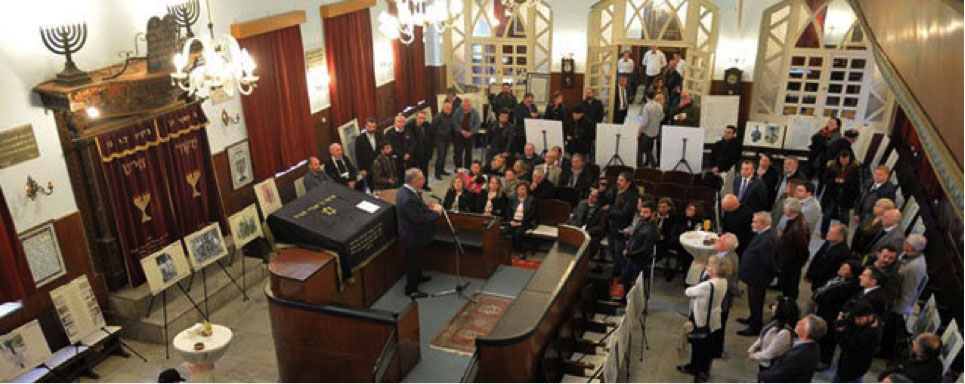

Visitors to the”First World War and Ottoman Jews” exhibit at Mekor Haim Synagogue, Çanakkale, Turkey

By Özgür Özkan

Çanakkale is a small and unique coastal town by the Dardanelles in Turkey that has a vibrant cultural diversity. In the early 20th century, it was home to around 350 Sephardic Jewish families. Today, only three remain.

Despite the significant decline in the Jewish population throughout the 20th century, Çanakkale maintains its Jewish cultural heritage through the remarkable efforts of local institutions, city administration, and its Jewish diaspora, which has dispersed to Turkey, Israel, and other countries, including the United States. Last year I investigated Çanakkale’s Sephardic connections to Seattle.

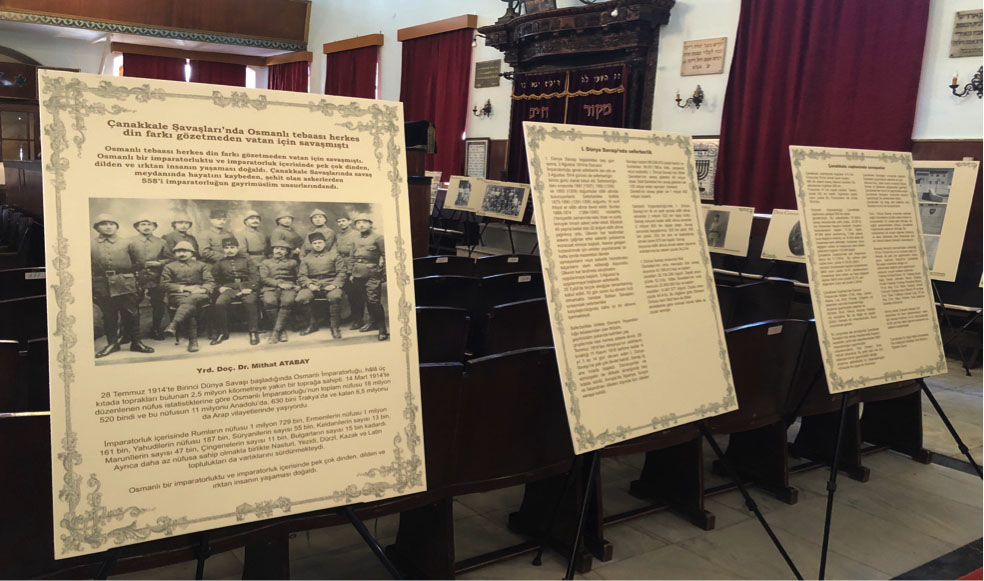

When I visited Çanakkale in March 2018, a very interesting event was being held at the city’s Mekor Haim Synagogue. The event was an exhibit about Sephardic soldiers in the Ottoman army entitled “The First World War and Ottoman Jews.” Organized with the contributions of the 500th Year Foundation of the Turkish Jewish Museum and the local community, the exhibit is another project made possible by the collaborative efforts of local groups.

The exhibit is unique not only for highlighting an underappreciated part of the city’s history, but also for how it reveals the peaceful, inclusive, and countercultural character of the local community. The exhibit demonstrates the city’s long-standing efforts to protect its cosmopolitan identity in the face of Turkey’s intensifying ethnic and religious conservatism and the nationalist narratives regarding itss history.

