Pianist Renan Koen performed a piece by Viktor Ullman, a concentration camp prisoner, at the Terezin Cultural House in 2018. She will be the featured performer at this year’s International Rhodes/Cos Holocaust Memorial.

By Hannah S. Pressman

Being able to play music “is a miraculous way to live,” says the Turkish Jewish pianist Renan Koen.

An accomplished musician, vocalist, composer, and music therapist, Koen has spent the last several years researching and performing works composed by Jews who were imprisoned in concentration camps during World War II. Her quest has led her to a concert at the site of Theresienstadt, the notorious ghetto in Czechoslovakia that served as a propaganda tool for the Third Reich. The research process has also yielded an album, “Holocaust Remembrance ‘Before Sleep,’” highlighting works by composers like Gideon Klein and Viktor Ullmann.

Koen’s purpose is to spread awareness of “positive resistance,” her term for these composers’ ability to create art in the harshest of circumstances. She has established two connected educational programs, “Positive Resistance Through Holocaust Reality” and “March of the Music,” aimed at teaching the younger generation about this history and empowering them to create their own compositions. Koen has organized groundbreaking concerts in Turkey to raise awareness of Holocaust history and the musical legacy of Jewish prisoners. Most recently, she performed this repertoire at the United Nations, where she performed for Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 28th of this year, as well as the U.S. Congress.

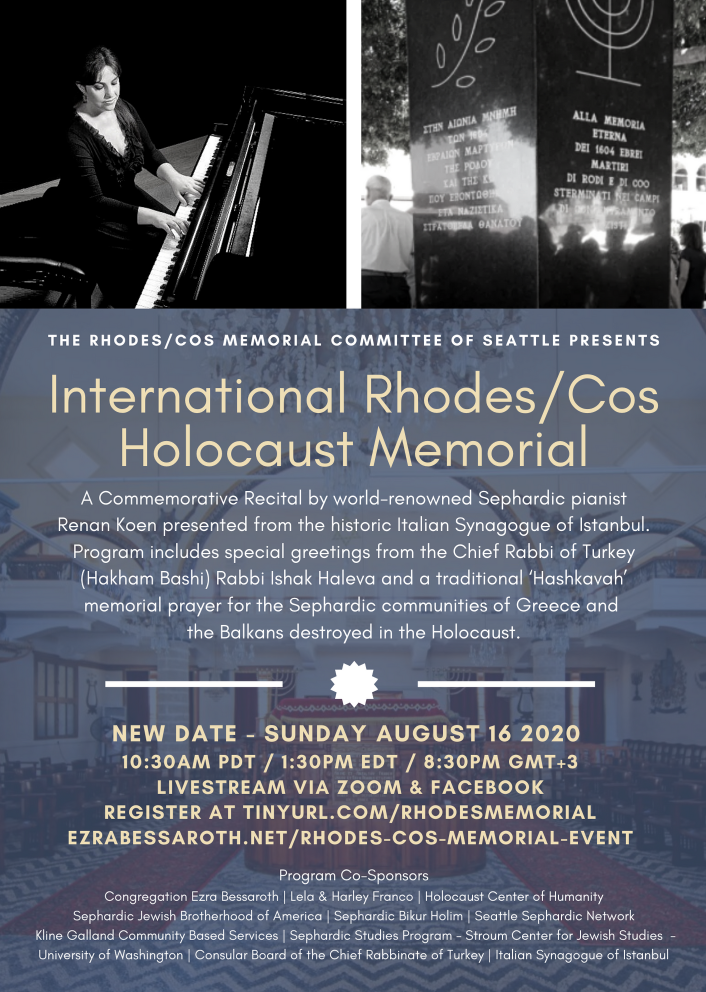

On August 16th, Koen will be the featured performer at the International Rhodes/Cos Holocaust Memorial. (The UW Sephardic Studies Program is a co-sponsor, and Professor Devin Naar is on the event’s advisory committee.) In late July of 1944, close to 1800 Jews from Rhodes and the nearby island of Cos were deported, taken to Greece by boat, and eventually put on trains to Auschwitz. Only 151 Jews from Rhodes survived. As Professor Aron Rodrigue suggested in a 2013 lecture on Holocaust memory, commemorating this catastrophe has become a collective purpose for Rhodesli Jews in Seattle and around the world who have been living in diaspora from “La Chica Jerusalem” for generations.

