in Istanbul—to the Balkan Wars in the twentieth century. It versifies Behar’s history and personal experiences in creative and literary ways. Moreover, the notebook documents the different stages of composition. Yehuda Behar wrote, edited, corrected, and improved his poems in the notebook’s pages. As the Mickey Sreebney Memorial Scholar for 2013-14, I aim to use the original Ottoman text to reconstruct the ways in which Behar narrated the history of his community, his nation, and his own life.

That day by the fountain, when I read my first words in Ladino with Prof. Naar, I also began a fascinating journey combining different aspects of my life that I had considered independent from each other until that point. The singularity of this notebook and the range of themes Behar explored make this an excellent example of the multilingual and multicultural wealth of Jewish history and culture. The Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship offers me the possibility of sharing the magic I experienced with my first Ladino phrases, a sense of joy and excitement that has only increased as the meaning of these words has become clearer and more familiar to me.

As a grandson of Leon Behar, I am so happy that others are able to enjoy the writings of my grandfather. My mother, who is the only living child, will be thrilled that others are enjoying what she has provided to your program.

YOU DID A GREAT JOB, CONGRATULATIONS.

Delighted to hear about your findings.