In Turkish historiography, Çanakkale’s name is almost exclusively associated with the defensive battles that took place along the Dardanelles Strait and around the city during the First World War, where the Turkish armies won a notable victory over invading British forces in 1915.

In spite of this positioning in Turkish history, the local community embraces a different narrative, one which recognizes both the courageous defense mounted by the Turkish army and the sacrifices made by all soldiers, regardless of their ethnicity, religion, or nationality. Emphasizing the city’s long-standing culture of tolerance and coexistence, locals prefer to be remembered as “the city of peace.”

At the ceremony celebrating the opening of the exhibit, the city’s mayor, Mr. Ülgür Gökhan, remembered the friendships he had made with Jewish peers as a student and with fellow Jewish businessmen in Çanakkale’s carşı, or little business district. He reminded listeners of the contributions of Jews to the city: “The Jewish community has been an essential part of the commercial life that has given our city its unique direction. They have made significant contributions, not only to the city’s economy, but also to its culture. If there is a peaceful environment in Çanakkale today — and we call it ‘the city of peace’ — this is a product of a modern and pluralist lifestyle we have long embraced, to which Jewish culture has made significant contributions. We are sad that many Jews left our city.”

The exhibit comprises 66 visual and textual documents, which were put together with the contributions of scholars and Turkey’s Jewish community.

Dr. Mithat Atabay, a professor of history at Çanakkale University, identifies 558 non-Muslim soldiers who fought in the Ottoman army in the Çanakkale/Gallipoli front alongside Muslim soldiers and lost their lives, whose memories the exhibit honors. The exhibit highlights not only the contributions and sacrifices of Jews during the war, but illustrates the real human impact of traumatic events in history and their implications for historical memory.

Memo mentioning Jewish foundations’ support for volunteer Jewish and Muslim soldiers and their families. Source: Başbakanlık (Prime Minister’s Office) Archive

The Jews’ contribution to the Ottoman struggle against the imperialist enemy forces was not limited to joining the ranks of the army. Despite many difficulties, various Jewish foundations and associations offered help to the families of soldiers — both Jewish and Muslim — during and after the war.

The exhibit is composed of five parts:

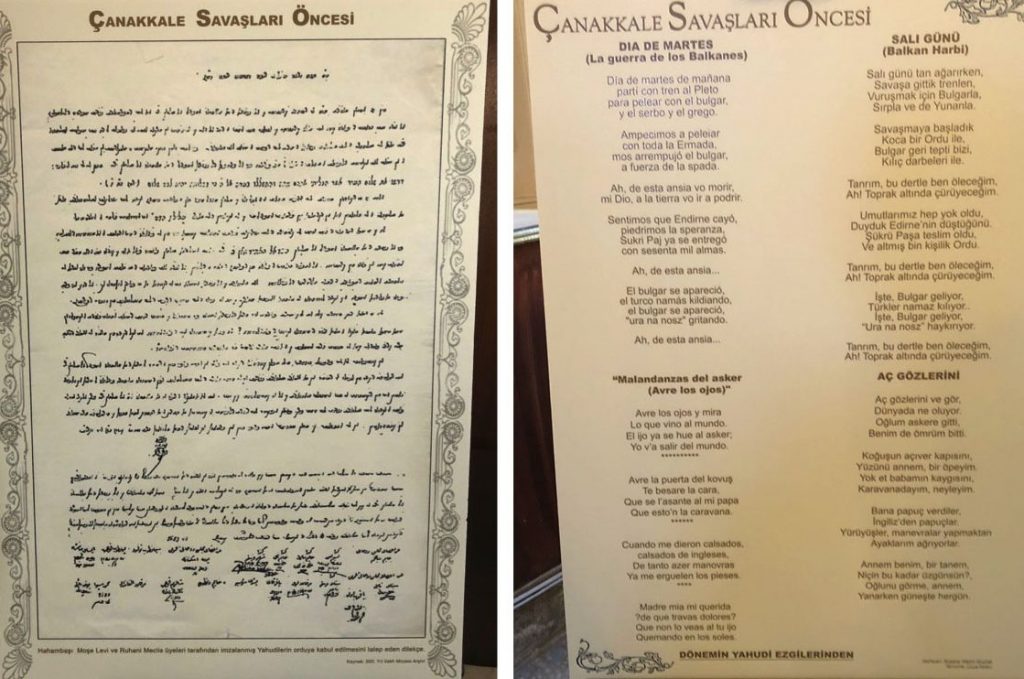

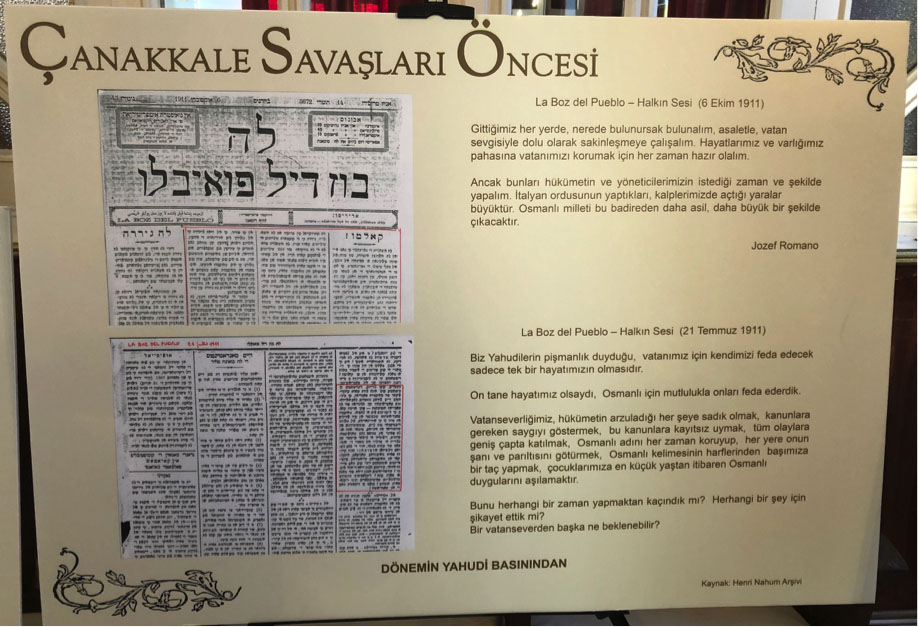

The first section displays a petition to Sultan Abdulhamid II in 1893 that requests that Jews be allowed to serve in the army. Newspaper articles and folk songs expressing the views of the Jewish community regarding war and military service during the Turco-Italian and Balkan Wars between 1911 and 1913 are also displayed.

Left: Letter to Sultan Abdulhamid requesting that Jews be allowed to serve in the army. Source: Archive of the 500th Year Foundation Museum. Right: Examples of Jewish folk songs from the period. Compiled by Susana Weich-Shahak; translated by Coya Delevi

The second section is dedicated exclusively to the battles on the Canakkale front. It highlights Jewish participation and sacrifice on the Ottoman front lines and shares the list of names of those who lost their lives.

The third section recalls the fact that many young German Jews volunteered to serve in the Ottoman army during the Balkan Wars. It showcases foreign Jews’ support for the Ottoman Empire during the existential struggle that took place before its collapse.

The fourth section is titled “Everybody Fought for His Own Patria,” and illustrates an uncomfortable reality of war: sometimes two relatives are pitted against each other as soldiers of two warring countries. In the Balkan Wars and the First World War, many Jews fought against each other in the armies of their countries. Those who shared the same last name had to fire bullets at each other. Many never returned from the fronts they had been deployed to–often places they had never heard of.

Ottoman soldiers. Left: Ottoman Army Officer David Hakohen from Palestine. Source: The Moshe Sharett Heritage Society. Center: Yako Kohen. Source: Jake Kohenak Archive. Right: Lt. Abdullah Abigadol with troops. Source: Archive of the 500th Year Foundation Museum

Master Sergeant Nesim Avram Eskinazi, Canakkale, Anafartalar 1916.

Source: Archive of the 500th Year Foundation Museum

The fifth section is a survey of Jewish soldiers who served in the various fronts of the First World War, from Sarikamis to Çanakkale, Galicia, and Yemen. It includes short memos and photos of notable Sephardic Jewish soldiers who served in the Ottoman Army at the turn of the twentieth century:

Vice-Admiral Ilya Kohen (Imperial and Naval Medical Centers)

Vice-Admiral Isaac Molho (Navy-Medical Inspector General)

Lieutenant General Jak Nisim (Operations Chief-Selanik)

Colonel Ilya Modyano (from Selanik)

Lieutenant Colonel Ishak Levi from Skopje

The “First World War and Ottoman Jews” exhibit is yet another product of collaborative efforts between the local community and its Jewish diaspora, which returns to the city every year in the last week of October to commemorate their former hometown through songs, prayers, and conversations with old friends.

