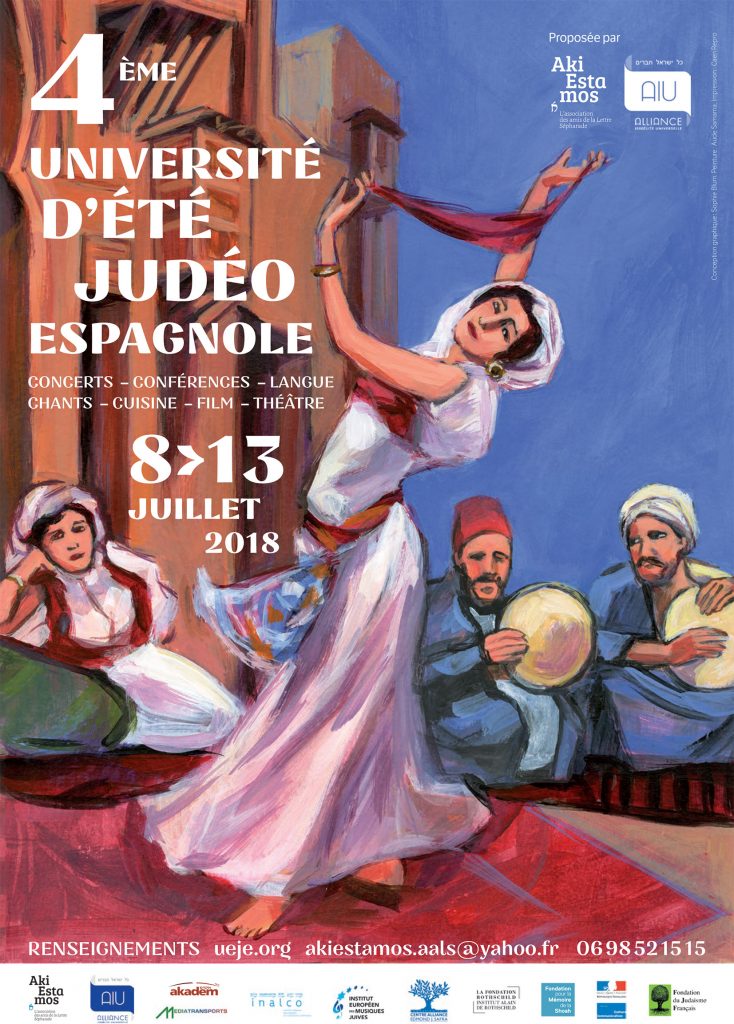

“Universita d’été Judéo Espagnole” (Judeo-Spanish summer university) 2018 poster

By Molly FitzMorris

Aki estamos. We are here.

I hadn’t really thought much about the name of the French Sephardic cultural organization hosting the fourth Universita d’enverano de djudyo (Judeo-Spanish summer “university”) in Paris this summer. But as I looked around the room during president Jenny Laneurie-Fresco’s welcome address, I estimated that there were probably close to 200 people there, and I began to really understand the meaning of the name.

This was truly a one-of-a-kind gathering, an important reminder of the perseverance of the Ladino language and Sephardic culture around the world. You might’ve thought Ladino was dead, yet here we are.

The Universita d’enverano de djudyo is a weeklong enterprise, part academic conference, part summer school, part Sephardic cultural festival. The audience, as far as I could tell, was a mix of academics from around the world, Ladino speakers from various parts of the Ottoman Empire now living in Europe, and Sephardic people who grew up in France hearing Ladino at home but not necessarily speaking it.

From the Ladino play “La vida djudia de ayer a oy en la famiya de Moiz” (“Jewish life from the past until today in Moiz’s family”)

Mid-day academic presentations were sandwiched by morning and afternoon workshop sessions, offering courses in everything from Ladino language and Sephardic culture to Sephardic music to Sephardic cooking. The evenings were filled with Ladino entertainment, including music, a film, and a play!

Yes, there was an hourlong play performed entirely in Ladino, called La vida djudia de ayer a oy en la famiya de Moiz (Jewish life from the past until today in Moiz’s family), performed by three actors from Istanbul. (Check out Dr. Bryan Kirschen’s Twitter account for some video clips of the performance.)

Perhaps my favorite part of the evening entertainment, however, was a concert performed by a group called Kouklaki. Kouklaki is a quintet of Parisian twenty-something musicians who play Balkan, Greek, and Turkish music in the traditional styles. Here’s their rendition of the song “Morenika”:

Though there are plenty of young musicians playing traditional Sephardic music today, I found Kouklaki to be one of the most interesting I’ve heard so far, precisely because they don’t attempt to modernize the music. While I understand the appeal of bringing Sephardic music into the 21st century, I think there’s something special about playing the music as it was played 500 years ago.

“Universita d’été Judeo Espagnole” (Judeo-Spanish summer university) 2018 poster

Another highlight of the Universita was the weeklong pop-up book fair, much like the ones I remember from elementary school. Instead of colorful Scholastic books and the Harry Potter series, however, this book fair comprised a treasure trove of hard-to-find books written about Ladino and Sephardic history and culture. I took the opportunity to snag a copy of Matilda Koen-Sarano’s collection of Sephardic short stories “El kurtijo enkantado” (“The enchanted courtyard”).

If you’re from Seattle, you may be surprised to learn that there are Ladino speakers in France, just as the Ladino speakers at the conference were surprised to learn that there are Ladino speakers in Seattle. You may also be surprised to learn that François Azar, vice president of Aki Estamos and the founder of Lior Press, has co-authored several children’s books in Ladino. You can learn more about these books as well as the wider genre of Sephardic folktales at this year’s Ladino Day celebration in Seattle, to be held on December 5 at 7 PM, where François himself will be the invited speaker.

Toward the beginning of my presentation in Paris, during which I talked about some of the unique and most special aspects of the Seattle varieties of Ladino, I asked, “Vozotros saviash ke ay una komunita ladinoavlante en Siatli (Did you know that there’s a Ladino-speaking community in Seattle)?” I was pretty surprised when most people shook their heads no.

Author Molly FitzMorris (pictured in white dress) with other panelists

Just as I was fascinated by Parisian Ladino that I heard spoken with a French accent, the Parisian Ladino speakers got a kick out of my audio clips, noting that it was spoken with an American accent!

Each time I attend a gathering of Ladino enthusiasts, I’m reminded once again that yes, the Ladino language is very endangered, but there are a lot of people doing important work to help document it, and, in some cases, even revitalize it. In the case of the Universita, though, I had a different experience. Not only did I learn about Ladino and get to hear it constantly for an entire week, but I got to show European Ladino speakers that aki vozotros estash en Siatli — here you are in Seattle!

As we look toward the future of Ladino and work together to document it, it’s important that we continue to make this kind of connection, showing other Ladino speech communities that they’re not in this fight alone, that in fact, aki estamos endjuntos, here we are together.

Leave A Comment