Hora dancers at Kibbutz Dalia, 1945, Israel. From the National Photo Collection of Israel.

By Sarah Riskind

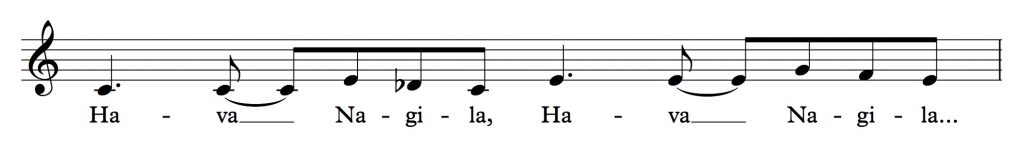

You’re having some nibbles at a wedding or a bat mitzvah, and suddenly the exuberant sound of Hava Nagila reaches your ears. Before you know it, there’s a mob of hora dancers on the floor, and you can’t help but join in.

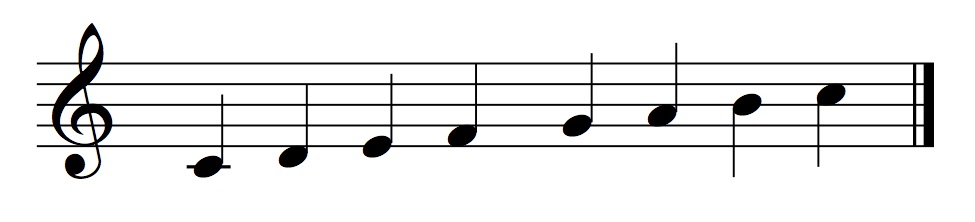

The words “Let’s rejoice and be happy” (“hava nagila”) are about celebration, but a mainstream European or Christian song with the same text would sound quite different. Think of Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” from The Messiah or “If You’re Happy and You Know it.” Those of us raised amidst Western music associate happiness with major keys, or keys that use this set of notes:

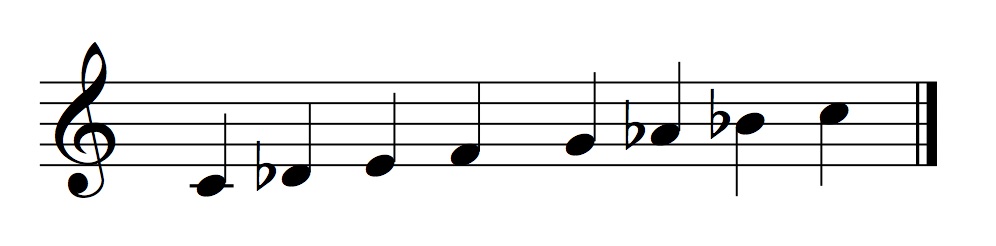

The first part of Hava Nagila uses a scale sometimes called the “Jewish” mode. (A mode is a pattern of steps, like a scale, that informs which notes a song uses and how.) It sounds like this:

In reality, this scale is common in many musical cultures: in Arabic and Ottoman music, North and South Indian classical music, Iranian music, Spanish music, and more. The Yiddish name for it is Freygish, the Hebrew name is Ahava Rabbah, and Western music theory labels include “Phrygian Dominant,” “Harmonic Minor Mode 5,” and more.

Ahava Rabbah shares the most distinguishing feature of the major scale—the interval between the first and third notes of the scale (or the first two notes of Hava Nagila)—but the second note is lower than in major keys (the third note of Hava Nagila). This creates the characteristic interval of the “augmented second.”

In my work on Sephardic music arranged for choir, I have noticed a large number of arrangements in this mode, though I had previously believed it was specific to Ashkenazi musical traditions. These include “Cuando el Rey Nimrod” (When King Nimrod), “Por Que Llorax,” “Blanca Niña” (Why Are You Crying, Fair Maiden), “Hamisha Asar” (Feast of Fruits), “La Rosa Enflorece” (The Rose Blooms), “Nani, Nani” (Lullaby), “Par’o Era Estrellero” (Pharaoh was a Stargazer), and “Si Verias a la Rana” (If You Could See the Frog).

Since most of these songs originated in former Ottoman areas inhabited by Sephardim, we can identify modal influences from the makam system of Ottoman classical music. Many Jewish musicians were involved with Ottoman court music, and their knowledge of makams influenced their liturgical and para-liturgical Jewish music as well.