Through efforts like these, Çanakkale, the “City of Peace,” continues to defend its identity as an inclusive city that preserves and celebrates its diverse cultural heritage. In Turkey’s increasingly polarized political atmosphere, this small city’s cultural resistance gives direction to others who are dreaming of a future built on the foundations of peace, tolerance, and coexistence.

Learn more about Özgür’s research on Sephardic soldiers, Çanakkale’s history, and connections between the 20th century Mediterranean and Seattle at his upcoming research presentation on Friday, April 27, 2018.

Özgür Özkan is a PhD candidate in the Jackson School of International Studies’ doctoral program. He holds a BS degree in Systems Engineering and an MA degree in Regional Security Studies from the US Naval Postgraduate School. Özgür’s research covers nationalism, ethnic politics, and civil-military relations in the Middle East. He has been conducting research on non-Muslims’ experiences in the Ottoman Army in the early twentieth century. He is planning to study Sephardic Jewish heritage in the northern Aegean and southern Marmara, especially in Çanakkale and its vicinity, as well as Jewish participation to the Balkan Wars and the First World War.

Özgür Özkan is a PhD candidate in the Jackson School of International Studies’ doctoral program. He holds a BS degree in Systems Engineering and an MA degree in Regional Security Studies from the US Naval Postgraduate School. Özgür’s research covers nationalism, ethnic politics, and civil-military relations in the Middle East. He has been conducting research on non-Muslims’ experiences in the Ottoman Army in the early twentieth century. He is planning to study Sephardic Jewish heritage in the northern Aegean and southern Marmara, especially in Çanakkale and its vicinity, as well as Jewish participation to the Balkan Wars and the First World War.

My grandfather’s picture is in the exhibition. He’s the one in the center holding the rifle with a bayonet (Yako Kohen) of the three picture spread in the article. I am the contributor of the picture, although my name is spelled wrong. I have several copies of the picture, one of which is poster size.

How cool! Thank you for your comment. We’ve corrected the spelling of your name in the photo caption.

Thank you for the correction!! Jake

I read Özgür Özkan articles regarding Çanakkale with great interest. My grandparents and mother immigratedto U.S. in 1912 from Çanakkale. The family name was Eskinazi. My grandfather had a brother named Nesim Eskinazi thus interest in posted picture of Nesim Eskinazi. Is there any way to find additional info on Nesim(family, etc.) and are there any exhibits, etc @the Stroum Center @ the university that are open to the public. We are planning to visit Seattle in July and would appreciate knowing of any place we could visit that might provide more information.

Thank you,

Regina D. Katz

Hi Regina, thanks for your comment. Özgür does most of his research on Çanakkale in Turkey, and unfortunately, the photograph of Nesim Eskinazi is from the collection of 500th Year Foundation Museum of Turkish Jews in Istanbul, Turkey. Here is a link to their website if you’d like more information about this museum.

Here in Seattle, you could try e-mailing or meeting with the University’s Turkish/Jewish materials librarian Mary St. Germain. Here is more info about Mary.

There is a Dr Nesim Eskinazi in Istanbul – who is a famous pediatrician loved by the locals.

Thank you for a fascinating article on Canakkale. My mother and her family (Asriel or Azriel) were originally from Canakkale, later moved to Salonika where they survived the Great Fire of 1917 before emigrating to New York in 1920.

My dad (Joseph Gabay/Yoseph Gabai) was from Edirne. As a teenager, he served as a truck driver in the Turkish army during WW I. The earliest photo I have of him, and one that I treasure dearly, is one taken of him in his army uniform.

Thanks for your article. My grandparents Saltiel Leal and Palomba Aldoroty were born in Canakkale and emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s. My grandmother’s brother David Aldoroty was a Turkish soldier killed at the battle of Gallipoli.

Esther Eskenazi Benezra to Regina Katz

My grandfather was Nessim Yusuf Eskenazi but he emigrated from Istanbul Turkey in approximately 1916 and actually went to Seattle Wa. Because he had relatives there and he lived in the back of their candy store. Four years later when my father Samuel found him they went back to NYC and lived on the lower East Side when my Nona came with her three more children, David, Rebecca and Issac to be with them. I have no other background info.