For the last ten years the Rhodes/Cos memorial has been held at Seattle’s historic Ezra Bessaroth synagogue, founded in the early twentieth century by Jewish immigrants from Rhodes. The synagogue’s patio includes a replica of the six-sided monument to the Holocaust located in Rhodes’ Square of the Jewish Martyrs; the patio’s construction was sponsored by Harley and Lela Franco in partnership with Joel Benoliel, all of whom support the UW Sephardic Studies Program. This year the memorial will be presented virtually, allowing people from around the world to participate. Reflecting this new global reach, the event will include greetings from the Chief Rabbi of Turkey, Ishak Haleva.

Another significant change lies in the date of the event. In past years, Seattle’s memorial event has been held on or close to the date of deportation, July 23rd, which is when the Jewish community of Rhodes typically plans its Holocaust commemorations. This year, the memorial will be on August 16th, which is the historic date that the Jews of Rhodes and Cos arrived at Auschwitz. The program will include a traditional Sephardic Hashkavah memorial prayer for the Sephardic communities that were destroyed in the Holocaust. Hazzan Isaac Azose will also contribute a Ladino song performance.

I recently sat down to have a Zoom conversation with Renan Koen about her involvement in the upcoming Rhodes/Cos Memorial. We spoke about her Sephardic roots, career evolution, and passion for educating young people. We also discussed the emotional toll of making art connected with the Holocaust. When we spoke it was early morning in Seattle and early evening in Istanbul. The following is a lightly edited and condensed version of our conversation and includes a clip from our recorded interview.

Hannah Pressman: Tell me a little about yourself: where you grew up, where you did your musical training, and how you got to this point.

Renan Koen: I was born in Ankara because my family was there for business reasons. We came back to Istanbul when I was three months old. Both sides are Sephardic families. My father’s family comes from Kastoria [city in the region of Macedonia, northern Greece]. We suspect my mother is also – her maiden surname is Kasotoriano, which means from Kastoria! My grandfather’s father was a rabbi and hazzan [cantor] in the Kastoria synagogue.

I started my musical education with flute when I was eight years old. Then when I was eleven years old, I started to have piano lessons at the conservatory. (Now the system is different, but in my time we had primary school, middle school, and the lycée.) After the first year they kicked me out! So we found a new teacher, made corrections in technique, and made huge progress as well. I was still having flute and piano lessons, but had already chosen piano. At the end of middle school, I ended up in Paris with my mother and continued my studies there. To me, it was a very lucky point that they kicked me out because that’s how I found the right teachers, and that’s why I chose piano.

HP: Like the Turkish word kismet [destiny or fate]?

RK: Stronger than kismet, but yes.

HP: So you switched from flute to piano, but at some point also started vocal training, right?

RK: Years afterwards — eight years ago.

HP: I was curious to know, did you hear Ladino growing up, either at home or in your community? Was that something in the environment, or did you have to learn it later?

RK: Well, I’ve never learned Ladino to be honest, but when I hear it, I understand. In my grandparents’ house on my mother’s side, they always spoke Ladino. Everyone was speaking Ladino, but not with our generation. Citizens were encouraged to speak Turkish.

HP: In the work that you do on Sephardic folksongs and Ladino songs, is part of your goal to preserve the language or to help people understand it better?

RK: Of course!

HP: Now to your discography. I have sampled tracks from your albums and I’d love to hear more about your 2014 album, “Lost Traces Hidden Memories.” You refer directly to Rhodes on some of the tracks: “Durme Durme Ermoza Donzeya,” “Tres Ijas Tiene el Buen Rey,” and “Komo la Rosa en la Guerta.” They’re such beautiful songs – so haunting and sad. I was curious about them because my great-grandmother grew up on Rhodes. Can you tell me a little more about those songs and what role Rhodes has in this picture you’re painting? Did you have family there?

