By Ke Guo

During one of my many recent Zoom conversations with Hazzan Isaac Azose, cantor emeritus of Seattle’s Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, we revisited an Ottoman tune to a well-known Ladino song.

My research on Sephardic music as a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington has naturally led me to Hazzan Azose, whose parents immigrated to the United States from cities in today’s Turkey, and who is an expert on Ladino and Sephardic music (he also recently celebrated his 90th birthday!). Recently, I asked Hazzan Azose if he knew the popular Ladino song “El Dyo Alto” (alternatively spelled as “El Dio Alto,” which translates to “The God Above”). I then sang for him in the popular melody I had learned from attending events throughout the international Sephardic community.

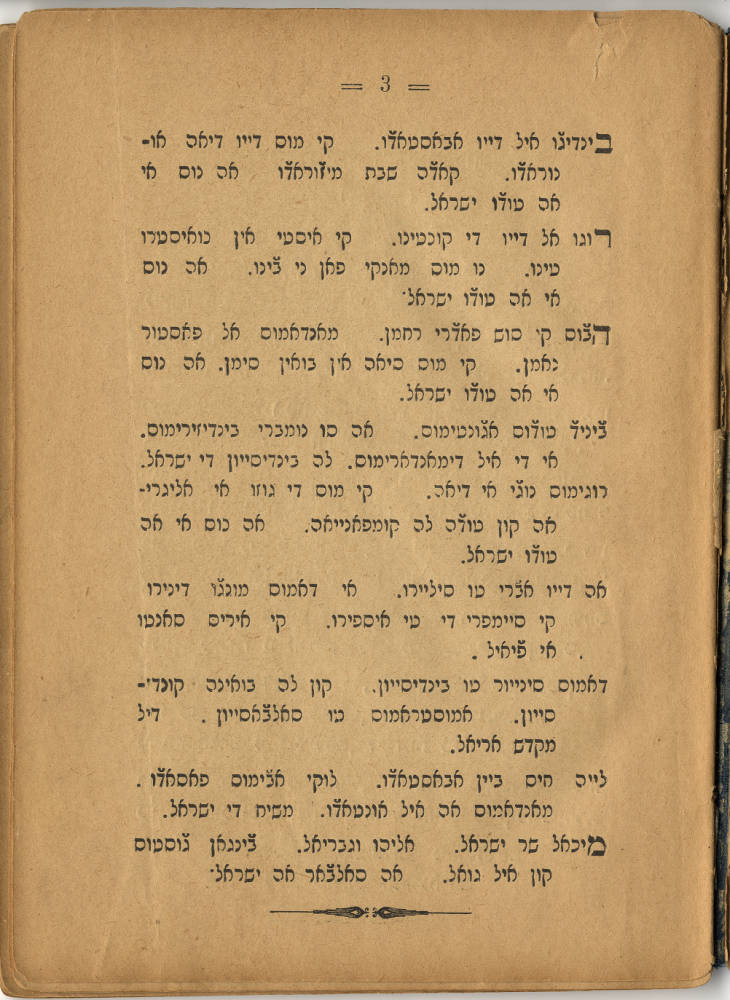

Portion of “El Dyo Alto” (also known as “Kantika de Noche de Alhad” from El bukyeto de romansas. The entire songbook can be viewed online here. (ST0005, courtesy Isaac Azose)

“Oh, I know this song very well,” Hazzan Azose replied, “but I have never heard people singing this song the way you did!” He then proceeded to sing “El Dyo Alto” in the Ottoman style, with long, complex ornamentation in the melody. Although Hazzan Azose claimed that he was not intimately familiar with the Turkish musical system known as makam, the tune he remembered for “El Dyo Alto” certainly had its roots in this Ottoman style.

The melody for “El Dyo Alto” has transformed throughout the centuries. In the Ottoman period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this song was performed in the so-called Turkish musical style, which was heavily influenced by traditional Turkish music recorded by artists such as Haim Effendi (1853-1937).

During the twentieth century when Sephardic Jews moved outward beyond the Ottoman Empire to places in Europe, South America, and the United States, the Ottoman musical style quickly fell out of popularity due to its complex musical system and region-specific aesthetics. In some ways, Seattle was an exception insofar as many of the Ottoman musical styles continued here thanks to the efforts of community leaders, especially figures like Reverend Samuel Benaroya.

In other contexts, artists started to rearrange and re-compose Sephardic songs, adopting eastern artistic music and popular musical styles to facilitate the process of acquisition and transmission in communities.

The currently popular version of “El Dyo Alto,” which has been rearranged and promoted by influential artists such as Judy Frankel (1942-2008) and Rabbi Shuviel Ma’aravi in recent decades, contains an easily memorizable melody in melodic minor scale, without complex melisma (long ornamentation on a single syllable in lyrics), and a triple-metered rhythmic groove.

