Seattle’s long-time Ladino-speaking group, Los Ladineros, perform at Ladino Day 2018.

By Makena Mezistrano

This year’s International Ladino Day began on the afternoon of December 5th, prior to anyone taking the stage in Kane Hall on the University of Washington’s campus later that evening. For me and eight other graduate students and professionals, it began over lunch with this year’s keynote speaker, who was, for the first time, an international guest. An award-winning publisher, cultural activist, and the vice president of Aki Estamos – Les Amis de la Lettre Sépharade, a Paris-based organization dedicated to the Judeo-Spanish language and culture, François Azar previewed his motivations for his endeavors and his passion for Judeo-Spanish.

Francois Azar, the featured speaker at this year’s Ladino Day, promotes Judeo-Spanish in France.

Contrary to the trend these days to refer to the renewed international interest in Ladino as a “revival,” Azar instead insists that his goal is “transmission.” Rather than revive a language that has already been lost as an everyday language, he wants to bridge the gaps between generations and communities. Since members of the older generations are still with us and able to speak in the vernacular, Azar views his work as a way to connect that last generation of native or semi-native speakers with the less acquainted younger generations. He also wants to bring Ladino beyond the realm of the Sephardic world and make it resonate for people with more varied cultural identities.

That universalizing impetus was on display at the lunch. The attendees had diverse personal and intellectual backgrounds in Ottoman and Turkish history, French literature, Spanish history, Middle Eastern studies, and Sephardic studies. The geographic, cultural, and disciplinary interests of the group made it apparent to all of us how far-reaching the appeal of Judeo-Spanish culture is on campus, and the extent to which Azar’s observation — that Ladino is poised to be embraced widely —is on target.

Azar specifically focuses his efforts not only on disseminating knowledge about Ladino, but more importantly, creating content in Ladino. He seeks to give Ladino a platform in modes and mediums able to be enjoyed by all ages, and among Jews and non-Jews. His modes of transmission include an intensive summer school, a magazine, cooking classes, musical performances and recordings, dances, and children’s books.

Azar gave each of us at the lunch a copy of “Djoyas de Mar,” the album of Ladino and Greek songs he produced for the Greek singer Dafné Kritharas, who is of part-Jewish background. Azar described his collaboration with musicians and singers with family roots in the world of the former Ottoman Empire — not only Sephardic Jews, but also Greeks, Armenians, Turks, Kurds, and more—as key to bringing Ladino culture out into the public, and framed within the context of world music. Through the music, he seeks to recreate the lost world of the cosmopolitan Levant.

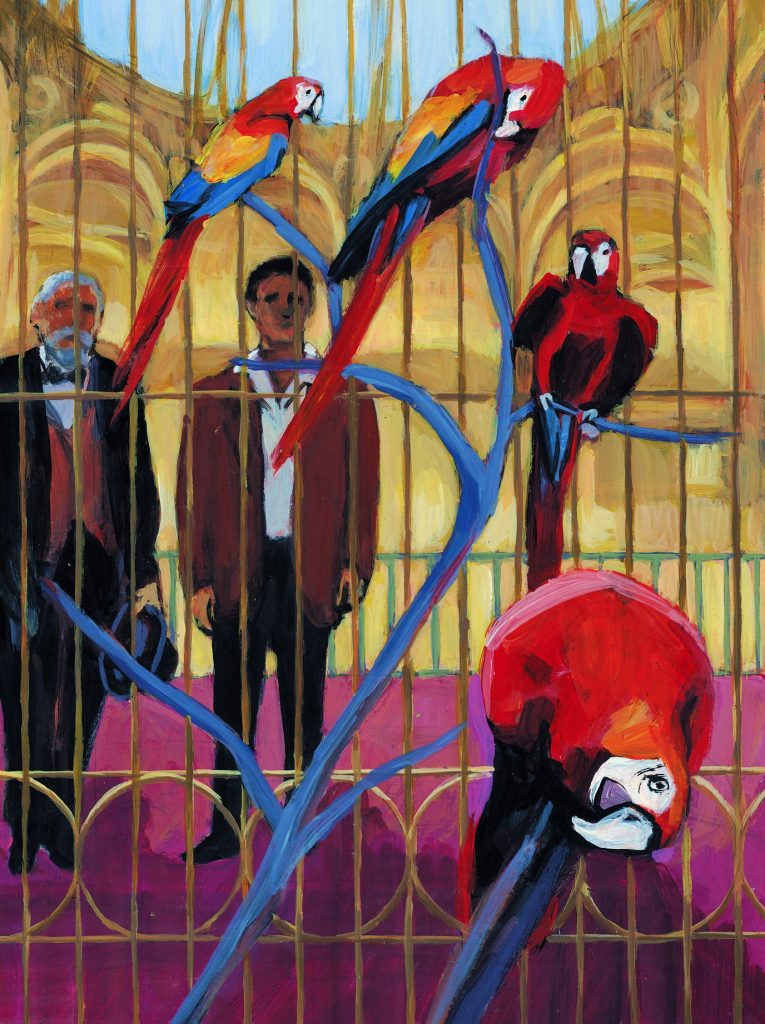

One of the darker images from Azar’s ‘Bewitched by Solika,’ illustrated by Petros Bouloubasis (2016).