RK: No, I had family in Kastoria, but Kastoria doesn’t have any Sephardic songs, at least none that I could find. As you know, there are many connections between Rhodes, Bodrum, and the Aegean side. I felt very close to Rhodes.

View of Kastoria, home of Koen’s family. Source: Trezoros.

HP: How did you pick those songs specifically? Were they ones you had heard?

RK: I researched for months. I have a very good source: Alberto Hemsi, a Sephardic composer [born in Kasaba, Turkey] who collected Sephardic songs from the Ottoman lands in his books. I played and sang through all the songs in his books, and from there I selected the songs to record. [Author’s note: readers can visit the Benmayor Collection of Eastern Sephardic Ballads and Other Lore, part of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection at UW Libraries, to access rare audio recordings of some of the songs collected by Hemsi, including “Durme Durme” and “Komo la Rosa.”]

HP: I have a related question about your role as a composer. I noticed that you adapt songs from different traditions — you have adapted synagogue songs, anonymous folksongs, lullabies. Is this an intentional move to bring these folk traditions, music “of the people,” into what’s called “high” classical music? Are you trying to mix these different types of music into the classical repertoire, which is your training?

RK: All music has life texture behind it. I am very keen on folk music, which has many things to say. Synagogue songs have many things to share — history, background. There is a really delicate intimacy there. That’s why I wanted to bring all of this music to the classical forms and the classical world.

When I examine a new composer, for example, if I wanted to play Brahms, a German composer who lived in Vienna, or Janáček, a Czech composer, if I want to understand these composers more deeply, I start to research the folk music first. I want to know what kind of environment they were living in when they were growing up, what was the feeling when they were out in the street. That tells me a lot.

HP: I think it’s wonderful to challenge the canon a little bit and give legitimacy to these more popular or “domestic” songs, especially from cultures like Sephardic or Yiddish culture. It brings these songs to a new audience.

RK: Thank you.

HP: Now let’s shift and talk about your work with Holocaust music. Tell me about how you got involved with this repertoire, music composed during the Holocaust by imprisoned composers. Does being based in Turkey give you a particular perspective on that history?

RK: As a Jewish person, I grew up with Holocaust knowledge, of course. At a conference I attended years ago, I heard about Theresienstadt, that they [Jewish prisoners] were producing and giving concerts there. I was so curious to know more about the composers and their music. From that point on, I started my research. I quickly learned the composers’ names and their compositions, but the scores are very hard to access. Then one day, in 2011, two scores arrived in my mailbox. It was like a miracle.

Over the next four years, I collected more scores. Then in 2015, we decided to do a bigger event. I worked with someone from the Jewish community and someone from the wider non-Jewish Turkish community, to create the first big event (aside from the official one in Ankara) featuring Holocaust music for a non-Jewish audience. About 750 people attended. Gottfried Wagner, Richard Wagner’s great-grandson, came to this event and spoke. He gave me lots of helpful information about Theresienstadt. [Editor’s note: While the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner was a notorious anti-Semite, his great-grandson Gottfried has been very critical of his forebearer and actively involved in promoting awareness of Jewish history, German history, and Holocaust commemoration, including through music.]

After that concert, I wrote a program for young people, combining Holocaust education and music. I called it “Positive Resistance through Holocaust Reality.”

HP: Is that separate from the March of Music project that you founded?

RK: March of the Music is a continuation. The students in the “Positive Resistance” program had such enthusiasm that I thought I should bring them to Theresienstadt. I also wanted to hold a concert there. In 2018 I took students there and held a concert. I told the students, “This trip has a goal. You need to produce something afterwards — it could be a musical piece, an article, a performance, and I will support you.” One student is a violinist and he established his own trio. Before the pandemic, they would come to my house and rehearse every Friday afternoon. It was so beautiful.

HP: I am sure it is so gratifying to be able to teach the next generation. On that note, why don’t you tell me a little more about the performance program you have planned for the Rhodes/Cos memorial in August?