In El Bukyeto de Romansas, a collection of Ladino songs published in Istanbul in 1926 — and among the very first Ladino books contributed to the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection by none other than Hazzan Azose himself — “El Dyo Alto” is listed under the title “Kantika de Noche de Alhad” and designated with makam huseyni. In various popular versions of this song today, the lyrics contain fewer stanzas, as well as some variation in content, compared to the version printed in El Bukyeto.

In some versions, Hebrew stanzas were added on top of the Ladino text as well. Despite these variances, nearly all versions of “El Dyo Alto” feature the same opening stanza and refrained phrase of the song:

| Transliteration:

El Dyo alto kon su grasia. Mos mande muncha ganansia. No veamos mal ni ansia. [refrain] A nos i a todo Yisrael. |

Translation:

Oh! God on High with grace May He send us much fortune. May we see no evil, nor anxiety. For us and all of Israel. |

In this Zoom recording from one of my recent meetings with Hazzan Azose, (October 28, 2020), he adopted the complete text from El Bukyeto de Romansas and sang it with the melody that he remembered from his youth. With the hope to re-present this song as it was transmitted from the world of the Ottoman Empire to the Pacific Northwest, this recording offers a historical repatriation of “El Dyo Alto,” or “Kantika de Noche de Alhad.”

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

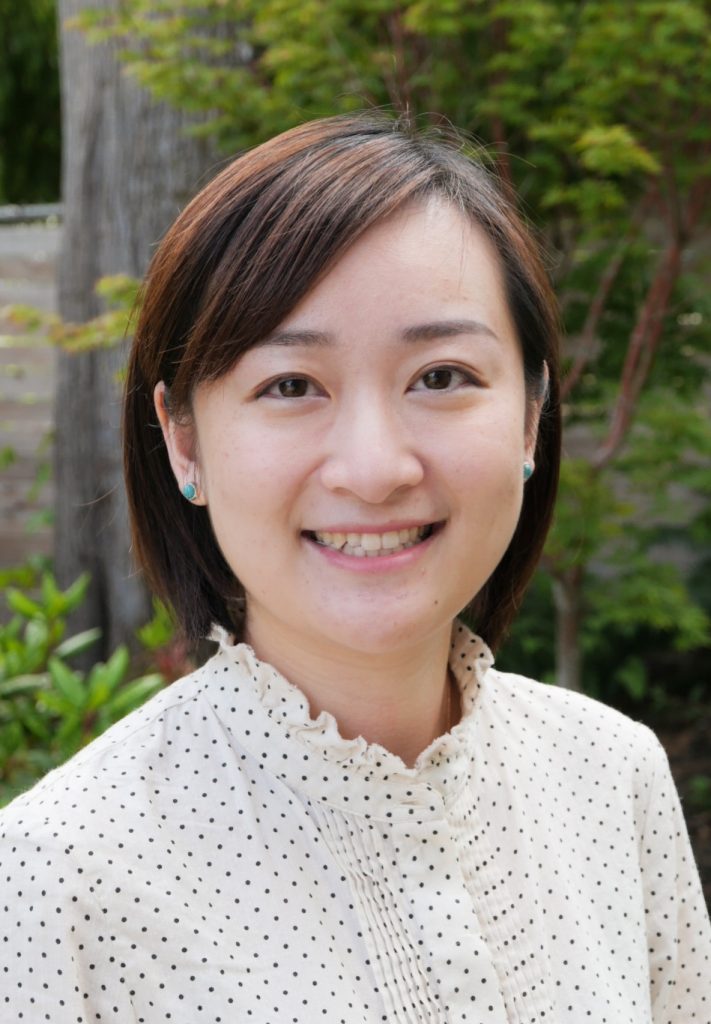

Ke Guo is a Ph.D. student in music education with a focus in ethnomusicology at the University of Washington’s School of Music and the 2020-21 Robinovitch Family Fellow in the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. Her research in world music education and ethnomusicology has covered topics in both Chinese music and Sephardic music. As a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, she is also active as a concert performer, and has offered individual concerts as well as collaborative concerts in America and Europe. Focusing on the topic of the worldwide transmission and reception of Sephardic music both within and outside of the Sephardic community, she is excited to conduct future field research in the Iberian Peninsula, Turkey, and other countries around the Mediterranean.

Ke Guo is a Ph.D. student in music education with a focus in ethnomusicology at the University of Washington’s School of Music and the 2020-21 Robinovitch Family Fellow in the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. Her research in world music education and ethnomusicology has covered topics in both Chinese music and Sephardic music. As a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, she is also active as a concert performer, and has offered individual concerts as well as collaborative concerts in America and Europe. Focusing on the topic of the worldwide transmission and reception of Sephardic music both within and outside of the Sephardic community, she is excited to conduct future field research in the Iberian Peninsula, Turkey, and other countries around the Mediterranean.

If musicians were the world leaders, or local rulers–we would never had any wars on this sad planet of ours. All the musicians want to do is to jam together. Ke Guo is one wonderful person!