Ty Alhadeff takes a look back at the 4th annual International Ladino Day celebration at the University of Washington, held on November 30, 2016.

Los Ladineros; Ralph Adatto, Marlene Souriano-Vinikoor, Sylvia Angel, Cheryl Lundgrenand and Jack Cordova singing Pasharo D’ermozura.

On November 30, the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and the Sephardic Studies Program hosted its fourth annual International Ladino Day with a screening of Song of the Sephardi followed by a lively panel discussion featuring local community members. Filmed in 1975 by David Raphael, then a student at the University of Washington Medical School, Song of the Sephardi is set in Seattle and Jerusalem. It describes with humor and poignancy the vibrant culture preserved by the local Sephardic community — and poses the existential question: how long will it last?

This lesser-known gem of a film features many local Sephardic community members as actors, including David E. Behar as a mustachioed and bell-bottomed new father at a brit milah, his cousin David Sam Behar as a bachelor on a quest to court a beautiful woman, Rabbi Solomon Maimon — now in his 90s — at one moment explaining the community’s sacred traditions and in the next dancing merrily with a bottle of arak, also known as raki. (Some might say the latter is a sacred tradition, too.)

The audience, as in years past, included native Sephardic community members, their families, as well as members of the Seattle and UW communities at large who take an interest in Sephardic life and the Ladino language. Song of the Sephardi drew laughter and commentary throughout, not just for its humor and 1970s throwback style, but also for the myriad times audience members recognized friends, family, even themselves in the film. Yet for all the humor there was an equal dose of sadness for the many people in the film who have passed on. This observation — that in 40 years the community has aged and lost so many of its central figures — hits home when the film’s focus turns from joyous ritual reenactments to the question of cultural survival.

This was the question taken up by four panelists after the screening of the first half (the Seattle half) of the film. With Professor Devin Naar moderating, Hazzan Isaac Azose, David E. Behar, Judy Amiel, and Makena Owens shared their reflections on the film, the past, and the future of Sephardic life and the Ladino language.

Ladino Day panelists Makena Owens, David E. Behar, Judith Amiel and Hazzan Isaac Azose.

Naar asked the panelists: What is the present status of Sephardic culture in Seattle today? What will it be in the future? Are there more verses to Song of the Sephardi yet to be composed? Each had a unique response, indicative of their experiences and generation. Azose, who grew up in Seattle speaking Ladino and has been instrumental in preserving Ladino here— now in his 80s — is not highly optimistic about the future of Ladino outside of Israel and the university. Held at The Summit, a Jewish retirement home near downtown Seattle, weekly Ladino classes led by Azose that convene a group of two dozen mostly retired Ladino enthusiasts, called Los Ladineros, will continue for as long as possible, he promised. But for Azose, Song of the Sephardi seemed to remind him of the many Sephardic community members who are no longer with us.

Amiel, the daughter of Reverend Samuel Benaroya who was instrumental in transmitting Sephardic liturgy to the next generations in Seattle, likewise experienced some level of grief at what has been lost with the passing of the first generation of Seattle Sephardim. She admits that her children and grandchildren will not carry on the Ladino language in a deep way, even though they do frequently ask her how to translate English words into Ladino and sprinkle certain Ladino words into their everyday English. Amiel realizes that this is something her generation needs to take responsibility for. “We need to tell them more,” she said.

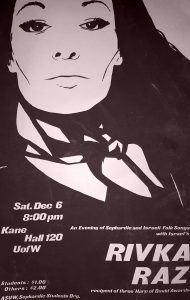

Advertisement for Rivka Raz’s concert at the University of Washington from the Jewish Transcript, December 6, 1975.

It may be understandable that Azose and Amiel watched Song of the Sephardi with a sense of loss. One could say, after watching these celluloid memories, that the golden age of Ladino and Sephardic life in Seattle has passed–and was already on its way out in the 1970s.

But David Behar and Makena Owens weren’t going there. Behar pointed out a moment in the film that could have easily been missed: a crowd of young people pouring into a theater to hear the well-known Ladino singer Rivka Raz from Israel. That event was organized by a short-lived Sephardic student organization in the 1970s. Although that organization did not continue, 40 years later, Behar sees the university reclaiming a leading role in perpetuating Sephardic culture. Incidentally, the Rivka Raz concert took place in the same university building and room as Ladino Day– Kane Hall 120. Talk about coming full circle.