Azar was not invited to focus on music, however fascinating that work may be. Instead, his focus was on folktales. Passing two of Azar’s illustrated folktales around the lunch table, we commented on the beauty of the artwork in each, noting the vibrant illustrations in El Papagayo Djudyo (The Jewish Parrot, 2014) compared to the darker drawings in Bewitched by Solika (2016). Azar speculated on this variance: Petros Bouloubasis, the award-winning, Athens-based illustrator of Bewitched by Solika, illustrated the book during Greece’s precipitous economic decline, and the collective mood in Greece likely influenced his artwork.

Having first enjoyed previous Ladino Days as a virtual audience member from New York watching my grandmother, Lela Abravanel, perform her beloved refranes (proverbs), to serving on a panel myself two years ago, I was thrilled to have the chance to engage with this year’s Ladino Day keynote speaker in a more intimate setting and get a sneak peek for the evening’s program.

Audience members enjoying the Ladino Day 2018 performance.

Later that night, a crowd of more than 250 attendees gathered in Kane Hall for the formal Ladino Day Program, “Jewish Folktales from the Mediterranean.” Following opening remarks by Noam Pianko, Director of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, and Devin Naar, the Isaac Alhadeff Professor of Sephardic Studies, François Azar set the audience up for an unforgettable performance: a reading of one his stories, The Jewish Parrot, by Seattle’s Judeo-Spanish interest group, the Ladineros.

The Ladineros are a group of community members who gather weekly at the Summit, a Jewish retirement community in Capitol Hill, to reminisce and read and chat in and about Ladino. The group’s performance was a memorable highlight of the evening as they performed their rendition of Azar’s El Papagayo Djudyo in Ladino. A slideshow behind them provided translations for the audience, and also featured some of the colorful illustrations from the book. As two members of the Ladineros narrated the scenes, six others took on character roles. Each of the Ladineros offered a lively performance; all were expressive, and appeared to truly enjoy taking on their respective character roles. A highlight was Al Shemarya’s rendition of Ahot Ketana as he sat on stage with a parrot hat atop his head.

Watch the Ladineros perform “The Jewish Parrot”:

Following the Ladineros’ performance, Azar later explained in his lecture that folktales such as the Jewish Parrot must not remain static texts, but rather be treated as living stories to be reimagined by those who tell and retell them. Although he changed the medium of the traditionally oral folktale by writing it down, Azar said that it is important for the stories to retain fluidity and inspire creativity among readers and re-tellers. This also speaks to Azar’s larger point about folktales: through this oral medium, a teller is allowed to say that which one may not vocalize in “polite society.” In other words, oral folktales grant the teller greater freedom of expression than the written word.

Azar even encouraged readers to take ownership of the dialect itself in the stories: apparently, the Ladineros had several debates about the pronunciation and word choice in El Papagyo Djudyo, the subtleties of which could be heard in their performance. Mr. Shemarya, for instance, substituted the word “dumpues” in lieu of the more common “despues.” This is the way he grew up hearing the pronunciation from his mother, Rachel Shemarya, and native of the Island of Rhodes.

The tale of the Jewish Parrot follows Mr. Behar, a wealthy widower from Istanbul, whose friends encourage him to find a new companion to keep him company—a talking Jewish parrot! In the version that Azar first came across, Mr. Behar travels to Paris; since he was in Paris himself, Azar decided to change the scene and had Mr. Behar go to Bloomingdale’s in New York to find the parrot. The Ladineros, in turn, localized the story: in the version they presented at Ladino Day, Mr. Behar goes to Nordstrom right here in Seattle to discover the papagayo djudyo.

Seattle’s long-time Ladino speaking group, Los Ladineros, perform at Ladino Day 2018.