RK: I talked with the chair of the planning committee, David Behar, to come up with a program. We decided that I would play Gideon Klein’s piano sonata and also Sephardic songs from Rhodes. I am also going to play “Arvoles Yoran Por Luvya,” a Middle Eastern Sephardic song. The Jews who were deported from Salonika sang this song to each other in Auschwitz, so it is very meaningful.

HP: Were there any Sephardic composers in the camps? I know there were Ladino poets and writers.

RK: I have never found any [Sephardic classical composers]. There was one Jewish man deported from Salonika who returned to Salonika (after the civil war), and he composed something as a memoir. I am working on acquiring the composition. [Editor’s note: For a closer look at Sephardic creative expression during the Holocaust, see Isaac Jack Lévy, And the World Stood Silent: Sephardic Poetry of the Holocaust. The volume includes a song by Seattle’s Jennie Adatto Taraboulos.]

HP: So as of now, the repertoire is primarily Eastern European composers.

RK: Yes.

HP: It sounds like an amazing program. I also saw that you will be playing in the Italian Synagogue of Istanbul.

RK: Yes. It’s a very old synagogue in Istanbul. It was built in the 19th century. We had an Italian community here from the Ottoman Empire period. They came from Italy for business purposes, because the sultan asked them to come for trade. They have their own community, under the umbrella of the chief rabbinate of Turkey. They all speak Italian, Turkish, and Ladino — it is an amazing, amazing community. [Editor’s note: The Italian synagogue was home of the Maftirim, a special genre of Hebrew sacred music sung in the Ottoman style. Dr. Maureen Jackson, former Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center, wrote the award-winning book Mixing Musics about the Maftirim. You can view Hannah Pressman’s 2014 interview with Dr. Jackson at this link.]

Interior of Kal de los Frankos, the Italian synagogue in Istanbul. Source: Turk Yahudileri.

The synagogue is very nice. They have a harmonium [small organ] there which they recently repaired. I took some lessons with a priest to learn how to play it, and started giving harmonium concerts in the synagogue. The president of the Italian community in Istanbul asked me to play more concerts, and we brought in more instruments. Now, the Italian Synagogue is part of the Istanbul Music Festival! I’m very proud of that.

HP: The Rhodes/Cos Memorial usually takes place at Ezra Bessaroth Synagogue, which was founded in Seattle by Jews from Rhodes. This year, everyone’s apart but coming together online to commemorate. What does it mean to you to be part of the first virtual memorial event for this community?

RK: It means a lot to me, of course. Each time that I give these Holocaust concerts — with Sephardic songs, Theresienstadt composers, or music from the Warsaw Ghetto — I always feel deeply touched. As for Rhodes and the Seattle community, I have never been to Seattle, but I know Sam Amiel. I find Seattle’s Sephardic community very interesting because I know many people came from Turkey and from Greece, so I am very interested and very curious to know more. It touches me in many different ways, really.

HP: I know that this kind of work takes a lot of research and a lot of time. It’s also emotionally demanding. My great-great-grandmother Rivca was deported from Rhodes and died the day she arrived in Auschwitz. My motivation to work on this is in her honor; whenever I write about it, it’s very difficult. I’m sure that when you play these pieces, it’s very hard. But it’s so important, and it means so much that you have this gift that you can share.

RK: It is very hard, but I don’t derive as much satisfaction from anything else I do. Other aspects of my work, like being a music therapist and working with individuals or groups, are also very meaningful for me. But this work on the Holocaust — well, I don’t name it as work. It’s something very different that I cannot describe with words really.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Further reading:

- Aron Rodrigue – Sephardi Jewries and the Holocaust (Video of Stroum Lecture Series, 2005)

- Devin Naar – Sephardic Jews and the Holocaust: In Search of Uncle Salomon (Video of JewDub Talks, 2012)

- Hannah Pressman – Remembering Rhodes, Family History, and the Sephardic Holocaust (August 2014)

- Berkay Gulen – “Close to My Ancestors”–The Restored Grand Synagogue of Edirne, Turkey (March 2016)

Dr. Hannah Pressman writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming in 2021). She is currently at work on Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey, a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Dr. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Dr. Hannah Pressman writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming in 2021). She is currently at work on Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey, a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Dr. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Thank you for keeping our heritage alive.