Hazzan Ike Azose greets Regina Amira and Jack Altabef, members of “Los Ladineros.”

A Celebration 500 Years in the Making

On December 5th, the University of Washington and the city of Seattle joined communities around the world in celebrating the first ever International Ladino Day, a celebration the Sephardic community has been awaiting for more than 500 years. Over 300 people from the Sephardic and university communities gathered at the University of Washington Hillel to hear stories, songs, and short lectures about Ladino and Sephardic culture.

Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, is the language that developed when the Jews who were exiled from Spain in 1492 relocated to various parts of the world, particularly the Ottoman Empire and North Africa, and integrated elements of the local languages into the Spanish they had taken with them into exile. Ladino, therefore, is a hybrid language that represents not only the Iberian origins of the Sephardic Jews, but also their ability to thrive during their 500-year exile. It is not only a spoken language, but also a language of tremendous cultural importance.

The first Sephardic immigrants to Seattle brought Ladino with them at the turn of the 20th century, but, although Seattle now boasts one of the largest Sephardic communities in the United States, Ladino is a language very much in danger of extinction here and around the world. Since there is really only one generation of native speakers left worldwide, Ladino will cease to be a spoken language in the near future, and so it is critical to preserve the language now while a speech community still exists. The first International Ladino Day was called for by the Israeli National Authority for Ladino in an effort to celebrate Ladino as not only a historical Jewish language, but also a living language still being spoken around the world.

I am not Sephardic; I am not even Jewish, and yet the first ever International Ladino Day was very meaningful for me, not only academically, but personally as well. I am a graduate student in Hispanic Studies, and, though I only “discovered” Ladino earlier this year, I quickly recognized the uniqueness of Ladino, only to be disappointed by the realization that it was a dying language with little hope of revival. I thus decided to use my thesis work to contribute to the preservation of the Seattle dialect of Ladino.

Working with Professor Devin Naar, Chair of the Sephardic Studies Program, and Ty Alhadeff, the new Sephardic Studies coordinator, along with various members of the Sephardic community to organize the event, I had a specific vision in mind: to bring together people from diverse backgrounds to celebrate their different experiences with Ladino while also educating those who, like me just a few months ago, were unaware of the existence of Ladino or its speech community here in Seattle.

The evening began with a welcome from Professor Naar, who praised the collaborative efforts of the community in putting the event together and thanked the sponsors of the event, the Sephardic Studies Program of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, the Division of Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington, and Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, Sephardic Bikur Holim, and the Seattle Sephardic Brotherhood.

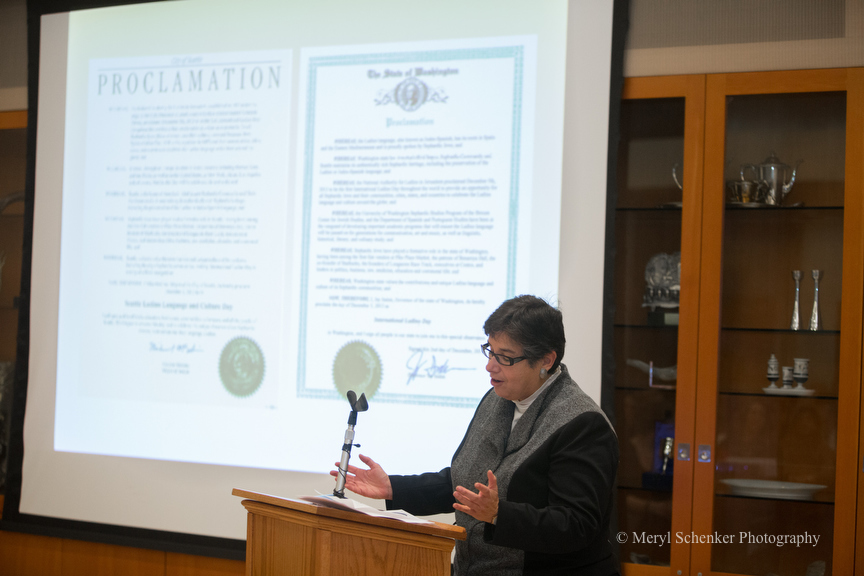

UW’s Provost, Ana Mari Cauce, reading the mayor’s proclamation on International Ladino Day.

Professor Naar’s welcome was followed by the reading of two important proclamations recognizing the importance of the day. Ana Mari Cauce, Provost of the University of Washington, read a proclamation from Mayor Mike McGinn declaring December 5, 2013 Seattle Ladino Language and Culture Day. Former State Representative Marcie Maxwell, Governor Jay Inslee’s senior education policy advisor, then read a proclamation from Governor Inslee declaring the day International Ladino Day throughout the state of Washington. The proclamations were followed by two equally important video messages to the Seattle community, one from Yitzhak Navon, the fifth President of Israel and the current President of the National Authority for Ladino, and the other from Rachel Amado Bortnick, the founder of the online forum Ladinokomunita.

The celebration consisted of a series of presentations, starting with a conversation group that meets weekly in the Central District to practice Ladino and talk about their experiences growing up with the language. “Los Ladineros,” as they call themselves, were led by Hazzan Isaac Azose and sang two songs in Ladino, “Ocho kandelikas” and “Avrij mi galanika,” and then presented the beginning of the history of the Seattle Sephardic community, telling the story of not only their own parents and grandparents, but also the parents and grandparents of many members of the audience.

Los Ladineros perform a special Ladino song in honor of Hanukkah.

Los Ladineros were followed by two presentations by University of Washington faculty, Ana Gómez-Bravo and Suzanne Petersen, both professors in the Division of Spanish and Portuguese Studies. Professor Gómez-Bravo presented some of the converso Sem Tob de Carrión’s proverbs, and Professor Petersen spoke about the Sephardic ballad Flores y blancaflor. Next was Al Maimon, who spoke about a siddur (Jewish prayer book) with a Hanukkah message written in Hebrew and Ladino and published in Belgrade in 1904.

Carolyn Kessler presented a hilarious Joha story in memory of her mother, Lenora Peha LaMarche, who was a well-known Ladino scholar and storyteller in Seattle. Lela Abravanel, a native of Salonica, garnered many laughs with her refranes, or Ladino proverbs, that she has collected over the years. Undergraduate Ladino student Ashley Bobman (profiled in this 2013 article) presented an original poem, called “Muestra kultura,” or “Our Culture.” Ashley’s great-grandfather, Albert Levy, was a well-known teacher in the Seattle Sephardic community whom many members of the community remember fondly. Ashley has been working to translate her great-grandfather’s writings, and wrote her poem about the history of the Sephardim. The celebration concluded with two songs, “El Dio Alto” and “Arvoles,” performed by Hazzan Frank Varon.

The evening provided a fantastic showcase of the historical development of Ladino and its usage today in Seattle and around the world. Through the collaboration of Jews and non-Jews, Ladino speakers and scholars, young and old, we were able to draw attention to this critically endangered but culturally invaluable language. Though scholars have deemed Ladino a moribund language, it is clear to me after this celebration that Seattle has no intention of forgetting about it any time soon.

Molly FitzMorris is a graduate student in the Division of Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington. She has been studying Ladino with the Ladineros for the past six months and is currently writing her master’s thesis about Ladino and the Seattle Sephardic community.

Molly FitzMorris is a graduate student in the Division of Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington. She has been studying Ladino with the Ladineros for the past six months and is currently writing her master’s thesis about Ladino and the Seattle Sephardic community.