A makam is more than a scale; it involves certain guidelines for how the melody ascends and descends, how a musical phrase begins and concludes, and more. Some of these makams also use microtones, or notes in between the Western notes that would be found on a piano. The makam family Hicaz includes several makams with similar steps to the Ahava Rabbah scale, though the notes in the “augmented second” are tuned closer together than in Western practice. Listen to this music that uses Hicaz:

“Cuando el Rey Nimrod,” also known as “Avraham Avinu,” is a widely known Sephardic melody that celebrates the birth of Abraham:

When King Nimrod went out into the fields,

and looked up at the heavens and at the stars,

he saw a holy light above the Jewish quarter,

a sign that Abraham our father was about to be born.

Abraham, our father, beloved father, blessed father, light of Israel.

This version comes from the Center of Folklore and Folktales, a project of Dr. Yoel Perez of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Notice that although some moments sound minor, many phrases of the melody start and end on the opening note, which is also the “home” note or tonic of the Ahava Rabbah scale.

I identified “Par’o Era Estrellero” (“Pharaoh was a stargazer”) as an example of the Ahava Rabbah scale because the end of each verse falls on what would be the home note or tonic in Ahava Rabbah, but one could easily hear it as an example of the minor scale that uses the same set of notes. In fact, the arranger Eleanor Epstein repeats the first phrase at the very end of her choral version, which leads the listener to interpret it as a composition in minor.

In other words, instead of the Ahava Rabbah scale, this song could also use the harmonic minor scale that begins on the fourth note:

Listen to “Par’o Era Estrellero” and make your own judgment!

This version comes from choral group Zemer Chai, from the album Same Earth Same Sky.

When a choral composer, or any musician, is adding harmony to a Sephardic melody, the question of mode becomes more than academic. These interpreters make decisions about which notes to emphasize, how to start and end each passage, and which chords to use based on how they classify the mode or key.

The influence of Ottoman and Arabic modes in these melodies adds many more possibilities, including scales with microtonal notes that few Western musicians have trained themselves in singing. In my dissertation on informed and informative choral arrangements of Sephardic music, I have already faced challenging musical decisions in my own original arrangements, and I urge choral arrangers and conductors to be aware of these nuances.

If you walked into a place of worship blindfolded and heard the opening chords of a song, there is a good chance you would know whether or not it was a synagogue. By using scales from both Ashkenazi and Sephardi traditions, composers have been reinventing and revitalizing Jewish music since the nineteenth century. Even with extensive cross-fertilization, unique musical elements deepen the distinctive identities of many religions, especially Judaism.

Love Sephardic music? Learn about, and listen to songs from, our Collection of Sephardic Ballads and Other Lore.

Sarah Riskind, Robinovitch Family Fellow, is a doctoral student in choral conducting in the UW School of Music. Originally from Boston, MA, she holds degrees from Williams College and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In addition to conducting, singing, and teaching, she has composed choral and instrumental works that have been performed in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Washington, many of which use Jewish liturgical texts in Hebrew and English. She is currently pursuing research on choral arrangements of Sephardic Jewish music.

Sarah Riskind, Robinovitch Family Fellow, is a doctoral student in choral conducting in the UW School of Music. Originally from Boston, MA, she holds degrees from Williams College and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In addition to conducting, singing, and teaching, she has composed choral and instrumental works that have been performed in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Washington, many of which use Jewish liturgical texts in Hebrew and English. She is currently pursuing research on choral arrangements of Sephardic Jewish music.

I am so sorry to have missed the concert Wednesday. I loved Sarah Riskind’s detailed post about the scales and modes used in Jewish music and particularly music sung in Ladino. Was the concert recorded? If not, will there be another chance to hear this music any time soon?

Great work, Sarah!

Jonathan Freedman

Hi Jonathan, the University of Washington’s student newspaper has created a writeup of Sarah Riskind’s March 13 lecture/concert that includes a number of audio excerpts of the performances. The article is available here.

Loved to read this. Came across because of an article I am interested in about the Jewish origin of the Chinese new year’s song gongxi gongxi. https://www.dflat.com.my/blog/2019/2/4/in-retrospect-origin-of-chinese-new-year-music. It is not so easy to get the parallel of the Hatikvah (at least for me). So, in your scholar opinion, does gongxi gongxi have the Jewish dominant second? listen e.g. this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sf0btvROwXQ

Very interesting. I’d be interested in discussing this in light of some controversies that have arisen recently regarding the study of music theory and racism. Specifically, I like how you related the music theory to itself internally and did not compare it to how Western music of the 18th century would see it.

Beautiful! I love the rich emotions of harmonic music using Makams.

Some Greek music scales seem similar to Hebrew, too.