Not only can the parrot speak and not only is he Jewish, but he is also Sephardic, has a wonderful singing voice, and knows all of the Sephardic Jewish liturgy. Once back home in Istanbul, the beguiling parrot both ensures that Mr. Behar diligently recites the kaddish (memorial prayer) for his late wife, and also ropes him into a bet with the synagogue’s cantor: the parrot will sing Ahot Ketana (La Nasyon Djudia), the opening prayer for the service for Rosh HaShana, or else Mr. Behar will owe the sexton thousands of dollars. Unfortunately, Mr. Behar is left embarrassed and disappointed. When the parrot is called up to the mic at the Neve Shalom synagogue in the presence of the famous Hazzan Machorro, he doesn’t even let out a meager squawk.

You’ll have to purchase the book (or watch the video) to see how the story ends, but note here the Ladineros got involved in heavy debate over the concluding lines and its message. They decided therefore to alter the ending to tell a story that reflected more of their own ethos. They also changed many words to accommodate the style of Seattle Ladino.

Illustration in “The Jewish Parrot” by Aude Samama (2014).

As anyone who flips through El Papagayo Djudyo will see, the illustrations are particularly stunning. Creating a visually impressive book was important for Azar. “It’s important to make Ladino glamorous,” Azar said, “so we wanted to use the best artists [for our stories].” Great care also went into portraying real cultural themes and places in Istanbul. Azar showed photographs of the Neve Shalom synagogue and colored postcards from prominent scenes in Istanbul, such as the Kamondo stairs, which provided the basis for the historically inspired illustrations. Mr. Behar himself was modeled on a photograph of Azar’s own grandfather. These are all examples concerning the careful consideration that Azar weighs when presenting Judeo-Spanish in a way that bridges the generations, the past and the present, reality and fantasy.

In addition to Azar’s multigenerational mission, Dr. Naar also highlighted the power of Judeo-Spanish to forge intercultural connections. The uniqueness of Judeo-Spanish comes from the interspersion of words and phrases from the locality in which it was spoken; elements of Turkish, Greek, and other languages are woven together with the Spanish-Hebrew base. To that end, this year’s Ladino Day garnered more support from other departments within the university than ever before.

In the tradition of Ladino Day celebrations of the past, this year’s event served as an important reminder: Just as the name of Azar’s organization Aki Estamos suggests, “we are still here.” But while the early Ladino Day celebrations may have only just confirmed that Judeo-Spanish language and culture is still here in Seattle, this year’s event showed that the culture is also very much alive in other communities across the world. With the continued partnerships between our Seattle Ladino community and others around the world, it is our job to continue to transmit the vibrant language and culture of Judeo-Spanish so that it can be lived by many generations to come.

* Watch the full video of Ladino Day 2018 now *

Special thanks to the Ladineros for their wonderful performance: Regina Amira, Sylvia Azose Angel, Solomon Azose, Al Cordova, Jack Cordova, Al Shemarya, Marlene Souriano-Vinikoor, & Tarin Stefens and Miranda Bumstead (student performers). Hazzan Isaac Azose could not attend but played an instrumental role in leading the rehearsals. PhD candidate Molly Fitzmorris also helped to coordinate the program.

Special thanks to the Lucie Benveniste Kavesh Endowed Fund for Sephardic Studies; Congregation Sephardic Bikur Holim; Congregation Ezra Bessaroth; Seattle Sephardic Network; the Departments of Spanish and Portuguese Studies, French and Italian Studies, and Linguistics; and the Turkish & Ottoman Studies Program in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations for their generous support of this year’s Ladino Day.

Further reading

- “Aki estamos (we are here): Revitalizing Ladino in Paris and beyond” by Molly FitzMorris (2018)

- “Ladino Day Turns to Storytelling — and to the Future” by Hannah Pressman (2018)

- To read more about past Ladino Days, visit our Ladino Day Archive

Makena, such a well written piece you presented to our audience for our 2018 Ladino Day celebration. We are so very proud of you and your many fine accomplishments. Thank you for putting our Ladineros on the map. Many thanks to Professor Devin Naar, of our Sephardic Studies Program, Professor Noam Pianko of our Jewish Studies Program, and all the other sponsoring organizations that made it possible for us to celebrate again in 2018. Special thanks also goes to our wonderful Hazzan Isaac Azose for leading our Ladineros group,but had to be out of town for our presentation this year.

Wonderfully written and accurate account of the evening. You had great insight to the making of the night’s event especially the preparation involved for the reading of the Papagayo Djudyo.

Makena, what a beautiful rendition of Ladino day in Seattle. Unfortunately, due to being out of town, I missed this most important event. While I just happened on this web site, your article help me appreciate the events of that event. Thank you. Ruben Owen

Hi Ruben, thank you for your comment. You can also watch a video recording of the full Ladino Day 2018 program here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fI2XxEEo8N8