Owens, the youngest member of the panel, graduated from Northwest Yeshiva High School and is working toward a master’s degree in Jewish Studies at Yeshiva University. Makena followed in the footsteps of her grandmother, Lela Abravanel, a native of Salonika, who performed at the first two Ladino Day celebrations, treating the audience to her collection of Ladino refranes (sayings). Makena grew up hearing her grandparents speak Ladino and became more involved in the study of the language while in college. In 2014, Makena won the Monis and Chaya Zuckerman Memorial Award for best research paper in Jewish history at Stern College based on her independent study with Professor Naar of two Viennese Ladino prayer books from the Sephardic Studies Collection at the UW.

Makena is proud to be a Sephardi Seattle Jew. Among her friends in New York — especially other Sephardic and Mizrachi Jews — she takes special pride in her heritage that links her to the Ottoman Empire and to the Ladino language. “We have an amazing love and appreciation for the type of Sephardic Jews that we are,” she said.

Makena is optimistic about the future of Ladino. Song of the Sephardi inspired her, given how much of the culture has been retained rather than lost. Many of the traditions in the synagogue are still familiar to her. “What has been really important,” she said, “has been to legitimize the language in an academic context. For me that has been a really good way to get me more interested in learning the language and understanding the importance of the language, because when it’s brought to the forefront, like in a university setting, it really gets people to pay attention and say, ‘Oh my God, this is something that is really at the heart of Sephardic culture and Sephardic Judaism and we need to preserve it so that it doesn’t get lost.’”

David Behar shared this optimistic sentiment, too. He emphasized that “ensuring the future of Sephardic culture in Seattle will not be achieved by trying to replicate or preserve our past in form. The continuity and future of Sephardic culture is more a function of understanding and perpetuating the substance of who we are as a community. The cultural treasures we possess transcend ethnicity, folklore, customs, food and language and, in fact, are an essential part of the fabric of Judaism, in general. Though beautiful and critically important, these all constitute the beautiful package in which our culture, philosophy and spiritual tradition reside — but not their essence.”

Behar also pointed out that he never would have imagined, when he headed that Sephardic student group in the 1970s, that one day the UW would have a Professor Naar and a Sephardic Studies Program. “We never would have dreamed in 1975 that would be a reality. It’s amazing,” he said. “We never would have dreamed that Hazzan Azose and Joel Benoliel would have produced, probably for the first time since the early 20th century, an Ottoman Ladino traditional set of prayer books, for daily, Sabbath, for all of the holidays….There has been significant assimilation, there have been some significant losses, but on the other hand we’ve got some real strength.”

A scene from the film of members of Sephardic Bikur Holim studying Sefer Me-am-Lo’ez with Rabbi Solomon Maimon.

For me, the most inspirational moment was knowing that all of the copies of the Me’am Loez, one of the most famous works of Ladino literature and featured in the movie, are now digitized in the Sephardic Studies Collection. It is satisfying to know that almost every Ladino liturgical tradition mentioned by Rabbi Maimon in this film, have been explored in our Sephardic Treasures articles, including Ketubah De La Ley, the Haftara for Tisha Be-Av, the Passover Haggadah, Koplas de Purim, and the High Holiday liturgical poems. Our efforts to preserve these Ladino texts continue: even on this year’s Ladino Day we received new Sephardic artifacts including audio, visual, and textual materials from three members of the audience.

Looking toward the future, Professor Naar talked about his own efforts to reclaim the language at home by singing and speaking to his one-year son in Ladino. He expressed his personal gratitude to Seattle’s Los Ladineros for their efforts to create new Ladino literature for children by completing their first work “La Ijika Kon La Kapeleta Kolarada,” a translation of “Little Red Riding Hood.”

UW President Ana Mari Cauce reading the mayor’s proclamation recognizing International Ladino Day in Seattle, 2013.

The evening concluded, of course, with two lively songs led by Los Ladineros followed by a warm social gathering surrounded by Sephardic delicacies. Much Sephardic culture may be behind us, but if this fourth successful Ladino Day is any indication, we’re just getting started.

This event was made possible by the generous support of the Lucie Benveniste Kavesh Endowed Fund for Sephardic Studies and co-sponsored by The Seattle Sephardic Network, Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation, and The Seattle Sephardic Brotherhood.

Special thanks to Emily Thompson for helping to organize the 2016 International Ladino Day celebration. Additional thanks to all of the members of Los Ladineros; Marcelle Adatto, Ralph Adatto, Vivian Adatto, Regina Amira, Vic Amira, Sylvia Angel, Luis Antezana, Hazzan Ike Azose, Jack Cordova, Lilly DeJaen, Menache Israel, Cheryl Lundgren, Al Shemarya and Marlene Souriano-Vinikoor.

Leave A Comment